Reefer Madness – 1895 to the Present – Chapter 2: Pre-1895 Demonization and Stigmatization

In this chapter, DML explores the demonization and stigmatization of cannabis from ancient times through the modern era – before that stigmatization took on a visual element.

Special thanks to the Cannabis Museum for sponsoring the creation of this series. The introduction to this series (Reefer Madness – 1895 to the Present) can be found here. Chapter 1 can be found here.

“Thus no devil’s weed will be found among you . . .”

– Ignatius, third Bishop of Antioch, To the Ephesians, circa 107–110 CE

(Cyril C. Richardson 1953 translation) (1)

“. . . that no herb of the devil be found in you . . .”

-Ignatius, third Bishop of Antioch, To the Ephesians, circa 107–110 CE

(Lightfoot & Harmer, 1891 translation) (2)

“Other alleged effects of the drugs have attracted but little attention compared with their alleged connection with insanity.”

– Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Vol. 1, p. 225 (3)

“’Cause slavery was abolished, unless you are in prison.

You think I am bullshittin’ then read the 13th Amendment.

Involuntary servitude and slavery it prohibits.

That’s why they givin’ drug offenders time in double digits.”

Reagan, Killer Mike, R.A.P. Music, 2012

What’s so special about the year 1895? As far as this author can prove, that’s the year that “cannabis-related psychosis” or similar demonization/stigmatization was first depicted in images rather than simply in text. The context that accompanied these images implied that this psychosis was the inevitable result of proper cannabis use, not merely a possible result of cannabis abuse.

These images (which began with newspapers, then which moved to films, magazines, book covers, government-issued pamphlets and comic books) were meant to encourage fear and hatred of the scapegoat. 1895 was when the smear campaign became a full-on genocidal-in-scope (4) propaganda war, designed to eliminate herbal medical autonomy by justifying laws written with the expressed purpose of destroying the entire cannabis using/growing/distributing community.

Sure, cannabis can cause acute short-term psychosis when used improperly and/or immoderately, and perhaps can trigger long-term psychosis in people already genetically predisposed to it, but it can also be an effective treatment for psychosis, especially once the myth of “inherent harm” is challenged and debunked, proper dosing and smoking techniques become common knowledge and research into CBD as a treatment for psychosis is maximized.

If you happen to believe, as I do, that 1) cannabis can be used properly and to the benefit of the vast majority of users and that 2) the persecution of cannabis users is 100% to do with scapegoating to facilitate white supremacism, corporate monopolies and police and army protection rackets and 0% to do with genuine concerns over health, then it follows that the demonization/stigmatization of cannabis can never be seen as justified.

The history of this demonization/stigmatization should be seen in its proper context: cannabis prohibition is and always has been an unfair attack – for the sake of power and greed – upon a maligned group of scapegoats, who’s supposed “crime” is actually acting on their intelligent preference for one of the cheapest, safest and most effective herbal medicines in human history.

The demonization or stigmatization of cannabis reveals a couple of things about the person doing the demonizing/stigmatizing. Firstly, it reveals an ignorance – often a wilful ignorance – about the different effects of cannabis that come with different dose levels. Secondly, it reveals a desire upon the part of the scapegoater to foist derision upon their victims rather than attempt to understand them. Then, as now, the scapegoater, in their attempt to expose the innate defects of their targets, merely reveals their own flaws.

It’s instructive, then, if one were to want to challenge the narrative and help bring an end the scapegoating, not only to catalogue all the best examples of images used in the pursuit of the scapegoating of cannabis users (and growers and dealers) and put them in chronological order, which is what most of this book is about, but also to conduct an overview of the history of non-image-based but rather text-based pot-user/distributor scapegoating – the context that led up to that point: 1895 – which is what this chapter is about.

The cartelization of the cannabis economy began in India. Ancient Aryan Invaders of India kept the knowledge of the sacramental use of cannabis to themselves by limiting the number of people who could had access to – and who had the ability to read – their holy books – which contained their cannabis-based sacrament recipes. Researchers of ancient cannabis history noted that;

“Eventually the indigenous priestly elite usurped much of the religious authority held by the writers of the Aryan hymnal and gained control of the theological interpretation and ritual. . . . Apparently for some time members of the priestly clique limited the knowledge and use of Soma to their own esoteric activities. Thus a small influential segment of ancient Indian society controlled religion and the distribution of the Soma plant.” (5)

Image #1: Soma Priest. “Reciting Brahman, VEDIC PERIOD (1500–500 B.C.): ARYANS, EARLY HINDUISM AND CASTES, LIFE AND GOVERNMENT” https://factsanddetails.com/India/History/sub7_1a/entry-4102.html

Image #1: Soma Priest. “Reciting Brahman, VEDIC PERIOD (1500–500 B.C.): ARYANS, EARLY HINDUISM AND CASTES, LIFE AND GOVERNMENT” https://factsanddetails.com/India/History/sub7_1a/entry-4102.html

Similarly, the early Hebrew leadership – beginning with Moses – would keep access to the recipes for their holy “kaneh-bosm” (cannabis) anointing oil (found in Exodus 30:23) limited to those who could read: prophets, priests and kings. Anyone aside from these people who used this holy oil were (according to Exodus 30:33) to be banished – “cut off from their people” – to roam the dessert alone and die of exposure to the elements or be mugged, killed or enslaved by bandits – a literal death sentence for attempting to circumvent the cannabis cartel. (6)

Image #2: Kanehbosm Priest. “Priestly Duties (1695 woodcut by Johann Christoph Weigel)” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vayikra_%28parashah%29#/media/File:Priestly_Duties.gif

Image #2: Kanehbosm Priest. “Priestly Duties (1695 woodcut by Johann Christoph Weigel)” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vayikra_%28parashah%29#/media/File:Priestly_Duties.gif

Image #3: Kanehbosm in Exodus. The Living Torah, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, Maznaim Publishing Corporation, New York, 1981, p. 442. Image taken from “Cannabis or Kaneh-Bosm in the Bible,” 2 MAR 2013 https://civilizationorbarbarism.com/2013/03/02/cannabis-or-kaneh-bolsem-in-the-bible/

Image #3: Kanehbosm in Exodus. The Living Torah, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, Maznaim Publishing Corporation, New York, 1981, p. 442. Image taken from “Cannabis or Kaneh-Bosm in the Bible,” 2 MAR 2013 https://civilizationorbarbarism.com/2013/03/02/cannabis-or-kaneh-bolsem-in-the-bible/

In spite of this prohibition, Jewish women continued to worship Asherah – God’s wife back in early Judaism – and used the forbidden cannabis incense and anointing oil as sacraments in their worship:

“The ritual of using cannabis in religious rites continued, especially within the Ashera cults of the pre-Reformation temples in Jerusalem, ‘who anointed their skin with it (cannabis resins and other aromatics), as well as burned it.’” (7)

Image #4: Asherah. https://i.pinimg.com/originals/24/0f/54/240f546ff08ae87f9fb789d0d1036cc5.jpg

Image #4: Asherah. https://i.pinimg.com/originals/24/0f/54/240f546ff08ae87f9fb789d0d1036cc5.jpg

Image #5: Baal & Asherah. http://answersingenesis.org/archaeology/does-archaeology-support-the-bible/

Image #5: Baal & Asherah. http://answersingenesis.org/archaeology/does-archaeology-support-the-bible/

Image #6: King Solomon Worshipping Asherah. Kings & Prophets In The Promised Land, Jaca Books, Le Centurion, 1983

Image #6: King Solomon Worshipping Asherah. Kings & Prophets In The Promised Land, Jaca Books, Le Centurion, 1983

The Asherah cult came under attack by a boy King named Josiah – the first prohibitionist with zeal;

“. . . in the 12th regnal year he commenced to suppress idolatry and other unlawful worship, a work that he prosecuted for years, not only in Judah and Jerusalem, but after his 18th year in Israel also. . . . After the king and his subjects had together covenanted to worship Yahweh only, they proceeded to take the vessels of Baal, of Asherah, and of the heavenly bodies, burn them . . . Nor did he scruple to slay the living idolatrous priests themselves . . .” (8)

