New Series: Reefer Madness – 1895 to the Present – Introduction

“Medicine in the hands of the foolhardy is poison, as poison becomes medicine in the hands of the wise.”

– Giacomo Casanova, History of My Life, circa 1789 (1)

“The process of going outside, going beyond learned modes of experience (particularly the learned modes of space-time-verbalization-identity), is called ecstasis. The ecstatic experience. Ex-stasis. . . . Those who are concerned with conformity and adjustment like to call the ecstatic state psychotic.”

– Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, and Ralph Metzner, “Rationale of the Mexican Psychedelic Training Center,” from Utopiates, 1965 (2)

“One of the problems that the marijuana-reform movement consistently faces is that everyone wants to talk about what marijuana does, but no one ever wants to look at what marijuana prohibition does. Marijuana never kicks down your door in the middle of the night. Marijuana never locks up sick and dying people, does not suppress medical research, does not peek in bedroom windows. Even if one takes every reefer madness allegation of the prohibitionists at face value, marijuana prohibition has done far more harm to far more people than marijuana ever could.”

– William F. Buckley Jr., quoted by Allen St. Pierre, “The Heritage Foundation: A Last Refuge For Reefer Madness?” norml.org, OCTOBER 17, 2010 (3)

Image #1: The Beatles – “having a laugh” – taken from A DAY IN THE LIFE OF THE BEATLES, Don McCullin, Jonathan Cape/Random House, London, 2010, p. 106

Author’s note: This series was created with the support of the Cannabis Museum. Please check out their website at https://www.cannabismuseum.com/

Chapter 1 – “Human and Cannabis Coevolution” – can be found here.

Reefer Madness! The term originally meant a form of insanity caused by smoking reefers, but has come to mean many other things, such as the insanity of anti-pot propaganda, or the insanity of anti-pot legislation, or the insanity of “protecting” the vulnerable through their criminalization, or the insanity experienced by victims of anti-pot laws arising out of a denial of medical autonomy or a denial of a vocation needed to survive or of repeated exposures of brutality and sometimes murder from the anti-pot police, or the insanity of corporate greed now attempting to carve out an exclusive position growing or selling weed while other, less fortunate individuals remain in jail for growing or selling weed.

For this author, Reefer Madness has come to mean the ridiculous lengths that the establishment goes to in the attempt to foist stigma onto the pot community – a community who by now are in possession of overwhelming evidence that they are a harmless, helpful nation – a community who are undeserving of that stigma.

Perhaps one day, with the help of resources such as this new series of articles you have begun reading now, Reefer Madness will also come to mean the stigmatization of humanity’s co-evolutionary plant partner in order to subjugate and enslave the underclass at the expense of a fascistic genocide of the medically autonomous and environmental destruction from climate-destabilizing, toxic substitutes to industrial hemp in general, and hemp ethanol in particular.

The concept of “ganja mania” or a “weed craze” or “reefer madness” or “cannabis psychosis” as a pot-use-related mental illness has persisted from the late 19th century to modern times. It is not, as some believe, a result of a careful collective diagnosis of an existing mental condition manifesting from an objective weighing of the medical evidence. It is, rather, a manifestation of a paradox of cultural evolution.

That paradox is this: instead of benefitting from a more modern, sophisticated medical system, modern humans are suffering from a more modern, sophisticated scapegoating system. Our collective achievements in medicine, in ethics, in peaceful coexistence and economic harmony have not kept pace with our advancements in systems of avarice, medical doublespeak and intellectual fraud. Greed, competition and short-term self-interest has stunted our evolution and is threatening our survival.

Image #2: Peter Tosh. Taken from ONE LOVE: Life with BOB MARLEY and The Wailers – Words and Photographs by Lee Jaffe, W.W. Norton & Company, New York – London, 2003, p. 149

If we evaluate the creation of the myth of Reefer Madness as a strategy to keep cannabis illegal forever, it can be seen as a resounding failure. More and more US States and more and more countries around the world are legalizing pot. But if we instead see the creation of the myth of Reefer Madness as a strategy to control and subjugate people by stigmatizing their most important resource (cannabis) and stigmatizing (some of) those who use, grow and sell cannabis, then it continues to be a resounding success – even post-legalization. Pot prohibition controls people in one way, and the pot cartel (which “cannabis psychosis” is used to justify) controls them in another way.

But we are not totally doomed. There is still some hope.

Cannabis – if regulated reasonably and used to its maximum potential – can help save the world. The plant – after its full legalization (legal for all users, growers and dealers) – can do this in a number of ways.

The first way involves the fact that cannabis is the most useful and versatile medicine (when used properly) and the co-evolutionary plant partner of humanity – our most useful resource and our best source of economic independence for individuals who wish to participate in the re-emerging herbal medicine economy.

With the ability to be manufactured into pressed particle board, concrete, plastics, fabrics, paper, food, medicine, fuel and tens of thousands of other raw materials and products, cannabis/hemp can help replace virtually any material other than glass or metal. Let me repeat that astounding point to drive it home: cannabis/hemp can help replace virtually any material other than glass or metal.

Grown as a fuel crop, hemp is probably the best producer of cellulose on earth. Cellulose is a carbohydrate, which – according to today’s chemists – has the potential to replace the hydrocarbon (fossil fuel) sector of the economy:

“The rest of our energy generation, storage, and distribution needs could be met using existing and emerging technologies, including photovoltaic and wind generation, fuel cells, hydrogen generation, and carbohydrate chemistry. In principle, anything that can be made from hydrocarbons can be made from carbohydrates.” (4)

As a herbal medicine with the ability to replace more toxic, dangerous and expensive synthetic medicines, no other herb even comes close. Cannabis has over 100 cannabinoids and over 200 terpenes, all of which are under-researched due to their non-proprietary nature. But the ones that have been studied carefully show a lot of promise as medicines. (5)

Image #3: The author, enjoying a solar bowl, circa October 1996, East Vancouver, photographer unknown.

This herb can ease many a disease, help keep us all healthy and – if we are all given access to the pot economy – help keep us all moderately wealthy too. It can help each and every one of us in one way or another, if we learn how to share it – and share the pot economy – rather than to continue to either prohibit marijuana and over-regulate industrial hemp it for the sake of promoting the sale of inferior-but-easier-to-monopolize substitutes, or to tightly regulate marijuana in an attempt to create a cartel for suppliers.

