Traditional Medicine Part 3: Ayahuasca

CANNABIS CULTURE – An ongoing series from Cannabis Culture regarding the applicability of UNDRIP “traditional medicine” rights of Indigenous people to the use and the economies of psychoactive and psychedelic plant drugs.

Part 1 was all about cannabis.

Part 2 looked closer at the United Nations UNDRIP treaty and at the concept of Biopiracy.

Part 3 will look at the magical brew that is becoming more and more popular amongst settler psychonauts with each passing year: ayahuasca.

Image #1: Sydtomcat https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ayahuasca_Visuals.png

“The medicine men prefer to make their intoxicating caapi drink from old lianas (vines) growing in the jungle. These, however, are getting scarce, and many of the practitioners cultivate the plant in their coca gardens. It is not difficult to cultivate from cuttings. The psychic effects of the ‘vine of the soul’ differ sometimes strikingly, according to the environmental and ceremonial background against which it is taken; the additives, if any, that are used in its preparation, the amount of the drug imbibed, the strength of the auto-suggestion on the part of the Indian and numerous other factors. There are, however, certain effects which seem to be constant: visions in dull blue and gray; but when certain additives are used, brilliant colours are experienced. Everything appears larger than in real life (macropsia): multitudes of people or animals, often snakes of many colours, and jaguars, dangerous waterfalls or enormous mountains veiled in multicoloured mist or clouds are seen. Very frequently, auditory effects are experienced, especially if chanting or instrumental music is loud. The show of bravado sometimes exhibited at the start of the intoxication does not appear to be common; erotic aspects often reported may be due to the individual personality differences of the participants. Some payés (medicine men) maintain that with the help of the drug they can cause frightening eclipses of the moon, call down tornadoes or control the weather during caapi intoxication. Muscular incoordination is rarely experienced; in fact, this intoxicant is taken very frequently during dance ceremonies. The beverage is extremely, sometimes nauseatingly, bitter and vomiting usually accompanies the first draught. It almost always causes diarrhea.”

- Richard Evans Schultes, & Robert F. Raffauf, Vine of the Soul, 2004 (1)

Image #2: https://mellowist.com/products/ayahuasca-11×17-art-print

The word “Ayahuasca” (meaning “the vine of the spirits”) (2) is the Spanish term for a brew normally made with

a) the vine (“liana”) of Banisteriopsis caapi, (“B. caapi” – also known as yajé or yagé – pronounced “yah-hey”) which is a “monoamine oxidase inhibitor” (MAOI – which the first synthetic antidepressants were based on), (3) and

b) at least one other DMT-containing plant (of which there are many – stay tuned for a future article about DMT-containing plants),

turning a normally orally-inactive and short-duration smoked or vaped 5-minute DMT high into a four-hour DMT trip you can drink. Users often report vomiting along with intense hallucinations or visions. (4) Sometimes Syrian rue seeds are used in the place of Banisteriopsis caapi in less-traditional Ayahuasca mixtures. (5)

Image #3: Preparation of Ayahuasca, Province of Pastaza, Ecuador https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ayahuasca

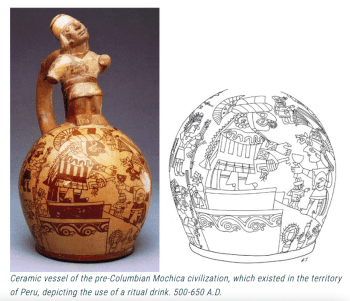

Image #4: “The oldest archaeological find with traces of a ritual drink similar to modern Ayahuasca brew is a ceremonial goblet found in Ecuador, believed to be over 2,500 years old.” https://uniraolodge.com/en/news/blessed-by-pacha-mama-herself/

Ancient Use:

Evidence of the Use of Ayahuasca dates back at least 1000 years, arising from an archeological find from a cave in Bolivia back in 2010. (6)

Image #5: https://www.businessinsider.com/ayahuasca-cocaine-shaman-drug-pouch-found-in-andes-2019-5

Image #6: https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/667003

Early Historical Record:

The introduction of ayahuasca to settlers by Indigenous people is well-documented. The first known contact between ayahuasca users and a European was in 1675. This incident was collected in a series of encounters and compiled by historian José Chantre y Herrera in the 1700s. The priests who first took note of ayahuasca made observations but did not sample this particular sacrament.

According to modern-day researchers the “object of his history was to present the Jesuit mission in the most heroic light” and “Indigenous people are described as liars and sorcerers.” This first account focuses on what “the diviner” is chanting, and made no mention of psychedelic effects. (7) Another report of ayahuasca occurred in 1737 by a Jesuit priest named Pablo Maroni, who described “an intoxicating potion ingested for divinatory and other purposes and called ayahuasca, which deprives one of his senses and, at times, of his life.” (8)

A plant called “hayachuasca” was identified by a catholic priest named Father Veigl back in 1798, but only as a plant involved in “superstitious practices and witchcraft” that put the user “into a prolonged state of complete unconsciousness” – not as an entheogen that put the user into a state of hyperconsciousness. (9) It was probably a combination of a) being part of a religion (Christianity) that had long forsaken sacraments with actual psychoactive ingredients (10) and b) the Indigenous people regarding Catholic priests with a healthy dose of suspicion – noticing both the actual power-tripping intentions of these priests and the Catholic Church’s inability to comprehend the significance and relevance of entheogens – that prevented Veigl from understanding the actual significance of the brew. (11)

Image #7: Richard Spruce, from Richard Evans Schultes “RICHARD SPRUCE, AN EARLY ETHNOBOTANIST AND EXPLORER OF THE NORTHWEST AMAZON AND NORTHERN ANDES,” J. Ethnobiol. 3(2):139-147, December 1983, p. 140 https://ethnobiology.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/JoE/3-2/Schultes1983.pdf