Arguably, this attempt by King Josiah at the cartelization and consolidation of the economy and power of religion was where the first two commandments – the “Thou shalt have no other gods before me “ and the “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image” commandments – came from. (9)

Image #7: Josiah Discovers Commandments. The Illustrated Family Bible, Peter Dennis & Dorling Kindersley, 1997

Image #7: Josiah Discovers Commandments. The Illustrated Family Bible, Peter Dennis & Dorling Kindersley, 1997

Image #8: Asherah Prohibition. “Weeks 7 & 8 – Son of David – I and II Kings,” Women Journeying Through The Bible . . . https://wjttb-womenofthebible.weebly.com/blog/weeks-7-8-son-of-david-i-and-ii-kings

Image #8: Asherah Prohibition. “Weeks 7 & 8 – Son of David – I and II Kings,” Women Journeying Through The Bible . . . https://wjttb-womenofthebible.weebly.com/blog/weeks-7-8-son-of-david-i-and-ii-kings

Image #9: Asherah Prohibition. Image taken from The Illustrated Family Bible, Peter Dennis & Dorling Kindersley, 1997

Image #9: Asherah Prohibition. Image taken from The Illustrated Family Bible, Peter Dennis & Dorling Kindersley, 1997

Aside from Moses, another famous ancient pot dealer was Jesus Christ. The Romans may have attempted to murder Jesus for his kaneh-bosm distribution network for the same reason King Josiah murdered the worshipers of Asherah – to consolidate religious power and the sacrament economy into the hands of the few and the associates of the state.

Image #10: Jesus With Anointing Oil. “One of the oldest representations of Jesus as the Good Shepherd, made around 300 AD.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Good_shepherd_02b_close.jpg

Image #10: Jesus With Anointing Oil. “One of the oldest representations of Jesus as the Good Shepherd, made around 300 AD.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Good_shepherd_02b_close.jpg

The Greek word “Christ” and the Hebrew word “Messiah” mean the same thing – “the anointed one.” Anointed, as in drenched in “kaneh-bosm” holy anointing oil. (10) It’s quite possible that one of the things that got the Jewish religious hierarchy so angry at Jesus Christ was that (according to Mark 6:13) he distributed this holy anointing oil to anyone who was sick (11) – he cast out demons (or those who were epileptic), healed the blind (or those with glaucoma) and healed the lepers (or those with pruritus). All three of these conditions are treated with cannabis, as the evidence demonstrates. (12) Jesus also said “It’s not what goes into your mouth that defiles you; you are defiled by the words that come out of your mouth.” (13) In other words, don’t judge a person by their diet or medicinal choices – judge them by how they treat other people.

Christ’s message of dietary and medical autonomy was lost on his early worshippers. An “early church father” – Ignatius (circa 35-107 CE)– put it plainly in his instructions to heads of the Roman Universal (Catholic) Church:

“Return their violence with mildness and do not be intent on getting your own back. By our patience let us show we are their brothers, intent on imitating the Lord, seeing which of us can be the more wronged, robbed, and despised. Thus no devil’s weed will be found among you; but thoroughly pure and self-controlled, you will remain body and soul united to Jesus Christ. . . . At these meetings you should heed the bishop and presbytery attentively, and break one loaf, which is the medicine of immortality, and the antidote which wards off death but yields continuous life in union with Jesus Christ.” (14)

In case you didn’t catch the above scam, leading ancient cannabis historian/author Chris Bennett explained it in plain English:

“The words of the early church father Ignatius, show distinctly the substitution of the placebo sacraments of the Catholic Church, in place of the Gnostic entheogens, setting the stage for drug war hysteria that has lasted into our present day.” (15)

As early as Irenaeus, (130-200 CE), accusations concerning “secret sacraments” began being leveled at Gnostic branches from the Roman Church. (16) Around 325 CE, Constantine – the first Christian Roman emperor – began to confiscate or destroy the property of less dogmatic sects as Jesus predicted the scribes would do. Many temples (and priests) were destroyed. (17) Another emperor – Theodosius (379-395) – decreed that all sacrifice (wine and incense) to idols were treasonous – crimes against the state – punishable by death. (18) Some people say the “Dark Ages” began soon after this (19) – a time when ignorance was dominant and enlightenment scarce – a time that would last at least until Europeans began to make paper in the middle of the 1000s, or until paper spread to all of Europe by the early 1600s and to America by the late 1600s. (20)

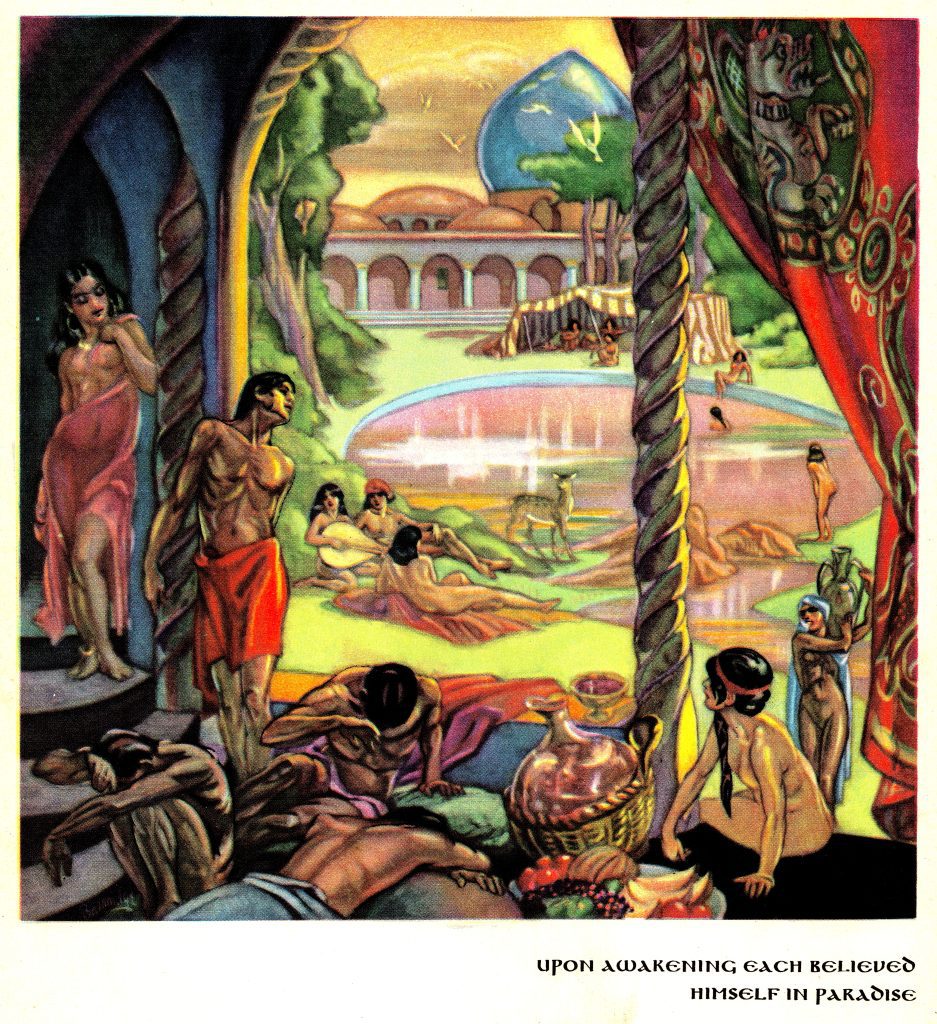

At or around the year 1300, The Travels of Marco Polo was first published. It was an autobiographical book dictated to Rustichello da Pisa, Polo’s fellow inmate in a Genovesian jail. The book contains a very famous passage regarding the origin of the term “assassin” being viewed as a derivation of the term “hashish eater” – the origin of the story how “The Old Man Of The Mountain” would use hashish to indoctrinate young recruits to his assassination squad;