Cannabis prohibitions and cartels are methods of enslaving humanity – either through wage slavery in largely capital-intensive chemical-dependent synthetic cannabis-substitute industries, or becoming a wage slave for one of the lucky few pot-license holders, or through the outright slavery of prison labor waiting for those who run afoul of cannabis laws. Without free and easy access to our co-evolutionary plant partner, we are weakened and easily exploited. And it doesn’t matter if it’s a bureaucratic socialist nanny-state like Uruguay, or the late-stage capitalist nightmare of countries such as the USA and Canada – our rulers always organize society so that someone’s thumb is on your neck. “The population under control” is the feature common to almost all economic and political systems.

In 1810, approximately 84 percent of the U.S. labor force was involved in agriculture. (6) By 2020, that same statistic had shrunk down to about 10 percent. (7) Every time I see someone begging in the streets, or witness the misery and desperation of homeless people and their tent cities, I wonder what the effects of an inclusive, diffused, window-box pot economy would have on poverty rates and on the poor. Instead of a handful of privileged growers and dealers, there should be scores of ma and pa operations, each one working with a small army of bud trimmers, bud tenders, transporters, tour guides and those involved in a million other spin-off industries. This inclusive pot economy only exists in a few small out-of-the-way places, but there’s no reason why it could not exist everywhere.

Image #4: The author, enjoying a solar bowl, circa December 1996, East Vancouver (same window) photographer unknown.

The second way cannabis can save the world is through cannabis activists using cannabis law reform to establish legal precedent for herbal autonomy – and medical autonomy generally – in case law. Herbal and medical autonomy are paths towards total human liberty. Total pot legalization for all people may very well lead to an end to all scapegoating forever, by establishing a new legal precedent for when an activity can be criminalized (or even subject to non-criminal punishments) in the first place.

Nazi Germany was involved all kinds of scapegoating, including the Nazis launching their own drug war – they called it “Rauschgiftbekämpfung” – the “fight against drugs.” (8) Had they won World War 2, the global drug war would certainly have continued as it did – or perhaps it would have been much worse – while the persecution of left wingers, Jews, Romani, queers and all the other types of Nazi scapegoating would have persisted, likely becoming more sophisticated over time. Instead of Jews being “vermin,” they would have no doubt eventually been called “inherently pathological” or “deeply problematic.” Instead of propagandists and military men stigmatizing them, that job would probably have soon been passed on to doctors, theologists and other academics.

One need not study the history of scapegoating to notice how relevant this tactic is when it comes to today’s batch of totalitarians and their desire to gain power. Demonizing and stigmatizing vulnerable groups as a path to political power is still alive and well in the U.S. and Canada, as the rise of Trumpism and the creation of the People’s Party of Canada will attest to. Once again, immigrants, transexuals, drag-queens, Muslims, Jews, queers, drug users of all types and left wingers take their turns as scapegoat of the week, while our corporate masters who actually call the shots (often poorly) seem to always evade the corporate media’s critical eye. Humanity must become much better and differentiating between actually harmful behavior and stigmatized harmless behavior. Scapegoating must end forever, before it consolidates the career of the next Hitler and engulfs humanity in further misery, suffering and genocide.

Ending scapegoating would end the rest of the drug war, as society would stop the assault on the medically autonomous and everyone would then begin to see drugs as tools rather than temptations, and we would learn to use each drug properly and to one’s benefit. Ending the drug war would end the biggest war in the world (a civil war in every country on Earth) and the longest-running war in the world (if you count the burning of witches as an early phase of the drug war).

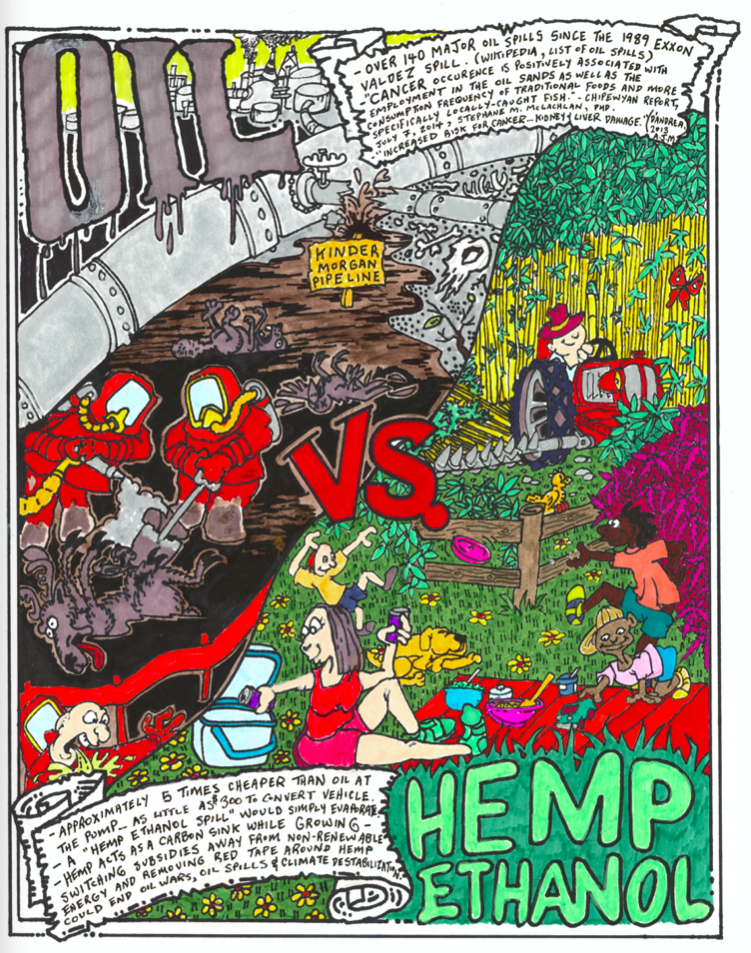

Image #5: “Hemp Biofuel: A Viable Alternative to Fossil Fuels?” Scarlet Palmer, Updated on 07/31/2020

But by far the most powerful and important way cannabis can save the world is through hemp ethanol. It is a little-known but undeniable fact that hemp ethanol made from cannabis stalks is the most economically viable carbon-negative renewable energy source on planet earth. All the other clean/renewable energy options are at best carbon-neutral. Only hemp ethanol has the potential to act as both a carbon sink and an economically viable, clean alternative to synthetic liquid fuels. Switching subsidies to renewable energy, factoring health and environmental costs into the cost of each product sold, and removing the red tape around industrial hemp growing might very well be the quickest and best way human beings can reverse the greenhouse effect and mitigate climate destabilization. The evidence for this is very compelling – but time is running out.