British botanist Richard Spruce was the first European to identify yajé as an actual hallucinogen – he did so in 1851 or 1852, but his report wasn’t published until 1908. Spruce actually drank the brew, and reported back what he had seen:

“White men who have partaken of caapi in the proper way concur in their account of their sensations under its influence. They feel alternations of cold and heat, fear and boldness. The sight is disturbed, and visions pass rapidly before the eyes, wherein everything gorgeous and magnificent they have heard or read of seems combined; and presently the scene changes to things uncouth and horrible.” (12)

Ecuadorian Geographer Manuel Villavicencio described drinking ayahuasca in the first published report of the drug in 1858. (13)

Image #8: “Cammino del Napo” (Napo Road) “Subida de Guacamayos” (Macaw Climb), Villavicencio, M. (1858). Geografía de la República del Ecuador. New York: R. Craighead, p. 366 https://garystockbridge617.getarchive.net/media/villavicencio1858-p366-camino-del-napo-f47558

Further publicity to Ayahuasca came from the German pharmacologist Louis Lewin’s Phantastica (first published in German 1924) (14) and William S. Burroughs & Allen Ginsberg’s short book The Yage Letters (published in 1963) (15) as well as various academic articles written by Richard Evans Schultes in the 1950s and 1960s. (16)

Image #9: “William Burroughs under the lens of ethnobotanist Dr. Richard Schultes in Mocoa, Colombia, 1953. Burroughs holds an ayahuasca vine” https://www.infobae.com/america/cultura-america/2018/02/05/la-psicodelica-aventura-de-william-s-burroughs-por-sudamerica/

Image #10: Photo of an associate of Dr. Richard Schultes, taken by Schultes, in the same place as image #9, in 1953. Vine Of The Soul, Schultes & Raffauf, p. 30

Interestingly, Burroughs and Schultes actually met in early 1953 in southern Columbia, when Burroughs was in search of “yage” (sic) – what he called “the final fix” in the last sentence of his 1953 book Junky. Burroughs called Schultes “Doc Schindler” in The Yage Letters.

Burroughs scored “a wineglass full” of ayahuasca, vomited and had crazy visions, then compared notes with Schultes on what effects they had both experienced from the powerful brew. Wade Davis recounts this discussion in his book One River:

“‘I never get sick,’ Schultes told him. Burroughs mentioned that at one point he felt himself change into a black woman, then a black man, then a man and a woman at the same time, with everything writhing as in a Van Gogh painting. He had achieved pure bisexuality, becoming a man or woman at will, awash with wild convulsions of lust. ‘I only get colors, no visions,’ Schultes replied.” (17)

Image #11: Schultes with Makuna boys, during a yagé ceremony. Apaporis: Workshop of the Gods https://www.amazonteam.org/maps/schultes/en/

Image #12: Drawings on a maloca representing yage visions. Sacred Plants of the Putumayo https://www.amazonteam.org/maps/schultes/en/

Image #12: Drawings on a maloca representing yage visions. Sacred Plants of the Putumayo https://www.amazonteam.org/maps/schultes/en/

Current Traditional Use:

Use of ayahuasca differs depending on which one of a variety of traditions is chosen. Like some magic mushroom rituals, sometimes the healer takes the medicine as a method of gaining insight into the condition of the sick person. Sometimes the sick person themselves takes the medicine. Sometimes there’s a spiritual context. And sometimes use is recreational:

“On a trip up the Purus River in 1968, the scientists Jan-Erik Lindgren and Laurent Rivier noted that in most of the Pano-speaking indigenous communities they visited, only healers consumed the brew to interface with a spiritual plane of existence, to figure out the metaphysical causes of, and to help resolve, patients’ illnesses. But in two communities, one Pano-speaking, one non-Pano-speaking, average men (and very rarely women) just drank ayahuasca together in casual settings, with little ritual, to bond socially through their visionary experiences.” (18)

Today, in Iquitos, Peru (one of the current centers of ayahuasca culture), on any given Friday night 50,000 people could be involved in one of the many ayahuasca ceremonies scattered around the city of a half-million people. (19)

Image #13: “Illustration of an Ayahuasca visual by Pablo Amaringo via Flickr” https://daily.jstor.org/the-colonization-of-the-ayahuasca-experience/

Current Medical Applications:

According to Wikipedia, ayahuasca has potential antidepressant, anti-anxiety, and anti-addiction effects:

“There are potential antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of ayahuasca. For example, in 2018 it was reported that a single dose of ayahuasca significantly reduced symptoms of treatment-resistant depression in a small placebo-controlled trial. More specifically, statistically significant reductions of up to 82% in depressive scores were observed between baseline and 1, 7 and 21 days after ayahuasca administration, as measured on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and the Anxious-Depression subscale of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Other placebo-controlled research has provided evidence that ayahuasca can help improve self-perceptions in those with social anxiety disorder. Ayahuasca has also been studied for the treatment of addictions and shown to be effective, with lower Addiction Severity Index scores seen in users of ayahuasca compared to controls. Ayahuasca users have also been seen to consume less alcohol.” (20)

Image #14: https://www.choosehelp.com/topics/complementary-alternative-therapies/shamanic-visions-to-cure-your-addiction-an-overview-of-ayahuasca-as-an-addiction-treatment

Ayahuasca can also help a person understand “their purpose on earth, the true nature of the universe and insight into how to be the best person they possibly can.” (21)

Safety Profiles:

According to the user guide from the Coca Leaf Café & Mushroom Dispensary that I work at:

“Vomiting, diarrhea and hot/cold flashes can follow the use of ayahuasca, which can complicate certain medical conditions. Use can also cause significant but temporary emotional and psychological distress. Use along with SSRIs can cause serotonin syndrome. Do not mix with SSRIs, SNRIs, lithium, anti-psychotics, stimulants, depressants, or any other recreational drug aside from maybe cannabis. Avoid tyramine-rich foods such as aged cheese, processed or cured meat, pocked or fermented foods, soy, tofu, beer, wine, or citrus fruits for 48 hours before or 24 hours after consuming ayahuasca. Use only in a safe environment. Avoid risky activities.” (22)

Image #15: Taken by this author at the Coca Leaf Café – 651 East Hastings St., Vancouver, B.C.