“Then he would introduce them into his garden, some four, or six, or ten at a time, having first made them drink a certain potion which cast them into a deep sleep, and then causing them to be lifted and carried in. So when they awoke, they found themselves in the Garden.” (21)

Image #11: Marco Polo’s Assassins. Image taken from “The Assassins,” National Geographic’s Secret Societies, 2017, p. 48

Image #11: Marco Polo’s Assassins. Image taken from “The Assassins,” National Geographic’s Secret Societies, 2017, p. 48

Image #12: “Upon awakening each believed himself in paradise”, The Adventures of Marco Polo, Edited by Richard J. Walsh, Illustrated by Cyrus Le Roy Baldridge, John Day Company, New York, 1948, p. 49

The recruit would then be given “ladies and damsels” that would dally with them “to their hearts content, so that they would have what young men would have, . . .” Over the last 150 years, the story was sometimes repeated accurately (22), but was often told in such a way as to suggest that hashish was used to enrage or hypnotize the recruits or poison the targets of the assassins rather than as a non-toxic knock-out drug used to aid in creating the illusion of a pleasure-filled, accessible afterlife. There is some debate in the last few decades as to whether this Ismaili sect even used hashish or if it was simply a disparaging rumour that was started by their enemies, but the recent scholarship of Chris Bennett outlines the plethora of evidence that hashish was used extensively by this branch of the Ismaili religion. (23)

In the middle-ages, occult magic books (grimoires) such as the Picatrix (13th century) (24), The Book of Oberon (16th century) (25), and Sepher Raziel: Liber Salomonis (16th century) (26) were associated with the use of cannabis in the form of incense and ointments. Also associated with cannabis was the worship of Pan/Puck/Robin Goodfellow/Green Man horned god/fairy, worshipped by witches. (27)

Image #13: Gustave Doré, La Dance Du Sabbath, Hemp Field In Background. Image originally from History of Magic by Paul Christian, Paris, 1870. Image taken from Plants Of The Gods, Richard Evans Schultes & Albert Hofmann, Inner Traditions, Rochester, Vermont, 1992, p. 91

Image #13: Gustave Doré, La Dance Du Sabbath, Hemp Field In Background. Image originally from History of Magic by Paul Christian, Paris, 1870. Image taken from Plants Of The Gods, Richard Evans Schultes & Albert Hofmann, Inner Traditions, Rochester, Vermont, 1992, p. 91

According to Chris Bennett, “. . . we can be sure that the combination of magic books and preparations would have been enough to alarm the authorities and sentence the persecuted.” (28) Bennett quotes author Aaron Leitch, who writes “The inquisition was founded to ferret out heresy ‘from within’ the Church. They only turned to common midwifes and healers after they ran out of fellow priests to hang.” (29)

There was so much demonization of herbal medicine at this time that even as late as the 1500s and 1600s writers such as the French Dr. and humorist Francois Rabelais (30) and English playwright William Shakespeare (31) both had to limit themselves to hinting at the inspirational and performance-enhancing effects of cannabis in their work rather than be up-front about it, for fear of being labeled a witch, wizard or sorcerer and put to death as punishment.

The scientific revolution brought with it a more rational approach to healing – that healing involves biochemistry rather than magic, God and the devil. The scientific revolution also brought with it a more sophisticated form of scapegoating. Instead of demonization, it became all about stigmatization. Instead of cannabis making you worship harmful gods or even Satan himself, it made you murderously insane.

But not at first. As the superstition that allowed for the witch-hunts waned and myth was replaced with science and reason, certain prominent scientists lent their names to cannabis medicine within the context of the re-emerging herbal healthcare system that the scientific era brought with it. As it turns out, many of them were getting their hands on some potent cannabis indica. “Indica” is a classical Greek and Latin term for “of India” and – unlike cannabis sativa, which could be either industrial or medicinal – is exclusively a medicinal cultivar.

In 1689 an account of the plant from India called Bangue, (an Indian term for cannabis) at that time largely unfamiliar to the British, was presented before the Royal Society by Dr. Robert Hooke (1635–1703) – a pioneer of science, called by some “England’s Leonardo.” Descriptions of the effects upon ingesting a dose included “. . . yet is he very merry, and laughs, and sings.” (32)

Linnaeus (1707-1778), the father of modern taxonomy, stated that cannabis could be used for “chasing away melancholy” making the user feel “happy and funny.” (33) The 1722 English herbal by Joseph Miller mentions cannabis use as an aphrodisiac, saying “. . . the famous Bangue, so much used by the Persians and Indians to promote Venery, is a Species of Hemp.” (34)

On August 7th, 1765, George Washington wrote in his diary that he “began to separate the Male from the Female hemp at Do. – rather too late.” (35) Some have argued this indicates Washington was attempting to grow sinsemilla – “without seed” – in other words, more potent buds. (36) There is additional evidence that Washington was growing hemp for the resin. On January 6th, 1794, Washington wrote in a letter to “Howell Lewis or William Pearce” (his farm managers):

“I also gave the Gardener a few Seed of East India hemp to raise from, enquire for the seed which has been saved, and make the most of it at the proper Season for Sowing.” (37)

Later that same year, on August 17th, 1794, Washington wrote to William Pearce that

“I cannot with certainty recollect, whether I saw the India hemp growing when I was last at Mount Vernon; but think it was in the Vineyard; somewhere I hope it was sown, and therefore desire that the Seed may be saved in due season & with as little loss as possible: that, if it be valuable, I may make the most of it.” (38)

From these quotes in can be argued that Washington began by growing sinsemilla and ended up growing cannabis indica in his vineyard (with his other valuable drug crop, not out in the regular field with his food crops) and that he repeatedly stressed to his farm managers that he wanted to make the most of it. Cannabis indica is the drug cultivar. Washington wasn’t just growing hemp (as most people believe) – he was growing marijuana.

At the start of the 1800s, reports about “Bangue” or “bang” (which could refer to a drink containing cannabis, or an extract of cannabis, or the plant itself) continued to be generally positive. In a May, 1811 article in the London magazine Quarterly Review, a traveller’s tale entitled “Kirkpatrick’s Account of the Kingdom of Nepaul” (sic), the author describes the diet and medicine of the locals;

“Animal food and spirituous liquors are prohibited; but in lieu of the latter, the cherris, an extract from the common hemp, known in India by the name of bang, is resorted to for producing a species of calm illusion devoid of care, and unmixed with the irritation and subsequent languor which results from the use of opium, wine or spirits. From all these the Brahmin religiously abstains; but he has no scruple to take the ‘sweet oblivious antidote’ which the flower buds and leaflets of the cannabis sativa are capable of affording, when bruised and put into a little milk.” (39)

It wasn’t until later in the 1800s that hashish began to be mentioned in newspapers. And this was where the stigmatization began. One of the earliest mentions of hashish in the press occurred in Ireland: on page 4 of the September 15th, 1837 Belfast News-Letter. Somehow the knock-out drug of Marco Polo became a deadly poison in this story’s latest incarnation:

“One of the most remarkable words, as far as origin is concerned, in the English tongue, is assassin. In the era of the crusades, this term was introduced into the languages of Europe, being derived from a tribe of murderous fanatics, who infested Asia for several centuries, and who were under the command of a chief, commonly styled the Old Man of the Mountain. To this chief, his followers, deceived into the hope of thereby gaining paradise, paid implicit obedience, recklessly sacrificing their own lives in the execution of his orders, which were almost uniformly death warrants. This terrible sect, according to some authors, derived their appellation of assassins from Hassan their founder, and according to others, from hashish a narcotic herb, which they sometimes substituted for the dagger, in compassing the destruction of their victims. More than one of the crusading princes fell beneath the far-extended arm of the old monster of the mountain – for man such a being merits not to be called. And this is the worthy source of our synonyme for a secret murderer.” (40)

The same article was reprinted in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle seven years later (41) For many, this mis-telling of the Marco Polo story was their first introduction to cannabis medicine – hashish, a supposed substitute for a dagger.