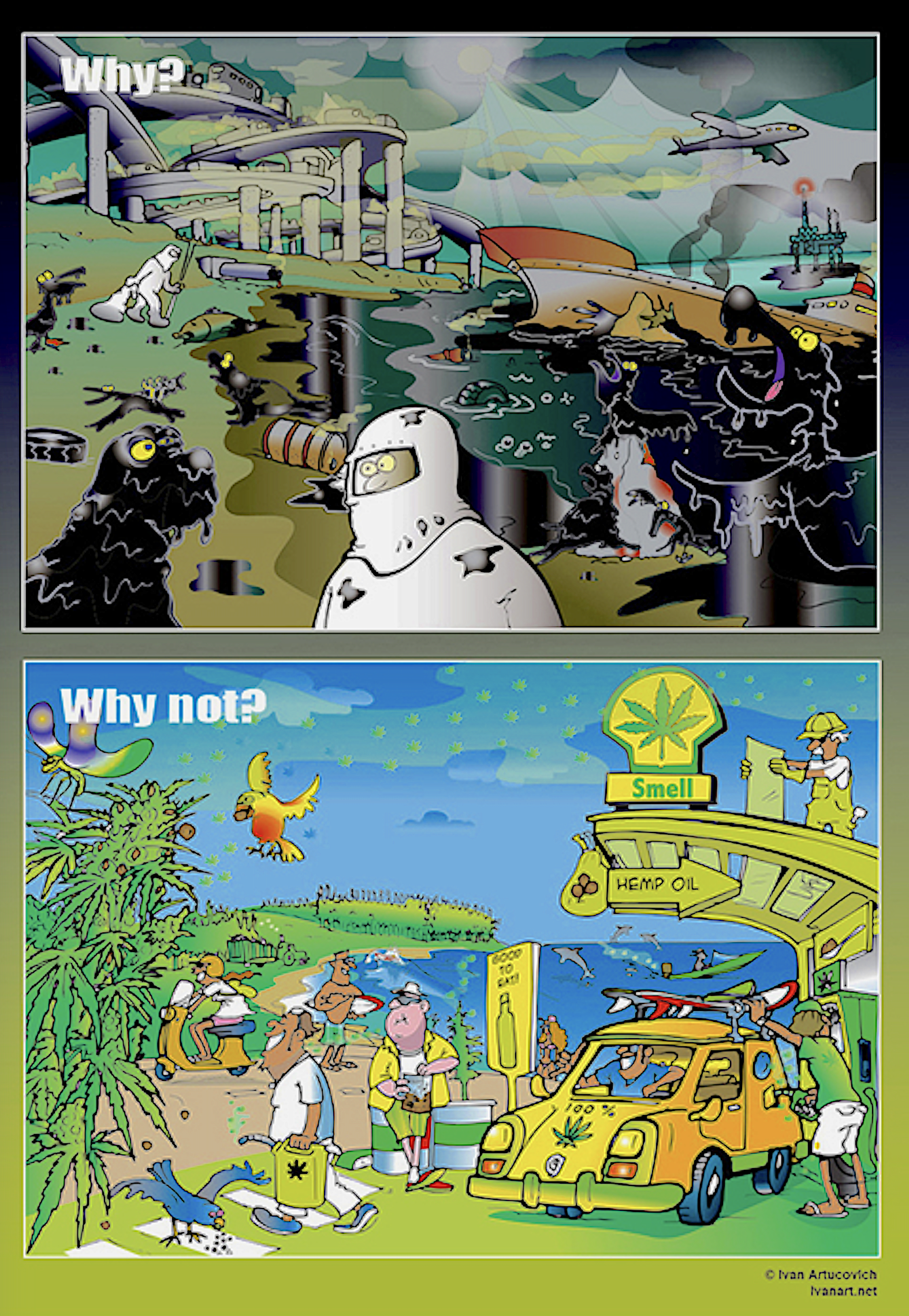

Image #6: “Poster why not? 006 Fossil fuels by WHY NOT? BY IVANART”

These benefits from cannabis will only come through reasonable pot regulations – the type of regulations that currently exist for some herbal medicines and for organic, fair trade coffee beans. Reasonable cannabis regulations will only arise through debunking the mythology of inherent cannabis harms. And the chief myth amongst the various myths of inherent cannabis harms is that smoking pot causes psychosis.

While it is true that acute cannabis poisoning (a non-lethal overdose) will cause a form of psychosis (confusion and discomfort – sometimes extreme discomfort) – this is a temporary situation. A caffeine overdose can do the same thing – or much worse. And there is some evidence that using cannabis might trigger a psychosis that already exists within the individual as a result of a genetic disposition, but this is not a causal relationship between cannabis and psychosis – it’s an opportunity to use cannabis as a diagnostic tool, in order to catch genetic-based psychosis early, and treat it early (possibly using CBD), leading to better health outcomes.

The reason this author can comfortably argue that all “cannabis use causes psychosis” arguments are fraudulent is that out of all the studies that this author has examined that make the argument that cannabis causes psychosis (and there have been at least 12 of them), only two have even attempted to address the best counter-evidence for that argument: that skyrocketing cannabis use rates in the general population between the early 1960s and the late 1990s (a five-fold increase according to some) have not been accompanied by any noticeable increase in psychosis rates. If cannabis use caused psychosis, then increased cannabis use rates would be followed by increased psychosis incidence. This hasn’t happened.

The two studies which have both argued that a) cannabis causes psychosis and b) have noted that increased cannabis use rates don’t correspond with increased psychosis rates have gone on to provide explanations for this fact which cannot in any way be said to be compelling.

Radhakrishnan et al. (2014) (9) – covered in Chapter 16 – called the increase in cannabis use rates with no “commensurate . . . increase in prevalence of schizophrenia . . . difficult to explain,” going on to say it was “possible” that there was a time lag between an actually observed and documented increase in cannabis use rates and some far off in the future potential increase in schizophrenia rates. A potential 40 to 50-year time lag that still hasn’t manifested. That’s quite the time lag.