Image #16: Taken by this author at the Coca Leaf Café – 651 East Hastings St., Vancouver, B.C.

Image #17: Taken by this author at the Coca Leaf Café – 651 East Hastings St., Vancouver, B.C.

Image #18: Taken by this author at the Coca Leaf Café – 651 East Hastings St., Vancouver, B.C.

Avoid mixing Ayahuasca with 5-MeO-DMT – it can have “lethal consequences”. (23)

Wikipedia has summarized the risks this way:

“Depending on dosage, the temporary non-entheogenic effects of ayahuasca can include tremors, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, autonomic instability, hyperthermia, sweating, motor function impairment, sedation, relaxation, vertigo, dizziness, and muscle spasms which are primarily caused by the harmala alkaloids in ayahuasca. Long-term negative effects are not known. A few deaths linked to participation in the consumption of ayahuasca have been reported. Some of the deaths may have been due to unscreened preexisting cardiovascular conditions, interaction with drugs, such as antidepressants, recreational drugs, caffeine (due to the CYP1A2 inhibition of the harmala alkaloids), nicotine (from drinking tobacco tea for purging/cleansing), or from improper/irresponsible use due to behavioral risks or possible drug to drug interactions.” (24)

The main danger of ayahuasca seems to be charlatan facilitators who have no training in recognizing health problems and/or applying first-aid, and/or who provide drug mixes that are contraindicated (that don’t mix well together) and/or provide drugs of dubious quality. For example, there was a death at an ayahuasca ceremony in Australia in 2021:

“Participants in an ayahuasca ceremony at a six-day retreat were instructed by so-called ‘guardians’ to keep their eyes fixed towards the shaman conducting the ritual and away from the man dying metres away from them, a coroner has heard. The fourth day of the inquest into the death of Jarrad Antonovich, being held in Lismore, heard from several participants in the ceremony at the Dreaming arts festival near Kyogle, in northern New South Wales, on 16 October 2021. Among them was a Byron Bay dentist, Marcus O’Meara, who spoke of a group of people called the guardians who were inside the ‘gonpa’ – or temple – in which the ceremony was being held and were tasked with ‘keeping an eye on everybody’. In the centre of the gonpa was the man who was presiding over the festival and the evening, a self-described clairvoyant and convener of sacred music ceremonies, Soulore ‘Lore’ Solaris, the inquest heard. The inquest has heard Antonovich died after consuming ayahuasca – made from Amazonian plants – and being administered ‘kambo’ frog toxins during the retreat.” (25)

Image #19: “Kambo inquest hears Jarrad Antonovich’s death was described as a ‘beautiful occasion’,” ABC North Coast / Bruce MacKenzie, 10 May 2023 https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-05-10/kambo-frog-poison-inquest-hears-death-was-described-as-beautiful/102327808

It is unknown whether the death was a direct result of the kambo frog toxin itself – which has known to be lethal – or if it involved a bad drug interaction and/or a previous injury. (26) It could very well be that some facilitators have priorities other than the safety of their charges in mind during their ceremonies – priorities such as the appearance of an “authentic” traditional ayahuasca experience and/or maintaining a belief in their egotistical hocus-pocus bullshit:

“Dr Dwyer also told the court that the ambulance officers who arrived at the scene noticed 10 to 20 people in the same space who were ‘preoccupied with the ceremony’ that was taking place, and someone in the room asked the paramedics ‘move away from Jarred because they were interfering with his aura’.” (27)

Image #20: “Energetic and Metaphysical Healing These sessions facilitate energy movement and flow that restore clarity in the emotional and auric fields of the body. Using metaphysical and psychic abilities Lore is able clear and cleanse energy fields removing emotional and psychic wounds, working with forces of nature, spirit guides and ancestors, to reconnect, integrate and strengthen health and conscious awareness through the body and mind.” – From the website of Soulore (Lore) Solaris

https://dreamingarts.net/healing/

It seems that – from the perspective of this author – those who claim to be able to read auras should be required to provide credible proof of this claim from now on, or else any other of their health or safety-related claims should be considered suspect.

Another problem that has gotten attention lately is the predator shaman – a “healer” who sexually assaults women when they are tripping and less able to understand what is happening or resist. (28) Due to how common a complaint this has become (one can find predator healers in all types of psychedelic “healing” communities), it is probably a good idea to insist on tripping with friends and/or videotaping the ceremony to prevent these types of “healers” from betraying the trust people put in them.

Legal Status:

Extracted DMT is a controlled drug under the international treaties – but plants, preparations and decoctions containing DMT are not subject to international control. National controls are a different story. There are varying differences in the way ayahuasca is treated from nation to nation, both in its official status and its treatment by various levels of law enforcement. (29) Globally, at least 31 people have been arrested for ayahuasca – most of them recently – according to the Ayahuasca Defense Fund. (30)

Image #21: https://www.tampabay.com/news/courts/criminal/He-called-it-a-hair-tonic-feds-called-it-illegal-but-the-name-is-ayahuasca-_169602140/

Image #22: https://www.mentalhealthdisparities.org/psychedelics-spirituality.php

In June of 2017, the Santo Daime Church of Montreal, Canada was granted the right to import ayahuasca and serve it in their rituals. (31) One white American woman – Tina ‘Kat’ Courtney – who was arrested for ayahuasca possession in 2022 managed to transform her arrest into street cred for her plant medicine company. (32)