On February 4th 1843, the true scientific, systematic study of cannabis as a medicine began with an article written by Dr. William Brooke O’Shaughnessy in the Provincial Medical Journal of London. O’Shaughnessy worked in Calcutta, India from 1833 to 1841 and had the occasion to experiment with “gunjah” on both animals and people. He limited his human experiments to those subjects with physical ailments rather than mental ones, but noted that smaller doses worked better than bigger, and that excessive pot use wasn’t as bad as excessive use of other drugs:

“There was sufficient to show that hemp possesses, in small doses, an extraordinary power of stimulating the digestive organs, exciting the cerebral system, of acting also on the generative apparatus. Larger doses, again, were shown by the historical statements to induce insensibility or to act as a powerful sedative. The influence of the drug in allaying pain was equally manifest in all the memoirs referred to. As to the evil sequelae so unanimously dwelt on by all writers, these did not appear to me so numerous, so immediate, or so formidable, as many which may be clearly traced to over-indulgence in other powerful stimulants or narcotics – viz, alcohol, opium or tobacco.” (42)

Image #14: O’Shaughnessy, W.B. (1843). “On the preparations of the Indian hemp, or Gunjah, (Cannabis Indica),” Prov Med J Retrosp Med Sci. 5 (123): p. 1

Image #14: O’Shaughnessy, W.B. (1843). “On the preparations of the Indian hemp, or Gunjah, (Cannabis Indica),” Prov Med J Retrosp Med Sci. 5 (123): p. 1

Regarding the “evil sequelae” – sequelae being “a condition which is the consequence of a previous disease or injury” – O’Shaughnessy was referring to the stigma being foisted upon gunjah medicine at the time by Europeans, which must have been universal, given his description of it being “unanimously dwelt on by all writers.” O’Shaughnessy found that a half-grain (33 milligrams) of hashish was all that was needed for a therapeutic dose, without any ill effects:

“In several cases of acute and chronic rheumatism admitted about this time, half-grain doses of the resin were given, with closely analogous effects; alleviation of pain in most, remarkable increase of appetite in all, unequivocal aphrodisia, and a great mental cheerfulness. In no one case did these effects proceed to delirium, or was there any tendency to quarrelling.” (43)

In 1844, the Club des Hashischins formed in Paris, and was active for the next five years. Some of the greatest artists, writers, poets and scientists in Paris at the time were active in the club. (44) Club members experimented with “dawamesk” – “a greenish paste made from cannabis resin mixed with fat, honey, and pistachios.” (45)

Because club members ate their hashish instead of smoking it, and because they were engaged in unstructured experimentation rather than engaging in careful minimum-dose incremental increases, they inevitably suffered from overdose, and some members associated all use with feeling ill or unpleasant. In his book Charles Baudelaire: His Life by club member Theophile Gautier (regarding another club member, Charles Baudelaire), their brief flirtation with hashish edibles was dismissed as experimenting with an unnecessary poison:

“After some ten experiments we renounced once and for all this intoxicating drug, not only because it made us ill physically, but also because the true littérateur has need only of natural dreams, and he does not wish his thoughts to be influenced by any outside agency.” (46)

Baudelaire recorded his overdoses in his book Les Paradis Artificiels, with similar ignorant dismissals. (47)

Image #15: 1844. “A self-portrait by Charles Baudelaire made under the influence of hashish.” High Society, Mike Jay, Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont, 2010, p. 89

Image #15: 1844. “A self-portrait by Charles Baudelaire made under the influence of hashish.” High Society, Mike Jay, Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont, 2010, p. 89

Image #16: Portrait of Charles Baudelaire, 1844, by Emile Deroy https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Charles_Baudelaire

Image #16: Portrait of Charles Baudelaire, 1844, by Emile Deroy https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Charles_Baudelaire

One bit of wisdom that did result from their experimentation was the importance of setting to the quality of the experience. Gautier made careful note of that:

“It is understood, then, if one wishes to enjoy to the full the magic of hashish, it is necessary to prepare in advance and furnish in some way the motif to its extravagant variations and disorderly fantasies. It is important to be in a tranquil frame of mind and body, to have on this day neither anxiety, duty, nor fixed time, and to find oneself in such an apartment as Baudelaire and Edgar Poe loved, a room furnished with poetical comfort, bizarre luxury, and mysterious elegance; a private and hidden retreat which seems to await the beloved, the ideal feminine face that Chateaubriand, in his noble language, calls the ‘sylphide.’ In such circumstances, it is probable, and even almost certain, that the naturally agreeable sensations turn into ravishing blessings, ecstasies, ineffable pleasure, much superior to the coarse joys promised to the faithful in the paradise of Mahomet, too easily comparable to a seraglio. The green, red, and white houris coming out from the hollow pearl that they inhabit and offering themselves to the faithful, would appear as vulgar women compared to the nymphs, angels, sylphides, perfumed vapours, ideal transparencies, forms of blue and rose let loose on the disc of the sun and coming from the depths of infinity with stellary transports, like the silver globules on gaseous liquor, from the bottom of the crystal chalice, that the hashish-eater sees in innumerable legions in the dreams he dreams while wide-awake. Without these precautions the ecstasy is likely to turn into-nightmare. Pleasure changes to suffering, joy to terror; a terrible anguish seizes one by the heart and breaks one with its fantastically enormous weight, as though the sphinx of the pyramids, or the elephant of the king of Siam, had amused itself by flattening one out. At other times an icy cold is felt making the victim seem like marble up to the hips, like the king in the ‘Thousand and One Nights,’ half changed to a statue, whose wicked wife came every morning to beat the still supple shoulders.” (48)

In 1845, another member of the Club des Hashischins – Dr. J.J. Moreau Du Tours – published his pivotal book Du haschisch et de l’aliénation mentale: études psychologiques, republished in English in 1973 as “Hashish and Mental Illness.” In it, Dr. Moreau (who only took hashish orally and never smoked it) discussed hashish leading to “irresistible impulses” “if the toxic action is very strong” (49) – in other words, too strong a dose has a negative effect on good decision-making. He also saw therapeutic potential;

“One of the effects of hashish that struck me most forcibly and which generally gets the most attention is that manic excitement always accompanied by a feeling of gaiety and joy inconceivable to those who have not experienced it. I saw in it a means of effectively combatting the fixed ideas of depressives, of disrupting the chain of their ideas, of unfocusing their attention on such and such a subject. It was perhaps no less appropriate to arouse the drowsy intelligence of mute (stupides) psychotics or even to return a little energy and resiliency to the demented.” (50)

Image #17: 1845 Du Hachisch Et De L’Alienation Mentale, Etudes Psychologiques, Par J. Moreau (De Tours), Paris, Librarie De Fortin, Masson Et Cie, 1845

Image #17: 1845 Du Hachisch Et De L’Alienation Mentale, Etudes Psychologiques, Par J. Moreau (De Tours), Paris, Librarie De Fortin, Masson Et Cie, 1845

The problem doctors of this period had with hashish was that most if not all of them were unable to identify the advantages of smoked hashish over orally-ingested hashish: smoking resulted in rapid onset of effects (30 seconds to 3 minutes), and allowed for titration – fine tuning the dose (51) – in ways that were (and still are) impossible for oral ingestion.

Properly determining the right dose for a person a) can depend upon the highly individual built-in sensitivities or tolerances of the user, and b) can be difficult, as all too often the effects take at least 30 (and up to 120 minutes) to manifest. Accurate ideal dosing with edible cannabis products involves either luck or days of incremental increases in dose until the desired effects were achieved with a minimum of the negative effects which would invariably accompany an overdose. Titration is an art familiar to few, especially in the 1800s.