Some might argue a potential, not-yet-manifested 50-year time lag could also be called “evidence to the contrary” – evidence of no causal relationship between cannabis use and psychosis – but Radhakrishnan (for some reason or another) didn’t.

The other study that argues cannabis causes psychosis and attempts to explain away the evidence that use rates and psychosis rates don’t track together is Di Forti et al. (2019) (10) – covered in Chapter 14. It appears that Di Forti tried to make the argument that higher use rates resulted in higher psychosis rates by cherry picking cities with high psychosis rates. They claimed (with no evidence at all to support this claim) that these cities had more “high-potency” pot than other cities not examined in their study, claimed also that countries such as France, Italy and Spain were places where high-potency cannabis products were “not yet available” (in spite of these countries serving as smuggling routes for high-potency hashish from North Africa into England and Holland for decades) and then purposely avoided looking at THC/CBD ratios in the available cannabis in question because (they say) there wasn’t enough data to make it worth their while.

This study did not directly address in any meaningful, detailed, comprehensive way any of the general population statistics involving cannabis use rates in many other studies (11) that indicate no association between use rates and psychosis rates. This study carefully avoided looking too closely at any national statistics, choosing to select cities instead of nations, which allowed cherry picking to occur.

This study did not make an effort to prove that the British hashish in the relatively sane British countryside was somehow less potent than the British hashish inside of psychotic London, nor did it mention the effects of cannabis prohibition or cannabis over-regulation on the THC/CBD ratios of black-market cannabis (prohibition makes CBD research, easy cannabinoid-testing-lab access, and THC/CBD breeding more difficult if not impossible) nor did it look closely at the evidence that CBD can treat psychosis. Chapter 16 examines a few of the many CBD studies that indicate CBD as an effective treatment for psychosis and other mental pathologies.

The rest of the studies that argue cannabis causes psychosis ignore the counter-evidence entirely. A careful examination of the above two studies – and the rest of the causal studies – are the best evidence that the “cannabis psychosis” idea is not based in science, rather, cannabis psychosis/Reefer Madness is a myth – a manifestation of a non-stop 130-year high-profile stigmatization campaign by the political and medical establishments that has persisted each and every decade, with vast resources employed to provide illustrations and photographs to accompany the campaign, with arguments becoming more sophisticated and sources becoming more accredited over time. The counter-evidence disproving this myth which has arisen in every decade since at least the 1970s has been largely ignored or dismissed – almost never addressed – by those making those causal arguments.

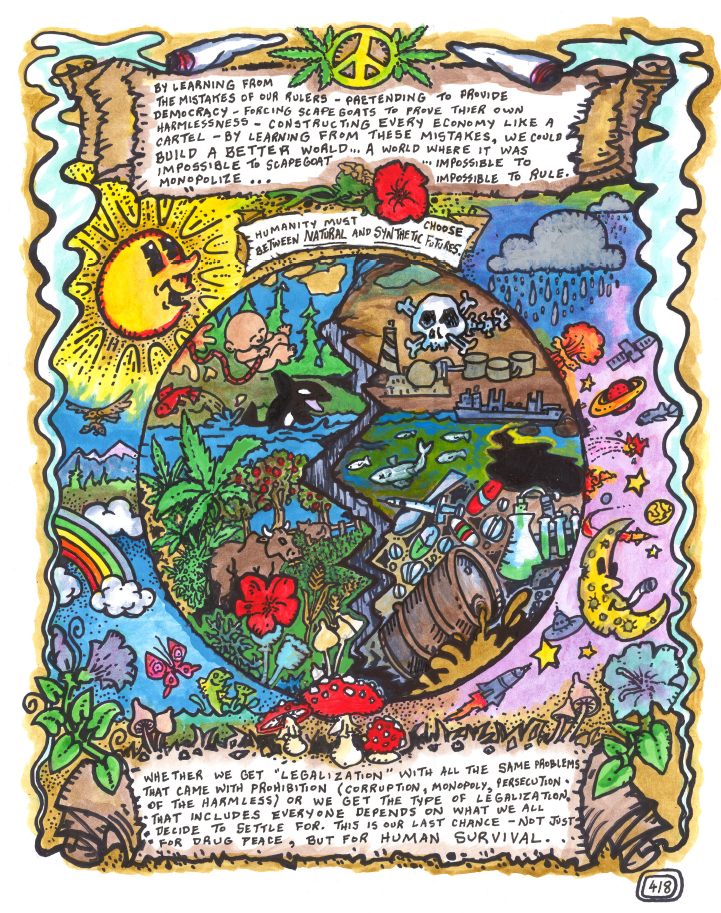

Image #7: Vansterdam Comix, David Malmo-Levine & Bob High, WEEDS, Vancouver, 2018, p. 418

This history of Reefer Madness is the best evidence of the fraud underlying most cannabis regulations. This fraud has been perpetrated by those who wish to help enslave humanity through helping to deny or limit access to our co-evolutionary plant partner – cannabis – and thus dooming human beings to either be artificially dependent on the suppliers of inferior cannabis substitutes, or artificially dependent on the recently-formed cannabis cartel which is now permitted to supply actual products from the actual plant. This series of articles traces that history, taking careful note of both the similarities of the anti-pot arguments and their increased sophistication decade by decade.

In Chapter 1 of this series we are introduced to cannabis our co-evolutionary plant partner, providing a peek at its true potential, unhindered by artificial, fraudulent, baseless stigmatization and demonization. A photo exhibit is provided, showing how different eras and ages depicted cannabis and cannabis users. In Chapter 2, we look at the ancient sources of – and pretexts for – demonization and stigmatization, before these myths were accompanied with illustrations and images within the mass media designed to amplify their effect upon public opinion.

In Chapter 3, we find images of delirious hemp eaters and violent, weed-crazed Mexicans emerging from newspapers between 1895 and 1909, painting a picture of cannabis as an insanity-inducing drug, even as the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission and the Ely Lilly pharmaceutical corporation reported evidence to the contrary. In Chapter 4, the machinations of powerful men come into play between 1910 and 1919, as the institutions of the establishment were used by these men to assist them with the beginning of the elimination of cannabis as an over-the-counter medicine – and folk medicine – from society.