Image #23: https://www.listennotes.com/podcasts/a-womans-blessing/07-tina-kat-courtney-on-61bXrIOz9cM/

Biopiracy Activity:

The history of ayahuasca biopiracy provides a perfect example of the glaring injustice provided for the benefit of white people at the expense of Indigenous people. In the early 1980s, a variety of ayahuasca “was discovered growing in a domestic garden in the Amazon rain-forest of South America” according to the world’s first ayahuasca patent. (33) This “discovered in a garden” claim within the patent was “apparently not true” according to researchers. (34)

Dr. Kenneth Tupper – a researcher who specializes in psychedelics – summarized the notorious case of this 1986 “Da Vine” plant patent:

“In November 1984, an American named Loren Miller filed for a patent on a ‘new and distinct’ B. caapi vine that he had named ‘Da Vine’ – the claim to novelty was based on ‘the rose color of its flower petals which fade with age to near white, and its medicinal properties’ (Miller 1984). The United States Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) issued the patent in June 1986. When South American indigenous peoples learned that one of their most sacred medicinal plants had been patented, they sought redress with the help of the Centre for International Environmental Law (CIEL). On behalf of the Coordinating Body of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA) and the Coalition for Amazonian Peoples and their Environment (Amazon Coalition), CIEL formally filed a request to the PTO for re-examination of the ‘ayahuasca patent’ in March 1999 (Centre for International Environmental Law 1999). The CIEL request argued that the ‘Da Vine’ patent should be rescinded for failing to meet several requirements of the US Plant Patent Act. Specifically, it charged that ‘Da Vine’ was neither distinct nor new, that it was found in an uncultivated state and that its patenting violated the public policy and morality aspects of the Plant Patent Act (Centre for International Environmental Law 1999). In November 1999, the PTO revoked Miller’s patent, but only on the grounds that the so-called invention had been previously described; they refused to consider the issues of whether traditional indigenous knowledge of a plant or its uses should be considered ‘prior art’ or whether the patent violated the Plant Patent Act’s public policy and morality conditions (Wiser 1999). Subsequently, Miller exercised his right to appeal against the PTO’s rejection and, in January 2001, without allowance for any further consideration of opposing views, the PTO reversed its decision, reinstated the ‘Da Vine’ patent, and closed the file (Wiser 2001). The Amazonian indigenous peoples who initially sought the rejection were understandably outraged, but had no further legal recourse. For Miller, the final decision was a symbolic victory rather than a material one, as the life span of the original patent was 17 years; in June 2003 it expired and cannot be renewed (Centre for International Environmental Law 2003). For indigenous peoples, however, in this specific case and more generally, the decision was a symbolic loss. The PTO reasserted the privileged authority of Eurocentric views of knowledge and property, effectively denying both the spiritual value of the ayahuasca vine for Amazonian indigenous peoples and the legitimacy (or even recognition) of prior art in their ceremonial and oral traditions.” (35)

Image #24: https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/a7/b6/d4/2db4c56b110116/USPP5751.pdf

A careful look at the 1986 Da Vine patent reveals that it claims that the patent holder – Loren Miller – was the first person to “discover” B. caapi with “rose colored” flowers:

“The instant plant presents flower petals which are rose colored fading to white with age. The instant plant may be distinguished from the species per se in flower color, B. cappi having pale pink flowers fading to pale yellow.” (36)

According to Schultes and Hofmann in their popular and well-circulated book Plants of the Gods (first published in 1979 – 5 years before Miller applied for his “Da Vine” patent), rose-colored flowers were already a known species. (37) Rose-colored flowers were also found in herbarium specimens – submitted the year before Miller first applied for his “Da Vine” patent. (38) Basically, Miller lied about finding cultivated B. caapi and then lied again when he claimed it was a yet-to-be discovered/academically recognized variety – and he got away with it.

Image #25: https://twitter.com/JocelynBosse/status/1406944990815830017

Researchers have noted the “ironic twist” involved with a system that allows privileged white people with a rudimentary understanding of the plant patent process to patent plant medicines while other people – often non-white – get arrested for possessing the very same plants:

“Incidental to the impacts of current drug policy on indigenous peoples, plants and combinations of plants used by shamans, healers, and other traditional knowledge holders are often the subject of interest by outside commercial interests. In an ironic twist of the prevailing drug regime, indigenous peoples criminalized for the use of certain psychoactive drugs for community use may lose intellectual property rights to their inventions. This occurred with ayahuasca, a psychoactive plant-based product used by Amazonian indigenous peoples for spiritual and healing for which a US patent was requested in 1986 and affirmed in 2001.” (39)