In a novel titled La Comtesse de Charny (The Countess De Charny in English), published in 1855 and first published in English in 1867, Alexandre Dumas (another member of the Club des Hashischins) tells the story of the death of the Count of Mirabeau, a noble and participant in the French Revolution. On his deathbed, his doctor gave him a tincture of hashish, which had “. . . given the invalid, with speech, the play of his muscles . . .”. (52)

Image #18: Fitz Hugh Ludlow, a pioneer of cannabis destigmatization in the United States. Author of The Hasheesh Eater, 1857. Image from https://alchetron.com/Fitz-Hugh-Ludlow

Image #18: Fitz Hugh Ludlow, a pioneer of cannabis destigmatization in the United States. Author of The Hasheesh Eater, 1857. Image from https://alchetron.com/Fitz-Hugh-Ludlow

Britain had ruled and exploited much of India for nearly two centuries – first through the East India Company (1757-1858) and then directly (1858-1947). To rationalize doing so, a lot of white supremacist/racist justifications were utilized, including attitudes towards Indian subjects who suffered from various mental health issues. A close analysis of the treatment of cannabis users in British insane asylums reveals how a combination of racism and a lazy approach to diagnosis gave rise to their blaming insanity on cannabis use;

“In 1871 a superintendent voiced his concern that ‘causation is, as usual, very unsatisfactorily noted among the admissions. Antecedent information is commonly difficult to procure. Intemperance is an assigned cause in 9 cases, but with one or two exceptions I doubt whether it can be regarded as in any sense a true cause in this number.’” (53)

One British doctor admitted in 1872, that;

“. . . an attempt has been made this year to distinguish between those cases of insanity clearly due to ganjah-smoking and those in which the use of ganjah has only been occasional, and therefore insufficient to excite insanity. The attempt has not been successful. For want of any other reason, it has been necessary to enter under the heading of ganja several who were merely reported to have indulged in its use.” (54)

In 1872, the Kentucky Legislature passed a law for the management of the estate and personal confinement of any person who “has, by the habitual or excessive use of opium, arsenic, hasheesh, or any drug, become incompetent to manage themselves or estates with ordinary prudence and discretion.” (55)

In 1878, a more accurate assessment of the effects of eating hashish were recorded in The Popular Science Monthly. The assessment was written by Dr. Charles Richet, a brilliant French physician who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in medicine for his work on anaphylaxis, but who did not possess the intellect or wisdom necessary to avoid being a racist eugenicist. (56) His initial analysis of the effects of cannabis was accurate enough:

“Taken in moderate doses, it produces a kind of intoxication that is very pleasant, highly advantageous for a correct knowledge of intellectual phenomena, and at the same time free from serious consequences.” (57)

Richet obviously ate hashish himself, as his assessment of the effects of the drug were filled with the detail of someone speaking from personal experience. After first reviewing the “rapid onset of ideas” effect, he then described the “time-slow” effect:

“But there are other phenomena that are still more characteristic of hasheesh, especially its effects on our notions of time and space. Under its influence, time seems to be of interminable length. Between two clearly-conceived ideas the patient descries a host of others that are indeterminate and incomplete, and of which he is only dimly conscious; but he is filled with admiration at their number and vastness. Now we measure time by the memory of the ideas that have passed through the mind, and hence an instant appears immensely long to one under the hasheesh influence. Suppose, as it is common enough in the use of this drug, that in the space for one second fifty different thoughts enter the brain; now, since in the normal state it requires several minutes to conceive fifty different thoughts, the inference will be that many minutes have gone by. Seconds become years, and minutes become ages.” (58)

The fact that the time-slow effects are one of the least discussed and least appreciated effects of cannabis use should be noted, and the fact that this same time-slow effect will both impair the novice user but enhance the performance of the chronic user should be stressed. Allen Ginsberg writes about time-slow in detail 86 years later, as is discussed in Chapter 9.

In the 1881 book titled Drugs That Enslave: the opium, morphine, chloral and hashisch habits, Dr. H.H. Kane makes the classic mistake – which continues to be made to this day – of confusing misuse (improper dosing) with all use. Beginning on page 213 Dr. Kane relates the story of a doctor who took “a very large dose” and then had a bad experience. From this Kane concludes;

“Wasting of the muscles, sallowness of the skin, hebetude (lethargy or stupidity) of the mind, interference with coordination, failure of the appetite, convulsive seizures, loss of strength, and idiotic offspring, seem, from all accounts, to be the uniform result of the long continued use of this drug.” (59)

Image #19: Drugs That Enslave : The Opium, Morphine, Chloral And Hashisch Habits, H. H. Kane, M.D., New York City, Presley Blakiston, Philadelphia, 1881

Image #19: Drugs That Enslave : The Opium, Morphine, Chloral And Hashisch Habits, H. H. Kane, M.D., New York City, Presley Blakiston, Philadelphia, 1881

None of the accounts of short-term use Kane related had anything whatsoever to do with that damning condemnation, however.

A similar tract came from an 1885 pamphlet titled A WEED THAT BEWITCHES, from the National Temperance Society. The pamphlet is mostly about tobacco, but has sections on opium and “hasheesh.” We are told that

“Whole nations have been stimulated, narcotized, and made imbecile with this accursed hasheesh. The visions kindled by that drug are said to be gorgeous and magnificent beyond all description, but it finally takes down body, mind, and soul in horrible death.” (60)

Image #20: Dw Witt Talmage, A Weed That Bewitches, New York, National Temperance Society, 1885

Image #20: Dw Witt Talmage, A Weed That Bewitches, New York, National Temperance Society, 1885

In 1885, a poet named Thomas Bailey Aldrich published a book of poems, one of which was called HASCHEESH. It seems likely a poem inspired by a hashish overdose. The last bars go like this:

“A terror seized upon me . . . a vague sense

Of near calamity. ‘O, lead me hence!’

I shrieked, and lo! from out a darkling hole

That opened at my feet, crawled after me,

Up the broad staircase, creatures of huge size,

Fanged, warty monsters, with their lips and eyes

Hung with slim leeches sucking hungrily.

Away, vile drug! I will avoid thy spell,

Honey of Paradise, black dew of Hell!” (61)

Also in 1885, the term “Ganja” appears – the Hindi term for “sinsemilla” or “seedless cannabis flowers” (62) – in newspapers, and not for the first time. But this time, the demonization, prejudice, bigotry and white supremacism is applied to the cannabis user in a big way – the “frenzy” of the “ganja eater” is examined in detail:

“A ganja eater is a criminal of which we have no counterpart in this country. He is an Asiatic monster. We hear, no doubt, of men being ‘mad with drink;’ but their frenzy differs both in degree and kind from that which results from indulgence in the juice of the hemp. For ganja is a preparation of this herb, and, though its prediction is punishable by the laws in India, is unfortunately so easy to procure that crime from this cause is constantly occurring. Thus in the latest Indian papers we find a case of a man, brutalized by its use, stabbing right and left in a Bombay bazar, and note that the magistrate, when passing sentence, deplored the increase in this ‘most dangerous class,’ the ‘ganja eating people.’ . . . The opium eater is an innocuous and harmless person. He injures no one but himself; he sins, perhaps, by omission, but not by commission. The ganja eater, on the other hand, is invariably a law breaker. He becomes at once a criminal. The villainous decoction seems to have the strange power of bringing to the surface all that is vicious and bad in its most violent form. Of such men murderers and assassins are made. In the Ghazi villages it is ‘ganja’ or ‘bang,’ as the different preparations of hemp are called, which is used for the stimulation of the fanatics, who are then sent out into the world to ‘run a-muck’ and to kill and be killed ‘for the faith.’” (63)

The article then goes on to link the word “assassin” with hashish (this time in the form of an “awful paste” which turns people into frenzied murderers). The anti-ganja section of the article was reprinted a couple months later as a stand-alone article called “INDIA’S NARCOTICS.” (64)

Interestingly, the first mention of “marijuana” – Mexican slang for cannabis flowers – in the newspapers that this author could locate contained no discernable stigma. In an 1886 story about the Mexican Army, this description of marijuana came close to being an endorsement:

“The soldiers have a herb named marijuana, which they roll into small cigaros and smoke. It produces intoxication which lasts for five days, and for that period they are in paradise. It has no ill after-effects, yet the use is forbidden by law.” (65)

The duration – five days – is an exaggeration, but “paradise” and “no ill after-effects” is accurate enough. For the vast majority of users throughout history cannabis has been used as an effective relaxant (66) and anti-depressant/euphoric (67) – as close as most humans get to paradise. And used properly, the after-effects are indeed negligible. (68)

This lack of stigma indicates to this author that “marijuana” wasn’t a racist word meant to disparage, it was a Mexican word that Mexicans themselves used in an affectionate manner and then subsequently used by racist white supremacist journalists to provoke fear and hysteria around the use of marijuana by associating it with Mexicans – who were also largely feared and misunderstood by the same white journalists.