In Chapter 5 – covering the 1920s – the scapegoating strategy of inducing parental hysteria became more common, increasing the likelihood of more severe punishments implemented against the scapegoat. Cannabis became illegal for sale or for possession in Canada during this period. In Chapter 6 – covering the 1930s – the new mediums of jazz music and Hollywood films added their perspective to a dialogue about marijuana already in progress in the mass media and in the public mind. A very high-profile axe murder – unfairly associated with marijuana smoking – was injected into this dialogue, which then culminated in the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, effectively prohibiting the sale and possession of cannabis in the United States.

In Chapter 7, the 1940s revealed cracks in the prohibitionist system, as the high-profile arrest of Robert Mitchum in 1948 resulted in the public rallying to support him in the movie theatres – the first signs of a backlash against the new national anti-pot laws. In Chapter 8, the Beatnik literary movement born in the 1950s joined with the jazz community to launch its own spirited resistance against the campaign to stigmatize cannabis.

In Chapter 9, leading figures of the 1960s hippie movement – especially Allen Ginsberg and John Lennon – lead an all-out revolt against the cannabis laws, which manifested in a major shift of public opinion and the beginning of the end of pot prohibition in North America. The 1960s began with stigmatization: pot was the gateway to heroin, rage and insanity. The decade ended with pot being too mysterious and misunderstood to make legal.

Chapter 10 deals with the 1970s, and begins with the two branches of the reform movement that would shape the way the emerging counter-culture responded to prohibition. The lobby group NORML would push for decriminalization – which essentially resulted in a type of punishment-switching that did not improve the situation for cannabis users – but during this decade 11 US States would adopt “decrim” regulations along with the appearance of progress. The other branch – the medical autonomy proponents best represented by the dissident writer Thomas Szasz – emerged. This autonomy was sometimes called for, but would have to wait for a future day to be realized.

Chapter 11 is about the 1980s, which mostly concerned the Reagans and their “Just Say No” drugwar nightmare. It also concerned Jack Herer, and his vision of a future hemp utopia, complete with an introduction to the science of hemp methanol/ethanol and how it could save the world from oil wars, oil spills and climate destabilization. His arguments about hemp saving the world began to spread amongst the pot community, creating an entirely new type of activist in the process.

Chapter 12, which covers the 1990s, is where this author makes his first appearance as a cannabis activist. It takes a close look at the impact of Marc Emery and his in-your-face entrepreneurial approach to cannabis activism. The vindication of hemp ethanol (in spite of Ed Rosenthal’s best efforts to dismiss it as a way to replace non-renewable energy) is also addressed in this chapter – in the November 1994 section – which is arguably the most valuable information in this entire series. Chapter 12 also examines Dennis Peron’s vital contribution to the med pot movement, which was in fact the beginning of the end of cannabis prohibition in North America.

Chapter 13, which involves the 2000s, begins with this author’s arguments at the Supreme Court of Canada, and explores what lessons could be learned from that experience. By the end of this decade, the movement had split into two groups – those who desired to create – or would tolerate the creation of – a cannabis cartel, and those who withstood all types of insults from their fellow pot activists in order to resist the creation of this cartel.

Chapter 14, which looks closely at the rise of the pot cartel, explains how the powers that be shifted from cannabis prohibition to models of pot distribution that allowed for a limited number of growers and distributors, what role the myth of cannabis psychosis played in that shift, and just who exactly in the pot movement was complicit in this horrible betrayal of humanity. This chapter looks closely at the efforts of Don Wirtshafter, arguably the most articulate and successful anti-cartel pot activist in the world, who helped to defeat the cartelists in his home state of Ohio.

Chapter 15 is an examination of the propaganda that accompanied the roll-out of pot legalization in Canada in 2018, along with an attempt at debunking all the fraudulent science underpinning that propaganda. Chapter 16 is a systematic examination of 50 studies concerning cannabis and mental illness – some of which attempt to argue that cannabis psychosis is a real thing, and some of which attempt to argue the contrary, but most of which avoid directly weighing in on the matter.

If one doesn’t approach examining the academic studies regarding cannabis and psychosis in a careful, systemic way, one might be led to believe that there must be an association of some kind – even a causal association – due to the sheer volume of material on the subject. After looking into the subject for decades, it is the conclusion of this author that there’s so much written about this topic because of what’s at stake – the freedom or the enslavement of humanity – not because a true causal connection actually exists.

One way we can confidently say that the concern over Reefer Madness has never been based upon science is that all of the most comprehensive studies of cannabis that have looked into the matter have debunked it. The Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report of 1893-1894, the LaGuardia Committee Report of 1944, the Wooton Report of 1968, the Le Dain Commission & The Shafer Commission of 1972, the Jamaican Study: Ganja In Jamaica of 1976, the Canadian Senate Report of 2002 – they all brought up evidence that long-term psychosis caused by cannabis use did not exist. Each of these reports brought the best science on the subject to light, and each of these reports were either dismissed with zero analysis or totally ignored by the prohibitionists who could not possibly attempt to address the evidence found within them.

The significance of the pro-pot revolt of the 1960s and 1970s should not be understated. It’s quite possible the entire world would be currently engulfed in a genocidal anti-pot pogrom similar to that which is currently happening in the Philippines today had it not been for the protests that began in the United States – in San Francisco – during the mid 1960s. From San Francisco it spread to New York, and then, slowly, to the rest of the world. Pro-pot messages in poems, songs, protest signs and a particularly powerful British newspaper advertisement led to opportunities for dissident scientists to conduct honest studies and issue progressive, high-profile reports. With diverging narratives in the straight and alternative media – and the dissident voices intruding into and getting louder within the straight media – the pressure was building to conduct scientific examinations afresh to determine once and for all time just how dangerous marijuana was.

The pot legalization movement (of the public protest variety) began in 1964, became prominent in the early 1970s, nearly disappeared in the 1980s but became high-profile again by the early 1990s onward. By 1968 the British had responded to these protests by issuing the Wooton Report, and by 1972, the Canadian and US government responded with final reports of Canada’s LeDain Commission and the US’s Shafer Commission. Instead of ever-increasing punishments, penalties were somewhat reduced in the 1970s, but with regards to any recommendation of punishment elimination, these reports were ignored by the powers-that-be. The protests had not eliminated prohibition, but had instead bought the pot community some time.