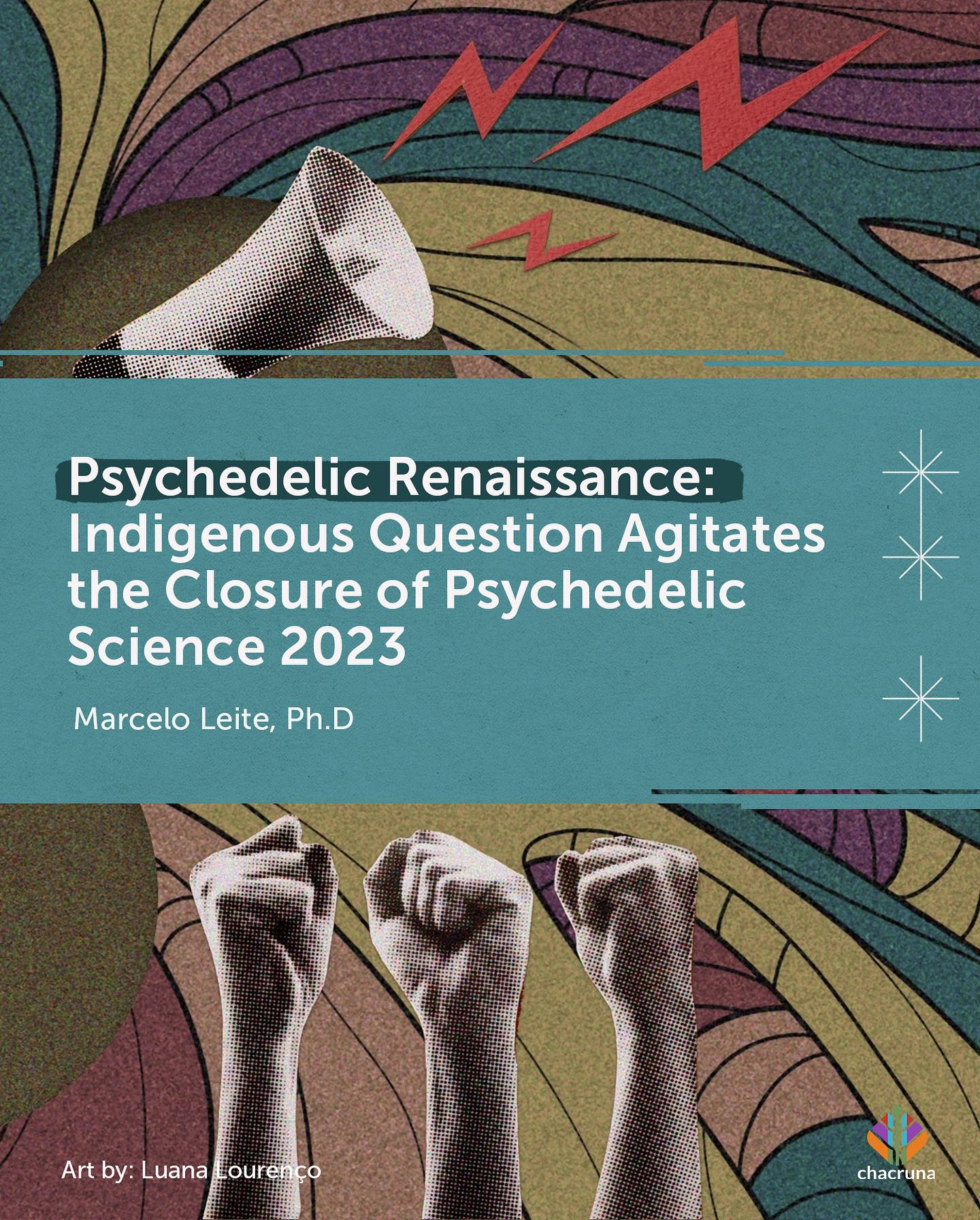

Image #26: https://psychedelichealth.co.uk/2023/06/21/psychedelic-science-puts-indigenous-medicine-conservation-in-spotlight/

As noted in citation #120 of part 1, Indigenous people of the “New World” (new to Europeans, anyway) have had a long tradition of sharing medical knowledge with each other rather than creating exclusive medical relationships and doctor-patient dynamics. Thus, as Vice.com noted a few years ago, many of those who live in the ayahuasca community seem more ready to share ayahuasca and welcome outsiders into the economy than members of the plant patent community do:

“‘Being Amazonian is not any warranty that the person in question is qualified or has good intentions,’ said Luis Eduardo Luna, an anthropologist and ayahuasca researcher who was born in the Colombian Amazon. ‘Conversely, being non-Amazonian, from any region or country, does not mean that the person is doing sessions mainly for financial gain. In our global world, anybody can learn anything and be able to teach it to others.’” (40)

But the obvious danger of welcoming outsiders is that some of them lack the necessary training and vetting needed to avoid charlatanism – as Vice.com noted a decade ago:

“It used to be that it took about at least 20 years to apprentice as a shaman, and now there are people claiming they are shamans within two or three years. There’s no quality control—there’s no knowledge of lineage—so Westerners go online, see ‘Amazonian retreats,’ and it doesn’t even occur to them to enquire who the shaman is, what his lineage is, whether he has recommendations . . . It seems to be a Disneyland mentality. It’s a set-up for disaster, because with all these naive people bringing money in, there’s an explosion of people setting up centers, making brews of different levels of quality. People are going to keep dying as long as this goes on.” (41)

Image #27: https://psychedelichealth.co.uk/2023/06/21/psychedelic-science-puts-indigenous-medicine-conservation-in-spotlight/

Image #28: https://www.facebook.com/chacruna.institute/

Some Indigenous communities have even faced settlers murdering their healers for not revealing secrets, as well as a relocation of their healers and teachers closer to tourist areas, to the detriment of local communities, and have taken steps to remedy these problems by attempting to protect and strengthen their local ayahuasca culture. (42)

Ayahuasca researcher Ken Tupper draws attention to the debate within the ayahuasca community regarding outsider participation:

“There exist a variety of indigenous attitudes towards nonindigenous interest in their spiritual traditions; for example:

[some] say that Native American religious practices are crucial if the world is to be preserved. Some believe that it is only pure, uninfluenced native ceremony that can preserve the world. But a significant minority argue that non-Indian participation in ‘the red road’ is necessary if humans are to reharmonize life on earth. (Taylor 1997: 187, italics in original)

McGaa, an Oglala Sioux author, makes a similar case, namely that allowing nonindigenous participation in native ritual is a crucial step towards promoting an indigenous ecological cosmovision. As he (1990: vii) puts it, ‘if the Native Americans keep all their spirituality within their own community, the old wisdom that has performed so well will not be allowed to work its environmental medicine on the world where it is desperately needed.’ Luna (2003), writing as a contemporary neoayahuasquero, argues that contemporary non-indigenous medicinal and sacramental uses of ayahuasca represent evolving traditions of spiritual awakening.” (43)

Image #29: https://www.facebook.com/chacruna.institute/

The lessons learned from the history of ayahuasca biopiracy are 1) settlers will lie on their patent applications to make a fast buck, and 2) in spite of a totally greasy plant patent application, harm to local communities from ayahuasca tourism and some sketchy-as-f settler “shamans” preying on the vulnerable or putting people’s lives at risk, some Indigenous people are still prepared to share the ayahuasca economy with outsiders – provided we learn from our mistakes, respect the medicine, avoid harvesting old-growth plant sources to extinction, fairly compensate the farmers who provide it, and encourage proper cultivation, distribution and use.