The very next year, the stigmatization of the word “marihuana” began;

“Jesus Molinez, of Zacatecas, whose girl had been untrue to him, committed suicide by smoking several enormous cigarettes of marihuana, while lying in a pool abounding with venomous insects, which, while he was insensible, destroyed his life.” (69)

It’s possible that this reporter got the story backward. While it is true that cannabis can be used as a pain-killer, it’s also true that it can be used to stretch the sensation of time. Instead of causing Molinez to be “insensible,” the marihuana might have enhanced his senses. Each sting would be amplified, and with the time-slow effects of cannabis, the last moments of agony would seem like hours. If the story was true, using marihuana was probably a terrible choice of drug to assist in suicide – unless seemingly endless agony was the desired effect.

The same year, white users of hashish were treated much differently in the press. In an article about a club that was no doubt inspired by the Club des Hashischins, one journalist noted that such an organization reformed in Paris in some form or another thirty years later:

“Hasheesh is superseding morphine and vaporized ether, it is said, in the affection of the Parisian dilettanti drunkards. They have founded a Hasheesh club on the Rue St. Michel, where they meet every Friday. The amount of the drug which each shall take is prescribed by a doctor, and the dose is prepared by a chemist, both members of the club. It is taken in pills, and not chewed, drunken, or smoked, as are the oriental fashions. Each of the members is bound to describe to the others, either in writing or verbally, his sensations as the drug gains its influence over him.” (70)

Under the headline “POWER OF HASHEESH”, an 1890 article in the Pittsburg Dispatch misinformed its readers as to the level of severity of addiction and toxicity that hashish provided:

“Hasheesh-coufect is made and sold by nearly all American confectioners. But a demon lurks within the sugar. Once tasted, it is no easy matter to vanquish the subsequent desire for it. Upon the most it has the same effect that the first taste of human blood has upon a tiger. But in course of time the quantity has to be increased in order to produce the desired effect, and the eventual consequence is death. A French physician practicing in Cairo put it very truly into the following laconic phrase: ‘Opium kills slowly, hasheesh speedily and beautifully.’” (71)

In the Christmas 1892 edition of the Illustrated London News, a short story by Grant Allen and illustrated by Amedee Forestier was published. Titled “Pallinghurst Barrow,” it provided an example of the hallucinations that came with a “medicinal dose” of hashish tincture. (72) These hallucinations included visiting with skeletons and cave-people.

Image #21: Grant Allen, “Pallinghurst Barrow,” Illustrated London News, 1892, illustrated by Amedee Forestier

Image #21: Grant Allen, “Pallinghurst Barrow,” Illustrated London News, 1892, illustrated by Amedee Forestier

Image #22: Grant Allen, “Pallinghurst Barrow,” Illustrated London News, 1892, illustrated by Amedee Forestier

Image #22: Grant Allen, “Pallinghurst Barrow,” Illustrated London News, 1892, illustrated by Amedee Forestier

In 1893, the first genuine attempt at establishing a “reefer madness” theory in the public mind by a government took place. But they didn’t call it “reefer madness” – they called it “ganja mania.” The word “ganja”, of course, is Hindi for “sinsemilla” or “seedless buds” – in other words, high quality marijuana. (73) In that year, the British Government appointed the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission – empowered to investigate, amongst other things, a reported “high incidence” of ganja-related mania in Indian lunatic asylums. (74) What they found, however, was that it was an ordinary practice “to enter hemp drugs as the cause of insanity where it has been shown that the patient used these drugs” and that, in many cases, the “cause of insanity” was automatically changed from “unknown” to “ganja smoking.” (75)

Image #23: Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Volume 1, Hardinge Simpole, National Library of Scotland, 1894 (2010 edition)

Image #23: Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Volume 1, Hardinge Simpole, National Library of Scotland, 1894 (2010 edition)

Image #24: Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Volume 1, Hardinge Simpole, National Library of Scotland, 1894 (2010 edition)

Image #24: Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Volume 1, Hardinge Simpole, National Library of Scotland, 1894 (2010 edition)

Image #25: Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Volume 1, Hardinge Simpole, National Library of Scotland, 1894 (2010 edition)

Image #25: Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Volume 1, Hardinge Simpole, National Library of Scotland, 1894 (2010 edition)

Image #26: Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Volume 1, Hardinge Simpole, National Library of Scotland, 1894 (2010 edition)

Image #26: Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Volume 1, Hardinge Simpole, National Library of Scotland, 1894 (2010 edition)

A 2001 analysis of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission (IHDC) published by the American Bar Association went into great detail as to how the myth of ganja mania became entrenched in the minds of the colonial establishment in India, devoting many pages to the subject. Here is a small sample:

“The commission exposed the fact that British India’s civil surgeons and asylum superintendents were only remotely involved in establishing causes of insanity. Patients typically arrived at asylums equipped with a descriptive roll (form C) containing biographical details that included the ‘cause of insanity.’ This descriptive roll was routinely filled in by the local magistrate who ordered the person to an asylum, the magistrate himself often relying on information provided by the police. Both magistrates and police officers considered hemp as the cause of insanity if they found out from the insane or his relatives that the person consumed the drug. . . . The IHDC therefore concluded that the asylum statistics of India were fragrantly untrustworthy. Dismayed at its discovery, the IHDC accused the medical officers of India for bolstering a myth, suggesting that ‘this popular idea (about ganja and insanity) has been greatly strengthened by the attitude taken up by Asylum Superintendents’ who ‘assisted by the statistics they have supplied and by the opinions they have expressed in stereotyping the popular opinion and giving it authority and permanence’ (IHDC [1894] 1971, 1:226).” (76)

This type of deliberate “stigmatization through insanity causation assumption” occurred throughout the next 130 years of journalism regarding cannabis use – and still happens to this day – but from 1895 onward it would be propelled into the forefront of the public mind through illustrations and photographs and images. These visuals were the extra attention needed to take this scapegoating campaign to the next level, for it was images – not text – that gave the stigmatization the power needed to cement the reality of cannabis psychosis in the collective consciousness and push public opinion to the point where genocidal public policy could be created.

Citations:

- https://biblehub.com/library/richardson/early_christian_fathers/to_the_ephesians.htm

- http://www.katapi.org.uk/ApostolicFathers/Ignatius-Ephesus.html

- Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Volume 1, Hardinge Simpole, National Library of Scotland, 1894 (2010 edition), p. 225

- “…marijuana prohibition is psychedelic genocide against chicanos, blacks and whites who use it …” “Psychedelic Genocide”, Michael Aldrich, International Times #99, March 11th-25th 1971; See also: https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2010/01/13/gentle-genocide/ https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2018/12/20/be-the-change-how-to-defend-yourself-in-court-from-legalization/

- Mark Merlin, Man and Marijuana, Barns and Co., 1973, quoted in Cannabis and the Soma Solution, Chris Bennett, 2010, TrineDay, Walterville, Oregon, pp. 452-453

See also: “The Soma-Haoma Question,” Chris Bennett, January 27, 2020 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2020/01/27/the-soma-haoma-question/ - Exodus 30:23: “Take the finest spices: of liquid myrrh five hundred shekels, and of sweet-smelling cinnamon half as much, that is, two hundred and fifty, and of aromatic cane two hundred and fifty.” (Exodus 30:23, RSV), The Facts about Kaneh Bosem By Jeff A. Benner https://www.ancient-hebrew.org/studies-words/facts-about-kaneh-bosem.htm See also: Sula Benet, EARLY DIFFUSION AND FOLK USES OF HEMP, from “Cannabis and Culture,” Rubin, Vera & Comitas, Lambros, (eds.) 1975. 39-49 https://www.קנאביס.com/wp-content/PDF/EARLY-DIFFUSION-AND-FOLK-USES-OF-HEMP-SULA-BENET.pdf