In the mid 1990s, the centre of the pot protest community drifted north from California to B.C., as Vancouver judges gave slaps on the wrist to pot seed sellers, and then Vancouver cops began to tolerate – or were put in the position of having to tolerate – pot smoking and growing and dealing at pot rallies. From Vancouver this tolerance for our community spread to other parts of Canada.

Canadian pot activists – this author included – took advantage of the “Rodney King-o-phobia” the cops sometimes displayed at protests (not wanting to be caught on camera using force without justification) and exploited it to demonstrate the actual amount of dignity and freedom the pot community was fighting for. Pot distribution at rallies soon transformed into pot selling clubs and weed retail storefronts and other types of drug-peace operations. This author was fortunate to have been one of the activists who created this new drug-peace beachhead, and the community I belonged to recorded and archived evidence of this beachhead for the rest of the world to learn from.

Meanwhile, the citizen’s initiative process which existed in roughly half of the States that made up the U.S. allowed for a type of pot-friendly direct democracy activism that wasn’t possible in referendum-resistant Canada. Medical marijuana initiatives were voted into law, beginning in California and Arizona in 1996, and the U.S. again took the global lead in cannabis activism, demonstrating what could be possible with the power of gathering signatures and the tenacity to define the “medicinal use” of marijuana in an all-encompassing manner.

More time passed, and the Canada Senate issued another comprehensive report on pot policy in 2002, which recommended total pot legalization and legal access for anyone 16 years or older. The report was of course ignored.

Slowly, the map of pot-friendly U.S. states expanded to include more and more initiative passing and med pot approval, and then recreational marijuana initiatives began being passed in 2012 in Colorado and Washington State. Nearly another generation went by, and finally the Canadian government decided to act. It created what the government (and the Canadian media) would call “legalization:” The Cannabis Act of 2018.

The Cannabis Act was designed to create a cartel for rich and well-connected producers. Ignoring all the major governmental reports from the last 130 years, focusing on some very biased studies (covered in Chapter 16) and bringing up various myths of inherent harm – especially cannabis psychosis. The Task Force brought together to advise the government on how to legalize pot created the justification needed to create tight regulations that would result in a very limited number of licensed producers.

These producers would lobby the Canadian government with promises of campaign contributions, which entrenched the new cartel. A similar form of entrenchment occurred on a state-by-state level in the US, with various forms of hard drug pot regulations resulting in a marijuana cartel there. Which brings us to today.

The cartel has persuaded many former pot activists to go along with the fiction that cannabis use makes kids stupid and/or crazy in order to justify the tight regulations required to limit the number of legal growers and dealers. Some of these activist/opportunists wished to take advantage of the captive market. Other activists just couldn’t be bothered to do any research and went with whichever narrative the mainstream media fed them.

Leaders of scapegoated communities are often presented a devil’s bargain: if they focus on saving the exceptions, the devil will focus on targeting the bulk of the group. In this case the rich producers and old users within the pot community – or perhaps a token non-white – were/are spared so long as most of the young, the non-whites and the poor remain(ed) targets for the police.

Hanna Arendt pointed to the same thing happening in the 1930s and 1940s with “exceptional Jews” being spared from Nazi persecution while the bulk of the Jews remained targets:

“Needless to say, the Nazis themselves never took these distinctions seriously, for them a Jew was a Jew, but the categories played a certain role up to the very end, since they helped put to rest a certain uneasiness among the German population: only Polish Jews were deported, only people who had shirked military service, and so on. For those who did not want to close their eyes it must have been clear from the beginning that it ‘was a general practice to allow certain exceptions in order to be able to maintain the general rule all the more easily’ (in the words of Louis de Jong in an illuminating article on ‘Jews and Non-Jews in Nazi-Occupied Holland’).” (12)

The only possible way this pot cartel can be dismantled is a concerted effort by a new generation of pot activists to transform hard drug pot regulations into soft drug regulations, in order to make the pot economy more inclusive. But there’s a lot of stigma to destigmatize, and a lot of bunk science to debunk. And most – not all but most – of the pot activist community is currently making the same mistake the Jewish community did back in the 1930s and 1940s – focusing on exceptions (fighting for a few non-whites to be some of the lucky few to have licenses rather than removing all caps on the number of licenses, or making sure the worst sentences are commuted rather than ending all arrests and all punishment).

Our rulers “allow certain exceptions in order to be able to maintain the general rule all the more easily” – so that few of us activists end up attacking the actual premise for the general rule. Pot activists currently engaged in tokenism are being irresponsible – they aren’t thinking it through. They don’t understand the astounding, humanity-saving potential of a truly inclusive regulatory weed regime. They’re being played by our rulers.

Image #8: “OIL VS. HEMP ETHANOL,” David Malmo-Levine & Bob High, 2018

This series will attempt to remove all the ubiquitous stigma that has amassed over the last 130 years or so, partly through a close examination of the facts surrounding the concept of cannabis psychosis, proving once and for all that the Reefer Madness of today is a manifestation of a 130-year-old unrelenting propaganda campaign in the service of power and greed rather than arising from an honest examination of the evidence over the last twenty years or so.

This work occasionally explores the true meaning of various cannabis-related or drug war-related terms. Etymology – the study of word origins – is key to understanding their actual applications, and realizing their true power.

For example, the etymology of the word “cannabis” is “fragrant cane” or “stinky stick.” (13) Research into the etymology of this word opens up that whole “Christ/Messiah/kannehbosm” can-of-worms discussed in some detail in Chapter 2.

The etymology of the word “drug” is most likely “dry wares” such as dried herbs. (14) If true, herb dealers are the true drug dealers, and pharmacists are the fake drug dealers. Reclaiming the word “drug” to mean “dried herb” is the first step in the destigmatization of the term “drug dealer.” Hopefully someday soon, the term drug dealer will carry about as much stigma as the terms car dealer or art dealer currently do – that is to say, no stigma at all.

The etymology of the word “stigma” itself is a mark that was cut or burned into the skin of enemies of the state, by the state. (15) Stigma is a sign of government disapproval. Sometimes it’s an attack on scapegoats. Public disapproval of actual harmful behaviour is not called stigma, it’s called well-deserved shame or something similar.