Stay tuned to Cannabis Culture for the next stop on our tour of Indigenous traditional medicines: blue lotus and red lotus.

Citations:

1. Richard Evans Schultes, & Robert F. Raffauf, Vine of the Soul, Synergetic Press, New Mexico, 2004, p. 24

2. “‘My Father and My Mother, Show Me Your Beauty’: Ritual Use of Ayahuasca in Rio de Janeiro,” Tania Soibelman, Fall 1995

http://www.neip.info/novo/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/MyFatherandMyMotherShowMeYourBeautyRitualUseofAyahuascainRiodeJaneiro.pdf

3. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/maois/art-20043992

4. caapi is native to Argentina Northwest, Bolivia, Brazil North, Brazil West-Central, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. Banisteriopsis caapi (Spruce ex Griseb.) C.V.Morton First published in J. Washington Acad. Sci. 21: 486 (1931) https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:29180-2

5. https://erowid.org/chemicals/ayahuasca/ayahuasca.shtml

6. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ayahuasca

7. “Ancient hallucinogens found in 1,000-year-old shamanic pouch – The ritual container, made of three fox snouts, contains the earliest known evidence of ayahuasca preparation.” BYERIN BLAKEMORE, MAY 6, 2019

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/ancient-hallucinogens-oldest-ayahuasca-found-shaman-pouch

“Our results indicate that this is the largest number of psychoactive compounds found in association with a single archaeological artifact from South America. The chemical residues of at least five compounds that are known to have psychotropic effects on humans, present in the fox-snout pouch, imply that multiple plants were used to induce extraordinary states of consciousness, potentially within a range of ritual and healing contexts. The plants that were used in the rituals included Erythroxylum, Anadenanthera, Banisteriopsis, and potentially other sources contributing DMT and psilocin (such as Psychotria leaves and hallucinogenic fungi). This is conclusive evidence for the presence of at least three psychoactive plants, the highest number of such specimens recovered from a single South American artifact, and suggests intriguing evidence that ritual specialists might have manipulated and used multiple plants together in their psychoactive preparations.”

“Chemical evidence for the use of multiple psychotropic plants in a 1,000-year-old ritual bundle from South America,” Melanie J. Miller, Juan Albarracin-Jordan, Christine Moore, and José M. Capriles, Universidad Nacional Autonóma de México, Mexico, D.F., Mexico, May 6, 2019

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1902174116

8. 1648-1768 – The First Written Reports of Ayahuasca Made by Jesuit Missionaries https://ayahuasca-timeline.kahpi.net/ayahuasca-first-reports-jesuit-missionaries/

9. Ibid.

10. “Of the plants worth mentioning, it is necessary to mention in the first place the hayachuasca, which means, ‘bitter rope,’ and is used only for superstitious practices and witchcraft. This plant is in the form of a ribbon, like the bark of the tallest tree. The Indians, taking the concoction prepared with I don’t know what ritual, fall into a prolonged state of complete unconsciousness.”

Franz Xavier Veigl, Noticias detalladas sobre el estado de la Provincia de Maynas en América meridional hasta el año de 1768, (Iquitos, 1798), p. 180.

11. Sex, Drugs, Violence and the Bible, Chris Bennett & Neil McQueen, Forbidden Fruit Publishing Company, Gibsons, B.C., 2001, pp. 161-208

12. “Investigating a Century-Long Hole in History: The Untold Story of Ayahuasca From 1755-1865,” Justin Williams, Department of History, University of Colorado at Boulder, May 2015

13. “Notes of a botanist on the Amazon & Andes: being records of travel on the Amazon and its tributaries, the Trombetas, Rio Negro, Uaupés, Casiquiari, Pacimoni, Huallaga and Pastasa; as also to the cataracts of the Orinoco, along the eastern side of the Andes of Peru and Ecuador, and the shores of the Pacific, during the years 1849-1864,” Spruce, Richard, 1817-1893, Publication date 1908, p. 420

https://archive.org/details/b31360117_0004/page/419/mode/1up?view=theater

14. Geografía de la República del Ecuador, Villavicencio, Manuel, 1858, pp. 371-372

https://access.bl.uk/item/viewer/ark:/81055/vdc_0000000129C6#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&xywh=-1797%2C-149%2C5223%2C2966

See also:

https://archive.org/details/geografiadelare00villgoog/page/372/mode/2up

Richard Evans Schultes, Hallucinogenic Plants – A Golden Guide, 1976, Golden Press, New York, p. 100

See also:

Richard Evans Schultes, “Hallucinogenic Plants of the New World,” Summer 1963, The Harvard Review, Vol. 1, #4, p. 20

1858 – Ecuadorian Geographer Manuel Villavicencio Describes Drinking Ayahuasca https://ayahuasca-timeline.kahpi.net/manuel-villavicencio-ayahuasca/

15. Phantastica narcotic and stimulating drugs, their use and abuse. by Lewin, Louis, 1924, Inner Traditions/Park St. Press edition, Rochester, Vermont, 1998, p. 116 https://openlibrary.org/books/OL5930086M/Phantastica

16. The yage letters, William S. Burroughs, City Lights Books, San Francisco, 1963/1975 https://archive.org/details/yageletters00burr https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Yage_Letters “The psychedelic adventure of William S. Burroughs through South America,” John Battle, Feb. 5, 2018 https://www.infobae.com/ichmon/cultura-america/2018/02/05/la-psicodelica-aventura-de-william-s-burroughs-por-sudamerica/