Exodus 30:30-33: “30 ‘Anoint Aaron and his sons and consecrate them so they may serve me as priests. 31 Say to the Israelites, ‘This is to be my sacred anointing oil for the generations to come. 32 Do not pour it on anyone else’s body and do not make any other oil using the same formula. It is sacred, and you are to consider it sacred. 33 Whoever makes perfume like it and puts it on anyone other than a priest must be cut off from their people.’” https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus%2030-31&version=NIV

See also: Sex, Drugs, Violence and the Bible, Chris Bennett & Neil McQueen, 2001, Forbidden Fruit Publishing, Gibsons, BC, pp. 71-72 - William Emboden, “Ritual Use of Cannabis Sativa L” in Flesh of the Gods, 1972, as quoted in Green Gold, Chris Bennett, 1995, Access Unlimited, p. 96

See also Potshot #17, pp. 90-95 at https://pot-shot.ca/ - The New Westminster Dictionary of the Bible, The Westminster Press, 2 Kings 22:1-2; 2 Chron. 34: 1-7, 33, 2 Kings 22:17, The New American Bible – new Catholic translation – Nelson, 1970, as quoted in Green Gold, Chris Bennett, Lynn Osburn & Judy Osburn, 1995, Access Unlimited, pp. 354-359

- “The text of the Ten Commandments appears twice in the Hebrew Bible: at Exodus 20:2–17 and Deuteronomy 5:6–21. . . . Dating: Archaeologists Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman argue that ‘the astonishing composition came together… in the seventh century BC’. An even later date (after 586 BC) is suggested by David H. Aaron.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ten_Commandments “Traditionally ascribed to Moses himself, modern scholars see its initial composition as a product of the Babylonian exile (6th century BCE), based on earlier written sources and oral traditions, with final revisions in the Persian post-exilic period (5th century BCE).” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Exodus “Josiah ordered the High Priest Hilkiah to use the tax money which had been collected over the years to renovate the temple. While Hilkiah was clearing the treasure room of the Temple he discovered a scroll described in 2 Kings as ‘the book of the Law’, and in 2 Chronicles as ‘the book of the Law of the LORD given by Moses’. The phrase sefer ha-torah (ספר התורה) in 2 Kings 22:8 is identical to the phrase used in Joshua 1:8 and 8:34 to describe the sacred writings that Joshua had received from Moses. The book is not identified in the text as the Torah and many scholars believe this was either a copy of the Book of Deuteronomy or a text that became a part of Deuteronomy.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Josiah

- Sex, Drugs, Violence and the Bible, Vol. 2, pp. 47-48

See also: Did Jesus Heal With Cannabis? Chris Bennett 2016, Cannabis culture https://www.academia.edu/44695043/Did_Jesus_Heal_With_Cannabis - “They drove out many demons and anointed many sick people with oil and healed them.”

Mark 6:13, New Testament, New International Version https://biblehub.com/mark/6-13.htm - Sex, Drugs, Violence and the Bible, Vol. 2, pp. 60-66

- Matthew 15:11, New Testament, New Living Translation, https://biblehub.com/matthew/15-11.htm

- Ignatius, third Bishop of Antioch, “To the Ephesians,” circa 107–110 CE, Cyril C. Richardson 1953 translation, https://biblehub.com/library/richardson/early_christian_fathers/to_the_ephesians.htm

- “Affidavits from My case against the Federal government and the Crown’s case against the G13,” Chris Bennett, March 19, 2010 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2010/03/19/religious-cannabis-case-updates-affidavits-my-case-against-federal-government-and-c/

- Sex, Drugs, Violence & the Bible, Vol. 2, p. 206

- Ibid, Vol. 2, pp. 213-214

- Ibid, Vol. 2, p. 215

- https://www.historyofengland.net/kings-and-queens/the-dark-ages-complete

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_paper

- Liber 420: Cannabis, Magickal Herbs and the Occult, Chris Bennett, 2018, TrineDay, Walterville, Oregon, p. 73

- Manchester Weekly Times and Examiner, Nov. 16, 1847, p.3

- Liber 420, pp. 59-86

- Ibid, pp. 183-184

- Ibid, pp. 384, 437

- Ibid, p. 437

- Ibid, pp. 451-479

- Ibid, p. 501

- Ibid, p. 502

- Rabelais seemed to hint, at one point, to cannabis helping humans either unlock the mysteries of flight or more probably the inner workings of the cosmic forces: “Who knows but by his sons may be found out an herb of such another virtue and prodigious energy, as that by the aid thereof, in using it aright according to their father’s skill, they may contrive a way for humankind to pierce into the high aerian clouds …” CHAPTER 51, (Chapter 3.LI.—Why it is called Pantagruelion, and of the admirable virtues thereof) GARGANTUA AND HIS SON PANTAGRUEL, Francois Rabelais, 1653 https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1200/1200-h/1200-h.htm Rabelais may have also attempted to reveal it’s psychoactive effects without appearing to be doing so – giving himself a way to argue out of accusations of witchcraft should they arise. In Chapter 52, (Chapter 3.LII.) subtitled “How a certain kind of Pantagruelion is of that nature that the fire is not able to consume it.” Rabelais talks alcohol and then about trying to set hemp on fire to see if it’s the special kind of hemp that won’t burn. Finally, the revelation that the herb “Pantagruelion” is actually hemp was left out of some translations (John M. Cohen translation, 1982, Franklin Library, pp. 411-423), but was published posthumously in other translations (Sir Thomas Urquhart / Peter Antony Motteux translation, 1653, reprinted in 1894, Moray Press, Derby

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1200/1200-h/1200-h.htm, Jacques Le Clercq translation, 1936, Random House, p. 666) See also chapter 13 of Liber 420, pp. 281-346 - Shakespeare spoke of “compounds strange” to help him put variation in his verse, along with “invention” found in a “noted weed” in Sonnet 76. Liber 420, pp. 481-496. See also: “Weed” was already being used as a slang word for tobacco by Shakespeare’s time: “weed (n.) ‘plant not valued for use or beauty,’ Old English weod, uueod ‘grass, herb, weed,’ from Proto-Germanic *weud- (source also of Old Saxon wiod, East Frisian wiud), of unknown origin. Also applied to trees that grow abundantly. Meaning ‘tobacco’ is from c. 1600 . . .” https://www.etymonline.com/word/weed

Four pipes found in Shakespeare’s garden from Shakespeare’s time were analyzed and found to have cannabis and other drug residues. South African Journal of Science, Volume 111, Issue 7/8, pp. 5-6, July 30, 2015

https://time.com/3990305/william-shakespeare-cannabis-marijuana-high/ https://www.openculture.com/2015/08/pipes-with-cannabis-traces-found-in-shakespeares-garden.html - Hooke, R. (1726). “An account of the plant, call’d Bangue, before the Royal Society,” Dec. 18. 1689. In W. Derham (Ed.) Philosophical experiments and observations of the late eminent Dr. Robert Hooke, S. R. S. and geom. prof. Grelb and other eminent virtuoso’s in his time, London: W. Derham., p. 210

- Koerner, L. (1999). Linnaeus: Nature and nation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 41

- Joseph Miller, (1722), Botanicum officinale, or, A compendious herbal : giving an account of all such plants as are now used in the practice of physick, with their descriptions and virtues, London: Printed for E. Bell, J. Senex, W. Taylor, and J. Osborn, pp. 107-108

- https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Volume%3AWashington-01-01&s=1511311112&r=550

- “…his phrase ‘rather too late’ suggests that he wanted to complete the separation *before the female plants were fertilized* – and this was a practice related to drug potency rather that to fiber culture.” http://www.erowid.org/plants/cannabis/cannabis_history2.shtml

- https://founders.archives.gov/?q=%22India%20hemp%22&s=1511311112&sa=&r=1&sr=

- https://founders.archives.gov/?q=%22India%20hemp%22&s=1511311112&sa=&r=3&sr=

- Colonel Kirkpatrick’s “An Account of the Kingdom of Nepaul; being the Substance of Observations made during a Mission to that Country, in the Year 1793”, Quarterly Review, May 1811, p. 323

- “ANECDOTES OF THE ORIGIN OF WORDS”, Belfast News-Letter, Sept. 15, 1837, p. 4

- “Anecdotes of the Origin of Words.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Nov. 23, 1844, p. 2

- O’Shaughnessy, W.B. (1843). “On the preparations of the Indian hemp, or Gunjah, (Cannabis Indica)”. Prov Med J Retrosp Med Sci. 5 (123): p. 1

- Ibid, p. 2

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Club_des_Hashischins

- Ibid.