As Thomas Szasz pointed out in the 1970s, the origin of the words “pharmacology” and “pharmacopeia” is “pharmakos,” which means “scapegoat:”

“In ancient Greece, the person sacrificed as a scapegoat was called the pharmakos. The root of modern terms such as pharmacology and pharmacopeia is therefore not ‘medicine,’ ‘drug,’ and ‘poison,’ as most dictionaries erroneously state, but ‘scapegoat’! To be sure, after the practice of human sacrifice was abandoned in Greece, probably around the sixth century B.C., the word did come to mean ‘medicine,’ ‘drug,’ and ‘poison.’ Interestingly, in modern Albanian pharmak still means only ‘poison.’” (16)

Scapegoats were once used as medicine for a society – to get rid of its diseases and problems. Now medicines are used as scapegoats for a society – to control populations and justify protection rackets and cartels.

Szasz also pointed out that the etymology of the word “addiction” is “attraction” or “inclination” – it only became “compulsion” after the drug war began in the early 1900s. (17)

The etymology of the word “recreation” includes “refreshment or curing of a person” and “recovery from illness.” (18) Recreation isn’t the opposite of medicine, it’s actually a subset of medicine. It’s medicine to keep healthy people healthy.

The etymology of “euphoria” is “feeling healthy and comfortable” – suggesting that euphoria is our ideal state of being. (19)

The etymology of “psychosis” literally means “abnormal condition of the mind” and originally meant “a giving of life; animation” – it only became the more negative meaning of “mental affection or derangement” in the mid 1800s. (20)

And the etymology of “ecstasy” can be said to be feeling “out of one’s mind” or can be said to be “contemplating divine things.” (21) Which definition of ecstasy a person chooses to subscribe to is probably based on whether they want to rationalize kicking down the doors of harmless people, or want to create a world where having one’s door kicked down never happens to harmless people.

This series was written to help make a world where the doors of the harmless will no longer be kicked down.

Image #9: “The profits arising by hemp-seed are cloathing, food, fishing, shipping, pleasure, profit, justice, whipping.” The Praise Of Hemp Seed, Edward Allde for H. Gosson, London, 1620. Repository: Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC, USA.

This series was written so that everyone – regardless of which drug they choose to use – everyone on planet earth can one day look forward to going outside in a livable, stable climate, to growing old, to be free from poverty and state oppression and scapegoating of any kind, to be free to self-medicate against disease and discomfort with the most effective drugs available, to be free to grow and supply those drugs to themselves and to others, to be free to gain employment from herbal medicine gardening and hemp farming and all the spin-off industries, to be free to grow and/or sell all the botanical medicines, to be free to enjoy the simple pleasures in life, with the same freedom safeguarded for future generations.

A global, universal symbiotic relationship with cannabis for each and every human – no exceptions – is the key to that utopia. Every human deserves to be able to maximize their beneficial relationship with their co-evolutionary plant partner in whatever way they see fit: medical, industrial, nutritional, economic, sacramental, or any combination of these.

The next and most important step toward this utopia is for everyone on earth to know – without a shadow of a doubt – that Reefer Madness has always been – and is still to this day – a fraud.

Citations:

- 1) Giacomo Casanova, History of My Life, Volumes 1 & 2, Translated by Willard R. Trask, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore & London, written between 1789 & 1797, first published as early as 1822, this edition published in 1997, p. 159

- 2) Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, and Ralph Metzner, “Rationale of the Mexican Psychedelic Training Center”, from Utopiates, Richard Blum & Associates, Atherton Press, New York, 1965, p. 179

- 3) William F. Buckley Jr., quoted by Richard Cowan, quoted by Allen St. Pierre, “The Heritage Foundation: A Last Refuge For Reefer Madness?” OCTOBER 17, 2010

- 4) Mark Schauer Dublin, N.H., Chemical & Engineering News, Energy Problems May 3, 2004 | A version of this story appeared in Volume 82, Issue 18 https://cen.acs.org/articles/82/i18/Energy-problems.html

- 5) Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects, Ethan B Russo, Br J Pharmacol. 2011 Aug; 163(7): 1344–1364. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3165946/

- 6) “Percentage of American Labor Force in Agriculture,” Digital History: Agriculture https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=11&psid=3837

- 7) “Ag and Food Sectors and the Economy,” Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/ag-and-food-sectors-and-the-economy

- 8) “Rauschgiftbekämpfung [The Fight Against Drugs] in the Third Reich, itself a long-forgotten importation of American Prohibition wedded to Nazi racial hygiene and a police state apparatus ever-ready to invoke the ‘wholesome popular sentiment’ expressed in the National Socialist-realist aesthetic to legitimize and enforce the performance principle of German fascism.” “From ‘Rausch’ to Rebellion: Walter Benjamin’s On Hashish & The Aesthetic Dimensions of Prohibitionist Realism,” Scott J. Thompson, The Journal of Cognitive Liberties, Vol. 1, Issue No. 2 pages 21-42 (Spring/Summer 2000) © 2000 CENTER FOR COGNITIVE LIBERTY AND ETHICS https://www.cognitiveliberty.org/ccle1/2jcl/2JCL21.htm

- 9) “Gone to Pot – A Review of the Association between Cannabis and Psychosis,” Rajiv Radhakrishnan, Samuel T. Wilkinson, and Deepak Cyril D’Souza, Front Psychiatry. 2014; 5: 54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4033190/