17. THE IDENTITY OF THE MALPIGHIACEOUS NARCOTICS OF SOUTH AMERICA Richard Evans Schultes Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University Vol. 18, No. 1 (June 7, 1957), pp. 1-56 (54 pages) Published By: Harvard University Herbaria https://www.jstor.org/stable/41762183

Hallucinogenic Plants of the New World, Richard Evans Schultes, The Harvard Review, Summer 1963, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 20-22

18. One River, Wade Davis, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996, p. 155

19. “The Colonization of the Ayahuasca Experience,” Mark Hay, November 4, 2020

https://daily.jstor.org/the-colonization-of-the-ayahuasca-experience/

See also:

Economic Botany Vol. 26, No. 2, Apr. – Jun., 1972 “Ayahuasca,” the South American Hallucin… This is the metadata section. Skip to content viewer section. JOURNAL ARTICLE “Ayahuasca,” the South American Hallucinogenic Drink: An Ethnobotanical and Chemical Investigation Laurent Rivier, Jan-Erik Lindgren Economic Botany, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Apr. – Jun., 1972), pp. 101-129 (29 pages) https://www.jstor.org/stable/4253328 Contribution from Springer https://www.jstor.org/stable/4253328?mag=the-colonization-of-the-ayahuasca-experience&seq=29

“First, Brazilian ayahuasca religions, or syncretistic churches such as the Santo Daime and União do Vegetal (UDV), developed spiritual doctrines around the brew as a sacrament in the early- to mid-twentieth century (Labate and Araújo 2004; MacRae 2004). Second are the psychonautic uses of the ayahuasca brew in comparatively non-structured contexts by consumers who may buy the dried plant material by mail order over the Internet and prepare and consume it at home (Halpern and Pope 2001; Ott 1994). Third is cross-cultural vegetalismo, or indigenous-style ayahuasca healing ceremonies conducted in an often overtly commodified way for non-indigenous clients both in the Amazon and abroad (Dobkin de Rios and Rumrill 2008; Luna 2003).”

“Ayahuasca healing beyond the Amazon: the globalization of a traditional indigenous entheogenic practice,” KENNETH W. TUPPER, Global Networks 9, 1 (2009) 117–136. ISSN 1470–2266. © 2009

ciencia.udv.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Global_Networks_2009_Tupper.pdf

20. “Alan Shoemaker, an American who visited Iquitos in the 90s, organized one of the first shaman’s tours in the U.S., trained as a curandero, and now runs a center near Iquitos, says that local police tell him “they believe that on any given Friday night 10 percent of the population is in a ceremony.” That’s out of a metro area population of about 500,000 Peruvians.”

“The Colonization of the Ayahuasca Experience,” Mark Hay, November 4, 2020

https://daily.jstor.org/the-colonization-of-the-ayahuasca-experience/

21. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ayahuasca

22. Ibid. See also: https://psytechglobal.com/ayahuasca/

23. https://mushroomdispensary.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/AYAHUASCA-users-guide.pdf

24. “Do not mix 5-MeO-DMT with prescription drugs, including SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), MAOIs (monoamine oxidase inhibitors), or other antidepressants or antipsychotics. Anyone mixing 5-MeO-DMT with harmala alkaloids should be extremely careful, as these can also cause potentially lethal consequences.”

https://tripsitter.com/5-meo-dmt/

25. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ayahuasca

26. “‘Guardians’ told Ayahuasca ceremony participants to ignore dying man, NSW inquest told – Dentist tells coroner he heard the laboured breathing of a visibly unwell man in the silence between songs,” Joe Hinchliffe, 11 May 2023

https://www.theguardian.com/ichmond-news/2023/may/11/guardians-told-ayahuasca-ceremony-participants-to-ignore-dying-man-nsw-inquest-told

27. “In October 2021, Australian man Jarred Antonovich died at a festival in New South Wales from a perforated oesophagus suspected to be caused by excessive vomiting after being administered kambo and n,n-dimethyltriptamine. After a car accident in 1997 from which he had to learn to walk and talk again, he was left with lasting impediments, the inquest heard, which may have contributed to the esophageal rupture. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kambo_(drug)

28. Ambulance officers not told about dying man’s use of powerful psychedelic and Kambo frog poison ABC North Coast / By Bruce MacKenzie Posted Mon 8 May 2023

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-05-08/inquest-jarred-antonovich-death-ayahuasca-kambo-frog-poison/102318674

See also:

“‘Has anyone called an ambulance?’ Kambo inquest continues,” David Lowe, May 12, 2023 https://www.echo.net.au/2023/05/has-anyone-called-an-ambulance-kambo-inquest-continues-rev/

29. ‘I was sexually abused by a shaman at an ayahuasca retreat’ Published 16 January 2020 https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-51053580

30. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legal_status_of_ayahuasca_by_country

Ayahuasca, global consumption & reported deaths in the media 16 July 2023 The International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC) https://idpc.net/publications/2023/07/ayahuasca-global-consumption-and-reported-deaths-in-the-media

Italy’s recent decision to schedule ayahuasca 14 May 2022 https://idpc.net/news/2022/05/italy-s-recent-decision-to-schedule-ayahuasca

Colombian Shaman Arrested for Ayahuasca on Arriving in US, psmith, November 02, 2010 https://stopthedrugwar.org/chronicle/2010/nov/02/colombian_shaman_arrested_ayahua

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/22/spanish-couple-arrested-over-toad-venom-and-ayahuasca-rituals

31. “According to the Ayahuasca Defense Fund, a program of ICEERS that provides legal support to those criminalized for ayahuasca and other teacher plants, another 31 people across the world (including seven in the US) are facing criminal charges for transporting or importing entheogens, with some being held in jail ahead of trial. ‘There has been an increase in arrests for importing or traveling with plant medicines, including ceremony raids in Spain and Italy [which this year placed ayahuasca in the most restrictive drug schedule],’ it said in a recent update to supporters.”