- CHARLES BAUDELAIRE: HIS LIFE BY THÉOPHILE GAUTIER, TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH, WITH SELECTIONS FROM HIS POEMS, “LITTLE POEMS IN PROSE,” AND LETTERS TO SAINTE-BEUVE AND FLAUBERT AND AN ESSAY ON HIS INFLUENCE BY GUY THORNE, LONDON, GREENING & CO, 31 ESSEX STREET, STRAND, W.C., 1915

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47075/47075-h/47075-h.htm - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Les_Paradis_artificiels

- CHARLES BAUDELAIRE: HIS LIFE BY THÉOPHILE GAUTIER, 1915

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47075/47075-h/47075-h.htm - Moreau, J. J. (1973), Hashish and mental illness, H. Peter & G. G. Nahas, Eds., G. J. Barnett, Trans., New York: Raven Press. (Original work published 1845), p.68 2)

- Ibid, p. 211

- “Starting with a small amount and gradually increasing the dose is the key to avoiding unwanted mental side effects. This is called titration – self-titration if adjusted by the user.” “Safe Use of Cannabis,” Tod H. Mikuriya, M.D., 11/24/93 http://druglibrary.org/schaffer/hemp/safeuse.htm “An experienced cannabis smoker can titrate and regulate dose to obtain the desired acute effects and to minimize undesired effects.” “Medicinal cannabis: Rational guidelines for dosing,” Gregory T Carter, Patrick Weydt, Muraco Kyashna-Tocha & Donald I Abrams, IDrugs, 2004 7(5):464-470 https://www.coscc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Abrams-Medicinal-Cannabis-Rational-Guidelines-for-Dosing-.pdf

- Alexandre Dumas, The Countess De Charny, taken from The Works of Alexandre Dumas, Volume 9, Peter Fenelon Collier, New York, 1893, p. 145

- Mills, James H., Madness, Cannabis and Colonialism, St. Martin’s Press, London, 2000, p. 57

- Ibid.

- “INCOMPETENTS AND THEIR ESTATES,” The Baltimore Sun, March 26, 1872, p. 2

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Richet

- Charles Richet, “POISONS OF THE INTELLIGENCE – HASHEESH,” The Popular Science Monthly, August, 1878 p. 483

- Ibid, p. 484

- Dr. H. H. Kane, Drugs That Enslave: the opium, morphine, chloral and hashisch habits, 1881, P. Blakiston, Son & Co., Philadelphia, p. 218. See also: “Dr. H. H. Kane and the 19th Century ‘Hash-Heesh’ Smoking Parlors of NYC,” David Malmo-Levine, April 2, 2021 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2021/04/02/dr-h-h-kane-and-the-19th-century-hash-heesh-smoking-parlors-of-nyc/

- T. Dw Witt Talmage, A Weed That Bewitches, New York, National Temperance Society, 1885, p. 9

- THE POEMS OF THOMAS BAILEY ALDRICH, Household Edition, WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BOSTON AND NEW YORK, HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY, The Riverside Press, Cambridge, 1885 https://quod.lib.umich.edu/a/amverse/BAD9188.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext

- “History of Cannabis as a Medicine,” Ethan Russo, The Medicinal Uses of Cannabis and Cannabinoids, 2004, Geoffrey W. Guy, Brian A Whittle, Philip J. Robson, editors, Pharmaceutical Press, London, p.9

- “The Ganja Eater,” The Daily Republican, Aug. 24, 1885, p.3

- “INDIA’S NARCOTICS”, Lawrence Daily Journal, Oct. 1st, 1885, p.3

- “The Mexican Army”, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Sept. 10th, 1886, p.6

- “A Brief History of the Use of Cannabis as an Anxiolytic, Hypnotic, Nervine, Relaxant, Sedative, and Soporific,” David Malmo-Levine and Rob Callaway, M.A., 2012

https://www.academia.edu/11761753/A-Brief-History-of-the-Use-of-Cannabis-as-an-Anxiolytic-Hypnotic-Nervine-Relaxant-Sedative-and-Soporific - “A Brief History of the Use of Cannabis as an Antidepressant and Stimulant,” David Malmo-Levine and Rob Callaway, M.A., 2012 https://www.academia.edu/11761666/A-Brief-History-of-the-Use-of-Cannabis-as-an-Antidepressant-and-Stimulant

- “Does Cannabis Inherently Harm Young People’s Developing Minds?” David Malmo-Levine, Cannabis Culture on November 11, 2014 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2014/11/11/does-cannabis-inherently-harm-young-peoples-developing-minds/

- “Senseless Brutality,” Memphis Appeal, April 25th, 1887, p. 1

- “A Hasheesh Club,” The Evening Kansan, Dec. 5th, 1887, p. 3

- “POWER OF HASHEESH,” Pittsburg Dispatch, Jan. 19th, 1890, p. 17

- Grant Allen, “Pallinghurst Barrow,” Illustrated London News, 1892, illustrated by Amedee Forestier, pp. 12-18 http://gaslight-lit.s3-website.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/gaslight/palling.htm

- “History of cannabis as a medicine”, Ethan Russo, The Medicinal Uses of Cannabis and Cannabinoids, 2004, Edited by Geoffrey Guy, Brian Whittle and Philip Robson, Pharmaceutical Press, London, p. 9

- “The Commission took testimony from 1,193 witnesses and examined the records of every mental hospital, since the presumed high incidence of so called ‘ganja mania’ in Indian lunatic asylums was one of the factors that prompted the appointment of the Commission.” Vera Rubin, Lambros Comitas, Ganja In Jamaica, 1976, Anchor Books, Garden City, NY, p. 17

- Ibid, p. 19, see also Report of the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission 1893-94, Volume 1, Hardinge Simpole, National Library of Scotland, 1894 (2010 edition), p. 232: “Finally, the distrust of the descriptive roll must be further intensified by the consideration of the pressure brought to bare on subordinates to supply information as to cause. An illustration of this may be found as early as 1863 in the Resolution of the Government of Bengal on the Asylum Reports for 1862. And a striking illustration of the effect of this pressure is found in the Dullunda Asylum returns for the following year (1863), in which the cause in several cases dating from the year 1857 and onwards was altered from ‘unknown’ to ‘ganja smoking’.” P. 236: “Surgeon-Lieutenant-Colonel Leapingwell (Vizagapatam) says: ‘I should myself have put down ganja as the cause of insanity in any case where I examined the friends if they merely said the man used ganja and I could get no other cause, as I did not discriminate between the excessive and moderate use.’ … Surgeon-Major Willcocks, of Agra, says: ‘Ordinarily it has been the practice to enter hemp drugs as the cause of insanity where it has been shown that the patient used these drugs. I cannot say precisely why this is the practice. It has come down as the traditional practice.”

- Ronen Shamir and Daphna Hacker, ”Colonialism’s Civilizing Mission: The Case of the Indian Hemp Drug Commission,” American Bar Foundation, 2001, pp. 445, 447

https://en-law.tau.ac.il/sites/law-english.tau.ac.il/files/media_server/Law/faculty%20members/Daphna%20Hacker/CV%20LINKS/papers/1%20Colonialism%20s%20Civilizing%20Mission.pdf