- 10) “Use of high-potency cannabis was a strong predictor of psychotic disorder in Amsterdam, London, and Paris where high-potency cannabis was widely available, by contrast with sites such as Palermo where this type was not yet available. In the Netherlands, the THC content reaches up to 67% in Nederhasj and 22% in Nederwiet; in London, skunk-like cannabis (average THC of 14%) represents 94% of the street market whereas in countries like Italy, France, and Spain, herbal types of cannabis with THC content of less than 10% were still commonly used.” “The contribution of cannabis use to variation in the incidence of psychotic disorder across Europe (EU-GEI): a multicentre case-control study,” Marta Di Forti, PhD Diego Quattrone, MD Tom P Freeman, PhD Giada Tripoli, MSc Charlotte Gayer-Anderson, PhD Harriet Quigley, MD Victoria Rodriguez, MD Hannah E Jongsma, PhD Laura Ferraro, PhD Caterina La Cascia, PhD Prof Daniele La Barbera, MD Ilaria Tarricone, PhD Prof Domenico Berardi, MD Prof Andrei Szöke, PhD Prof Celso Arango, PhD Andrea Tortelli, PhD Eva Velthorst, PhD Prof Miguel Bernardo, PhD Cristina Marta Del-Ben, PhD Prof Paulo Rossi Menezes, PhD Prof Jean-Paul Selten, PhD Prof Peter B Jones, PhD James B Kirkbride, PhD Prof Bart PF Rutten, PhD Prof Lieuwe de Haan, PhD Prof Pak C Sham, PhD Prof Jim van Os, PhD Prof Cathryn M Lewis, PhD Prof Michael Lynskey, PhD Prof Craig Morgan, PhD Prof Robin M Murray, FRS theEU-GEI WP2 Group, The Lancet Psychiatry, VOLUME 6, ISSUE 5, P427-436, MAY 01, 2019 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(19)30048-3/fulltext

- 11) “Multiple reports indicate no rise in psychosis accompanies increases in pot use rates,” January 6, 2019, pot-facts.ca

Multiple reports indicate no rise in psychosis accompanies increases in pot use rates

“Even more evidence of ‘cannabis psychosis’ being a fraudulent scam.” May 28, 2022, pot-facts.ca

Even more evidence of “cannabis psychosis” being a fraudulent scam.

- 12) Hannah Arendt, Eichmann In Jerusalem: A Report On The Banality Of Evil, Viking Press, New York, 1963, p. 64 https://platypus1917.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/arendt_eichmanninjerusalem.pdf

- 13) “Both in the original Hebrew text of the Old Testament and in the Aramaic translation, the word ‘kaneh’ or ‘ keneh’ is used either alone or linked to the adjective bosm in Hebrew and busma in Aramaic, meaning aromatic.” SULA BENET, “EARLY DIFFUSION AND FOLK USES OF HEMP” from Rubin, Vera & Comitas, Lambros, (eds.), Cannabis and Culture, 1975, 39-49 https://www.קנאביס.com/wp-content/PDF/EARLY-DIFFUSION-AND-FOLK-USES-OF-HEMP-SULA-BENET.pdf

- 14) “drug (n.) late 14c., drogge (early 14c. in Anglo-French), ‘any substance used in the composition or preparation of medicines,’ from Old French droge ‘supply, stock, provision’ (14c.), which is of unknown origin. Perhaps it is from Middle Dutch or Middle Low German droge-vate ‘dry barrels,’ or droge waere, literally ‘dry wares’ (but specifically drugs and spices), with first element mistaken as indicating the contents, or because medicines mostly consisted of dried herbs.” https://www.etymonline.com/word/drug

- 15) “Stigma (plural, stigmata) is a Greek word that in its origins referred to a kind of tattoo mark that was cut or burned into the skin of criminals, slaves, or traitors in order to visibly identify them as blemished or morally polluted persons.” https://www.encyclopedia.com/plants-and-animals/botany/botany-general/stigma

- 16) Thomas Szasz, Ceremonial Chemistry, Anchor Press/Doubleday, Garden City, New York, 1974, p. 19

- 17) “addiction (n.) Origin and meaning of addiction c. 1600, ‘tendency, inclination, penchant’ (a less severe sense now obsolete); 1640s as ‘state of being (self)-addicted’ to a habit, pursuit, etc., from Latin addictionem (nominative addictio) ‘an awarding, a delivering up,’ noun of action from past-participle stem of addicere ‘to deliver, award; devote, consecrate, sacrifice’ (see addict (v.)). In the sense ‘compulsion and need to take a drug as a result of prior use of it’ from 1906, in reference to opium (there is an isolated instance from 1779 with reference to tobacco).” https://www.etymonline.com/word/addiction

- 18) “recreation (n.) late 14c., recreacioun, ‘refreshment or curing of a person, refreshment by eating,’ from Old French recreacion (13c.), from Latin recreationem (nominative recreatio) ‘recovery from illness,’ noun of action from past participle stem of recreare ‘to refresh, restore, make anew, revive, invigorate,’ from re- ‘again’ (see re-) + creare ‘create’ (from PIE root *ker- (2) ‘to grow’). Meaning ‘refresh oneself by some amusement’ is first recorded c. 1400.” https://www.etymonline.com/word/recreation

- 19) “euphoria (n.) 1727, a physician’s term for ‘condition of feeling healthy and comfortable (especially when sick),’ medical Latin, from Greek euphoria ‘power of enduring easily,’ from euphoros, literally ‘bearing well,’ from eu ‘well’ (see eu-) + pherein ‘to carry,’ from PIE root *bher- (1) ‘to carry.’ Non-technical use, now the main one, dates to 1882 and perhaps is a reintroduction. Earlier the word meant ‘effective operation of a medicine on a patient’ (1680s).” https://www.etymonline.com/word/euphoria

- 20) “psychosis (n.) updated on January 20, 2021 1847, ‘mental affection or derangement,’ Modern Latin, from Greek psykhē ‘mind, life, soul’ (see psyche) + -osis ‘abnormal condition.’ Greek psykhosis meant ‘a giving of life; animation; principle of life.’” https://www.etymonline.com/word/psychosis

- 21) “ecstasy (n.) late 14c., extasie ‘elation,’ from Old French estaise ‘ecstasy, rapture,’ from Late Latin extasis, from Greek ekstasis ‘entrancement, astonishment, insanity; any displacement or removal from the proper place,’ in New Testament ‘a trance,’ from existanai ‘displace, put out of place,’ also ‘drive out of one’s mind’ (existanai phrenon), from ek ‘out’ (see ex-) + histanai ‘to place, cause to stand,’ from PIE root *sta- ‘to stand, make or be firm.’ Used by 17c. mystical writers for ‘a state of rapture that stupefied the body while the soul contemplated divine things,’ which probably helped the meaning shift to ‘exalted state of good feeling’ (1610s). Slang use for the drug 3,4-methylendioxymethamphetamine dates from 1985. Formerly also spelled ecstasie, extacy, extasy, etc. Attempts to coin a verb to go with it include ecstasy (1620s), ecstatize (1650s), ecstasiate (1823), ecstasize (1830).” https://www.etymonline.com/word/ecstasy