“There’s a Worldwide Spike in Arrests of Plant Medicine Practitioners – From Mexico to the Czech Republic, facilitators are currently being held for transporting ayahuasca, peyote, and other ancestral medicines,” Mattha Busby // November 21, 2022

https://doubleblindmag.com/ayahuasca-practitioner-arrests/

See also:

https://chacruna.net/breaking-news-the-first-two-ayahuasca-convictions-united-states/

https://www.tampabay.com/news/courts/criminal/Probation-ordered-for-Tampa-man-who-brought-South-American-spiritual-tea-to-airport_172307946/

32. How Our Santo Daime Church Received Religious Exemption to Use Ayahuasca in Canada, July 17, 2017 https://chacruna.net/how-ayahuasca-church-received-religious-exemption-canada/

33. “Tina ‘Kat’ Courtney CEO Plant Medicine People, Plant Medicine/Ayahuasca/Psychedelic Integration Specialist 3mo Last year I was arrested for Ayahuasca and faced 40 years in prison. This year I am the CEO of a Plant Medicine company and am in a delicious creative vortex. When we hit our lowest points, we are open to the greatest change.” https://www.linkedin.com/posts/tinacourtney_last-year-i-was-arrested-for-ayahuasca-and-activity-7064005937224712193-Yvie

See also:

https://www.plantmedicinepeople.com/blog/arrested-for-ayahuasca

34. Banisteriopsis caapi (cv) `Da Vine` – USPP5751P United States https://patents.google.com/patent/USPP5751P/en

35. “Co-Developing Drugs with Indigenous Communities: Lessons from Peruvian Law and the Ayahuasca Patent Dispute,” Daniel S. Sem, Concordia University, Wisconsin, Richmond Journal of Law & Technology, Volume 23, Issue 1, Article 1, 12-2-2016, p. 14

https://scholarship.richmond.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1432&context=jolt

36. “Ayahuasca healing beyond the Amazon: the globalization of a traditional indigenous entheogenic practice,” KENNETH W. TUPPER, Global Networks 9, 1 (2009) 117–136. ISSN 1470–2266. © 2009

ciencia.udv.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Global_Networks_2009_Tupper.pdf

See also:

https://jolt.richmond.edu/files/2016/12/Sem-Final-Edit-Author-Approval-1.pdf

https://www.ciel.org/project-update/protecting-traditional-knowledge-ayahuasca/

https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ReexaminationofUSPlantPatent5751.pdf

37. United States Patent #Plant 5,751, Miller, Jun. 17, 1986

https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/a7/b6/d4/2db4c56b110116/USPP5751.pdf

38. “The small flowers are pink or rose-colored.”

“B. caapi,” Plants of the Gods, Richard Evans Schultes & Albert Hofmann, Healing Arts Press, Rochester, Vermont, 1992, p. 35 (First published by McGraw-Hill, 1979)

“3. Plants of Florida: Banisteriopsis caapi, Field Museum of Natural History Herbarium Accession Sheet No. 1910734 (mounted March 28, 1983) [Exhibit No. 3]. This sheet shows a specimen of B. caapi collected by Dr. Timothy Plowman (Plowman coll. no. 12972). It contains his notes describing the specimen as having flower buds ‘deep rose pink. Petals rose pink, the limb fading to creamy white with age, the claw remaining pale pink.’ The specimen was taken from an individual that was planted in South Miami, Florida, which had been grown from a cutting collected in Ecuador in August 1979.

- Plants of Florida: Banisteriopsis caapi, Field Museum of Natural History Herbarium Accession Sheet No. 1910747 (mounted March 28, 1983) [Exhibit No. 4]. This sheet shows a specimen of B. caapi collected by Dr. Timothy Plowman (Plowman coll. no. 12973). It contains his notes describing the specimen as having flower petals that are ‘rose pink, fading completely white with age.’ The specimen was taken from an individual planted in South Miami, Florida that had been grown from a cutting collected in Peru in August 1967.”

IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE In re Request for Reexamination of U.S. Patent No. Plant 5,751 (Patentee: Loren S. Miller) Issued: June 17, 1986 Primary Examiner: James R. Feyrer Filed: Nov. 7, 1984 For: BANISTERIOPSIS CAAPI (cv) “DA VINE,” p. 6

https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ReexaminationofUSPlantPatent5751.pdf

See also:

https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/PTODecisionAnalysis.pdf

39. Drug Policy and Indigenous Peoples, Julian Burger and Mary Kapron, Health and Human Rights Journal, 2017 Jun; 19(1): 269–278.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5473056/

40. Ayahuasca Tourism is Ripping Off Indigenous Amazonians, Ann Babe, May 10, 2016

https://www.vice.com/en/article/qbn8vq/ayahuasca-tourism-is-ripping-off-indigenous-amazonians

41. “Crappy Ayahuasca Can Kill You – A British teenager died after drinking yage in South America last week.” Michael Allen, April 29, 2014

https://www.vice.com/en/article/exmpww/a-beginners-guide-to-ayahuasca

42. ‘Spiritual extractivism”: Ayahuasca, colonialism, and the death of a healer, 16th July 2019

https://ecologise.in/2019/07/16/spiritual-extractivism-ayahuasca-colonialism-and-the-death-of-a-healer/

43. “Ayahuasca healing beyond the Amazon: the globalization of a traditional indigenous entheogenic practice,” KENNETH W. TUPPER, Global Networks 9, 1 (2009) 117–136. ISSN 1470–2266. © 2009

http://ciencia.udv.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Global_Networks_2009_Tupper.pdf