Traditional Medicine Part 2: UNDRIP and Biopiracy

CANNABIS CULTURE – Can psychoactivists – both Indigenous and settler – team up to legalize all drugs, while at the same time fight the bio-pirates and avoid the same corporate cartelization of the emerging psychoactive/psychedelic medicine economy that the pot economy currently suffers from?

Part 2 of a series of deep dive articles about traditional medicine.

Part 1 can be found here.

“Currently, intellectual property rights protect ideas that can be demonstrated as being novel and undiscovered at the time of its legal claim as intellectual property.”

- “Plants As Intellectual Property,” “Plant Breeders Rights,” Wikipedia (1)

“. . . as the world’s leading authority on hallucinogenic plants, he sparked the psychedelic era with his discoveries.”

- Wade Davis, discussing Richard Evans Schultes in the preface to his 1996 book One River. (2)

“ . . . Richard Evans Schultes, discoverer of dozens of plants used by Indigenous healers . . .”

- James Fadiman, Ph. D., The Psychedelic Explorers Guide, 2011 (3)

Caño Guacayá, Río Miritiparaná, April 1952. Schultes being administered a dose of Amazonian tobacco. Photo from The Lost Amazon by Wade Davis, 2004, p. 20

“He’s often credited as the ‘discoverer of magic mushrooms,’ but Schultes himself was always quick to point out that ethnobotanists don’t ‘discover’ anything – it’s shown to us or taught to us by our Indigenous guides and our Indigenous teachers.”

- Mark J. Plotkin, Ph.d., Harvard University ethnobotanist, discussing Richard Evans Schultes, the person who introduced peyote, magic mushrooms and ayahuasca to the settlers, in 2022. (4)

“But we have been marginalized and kept out. Rick, I have asked you many times in training, ‘where are the Indigenous people of these lands, the elders? I put together a panel that you guys did not respond to and I had to fight the community – had to fight to get people here. You weren’t there. We had Navajo elders. So Rick, where are you with us?”

– Protester Dr. Angela Beers, raising the issue of the lack of sufficient support for Indigenous healers from MAPS founder and former executive director Rick Doblin at the closing ceremony of the #PS23 Psychedelic Science Conference in Denver, Colorado, June 23rd, 2023. (5)

“So hard to be in front of here. This is very challenging. I want you to be aware that you have been deceived by this movement. . . . The plant medicine’s Renaissance within the Western system and has been happening for decades through the Indigenous people. We open our medicines for you to heal – not to take, not to extract. So this movement is not a renaissance. It’s been happening already for a long time. . . . Bringing the medicines for you to heal – you’re taking it, you’re colonizing it. You’re damaging us. You’re killing or erasing our cultures. Please stop. Think. Think critically. This is not okay. You’ve been deceived and you’re going to continue being deceived. The same happened to tobacco – now causes cancer. The same happened to opioid – now causes addiction. The same happened to coca – now cocaine causes a lot of harm. Please look at the cycle of colonization and how this continues to happen.”

– Protester Kathoomi Castro, addressing conference attendees at the closing ceremony of the #PS23 Psychedelic Science Conference in Denver, Colorado, June 23rd, 2023. (6)

Image #2: Protester Kathoomi Castro, addressing the #PS23 conference attendees.

https://www.tiktok.com/@orozcoitl/video/7248478659231632682

Psychedelic Protest

The last two quotes from above came from two protesters who insisted on speaking – in spite of not being invited to speak – at the closing ceremonies of #PS23 – the “largest psychedelics conference in the world,” which happened in late June of 2023 in Denver. These quotes were spread on Twitter – and a couple other websites mentioned the protest – (7) but Lucid News was the only website to name the protesters, or go into any detail about it, which they did in their “final roundup” summary of the conference, on June 25th. (8)

Here’s how Lucid News responded to the protest itself, a month later, on July 21st:

“In the Colorado Convention Center’s 5,000-seat Bellco Theater, at the closing of the largest psychedelics conference in the world three weeks ago, we witnessed what appeared at first to be a clash of two movements-within-the-movement. One is personified by MAPS founder and president Rick Doblin, elder and optimist, who had earlier strode onto the stage looking conspicuously like Neil Armstrong in an all white suit, as he confidently planted the flag of the arrival of the ‘Psychedelic ‘20s.’ The other movement is personified by a group of five ostensibly Indigenous-allied protestors who brought the closing ceremony’s celebratory remarks to a halt when they commandeered Doblin’s microphone and each in turn warned their fellow participants that this march of psychedelic progress is heading in an all-too-familiar direction – one that values consumption without understanding the consequences to Indigenous and other marginalized communities.” (9)

The Cycle Of Colonization

Taking Kathoomi Castro’s advice to “look at the cycle of colonization” with tobacco, with the opium poppy and with coca, one can definitely see a pattern within that cycle.

Image #3: https://www.sinchisinchi.com/the-sacred-tobacco/ancestral-history-of-tobacco/

Tobacco – used by Indigenous people – was originally much stronger, (10) and was either used along with rituals that involved fasting (11) – which made the effects more pronounced (12) – and/or mixing it with other herbs in smoking mixtures (kinnikinnick) (13) – mixtures which sometimes contained expectorants such as mullein or coltsfoot that would help remove the particulates from the lungs. (14)

Image #4: “The image shows a Mexica/Aztec farmer grinding tobacco (Florentine Codex, Book XI)” https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/health/aztec-advances-10-medicinal-use-of-tobacco

Indigenous traditional modes of tobacco administration were associated with sedation conducive to important ceremonies (15) or even hallucinogenic effects. (16)

Image #5: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/rolfe-john-d-1622/

Image #6: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/tobacco-in-colonial-virginia/

Image #7: “Tobacco Plantation, detail of a print by Richard H. Laurie, 1821 CE.” https://www.worldhistory.org/image/13409/tobacco-plantation/

When the colonists “discovered” tobacco, they selected the less-hallucinogenic, more work-friendly cultivar, (17) a selection process that has continued into the modern period, under the guise of reducing the nicotine levels in corporate cigarettes to “non-addictive levels” (18) – whatever that’s supposed to mean.

Image #8: https://pot-facts.ca/chemical-fertilizers-are-radioactive-and-the-real-cause-of-tobacco-related-cancer/

Image #9: https://abcnews.go.com/Health/tobacco-companies-hid-evidence-radiation-cigarettes-decades/story?id=14635963

Modern-day (but seldom-quoted) research has revealed the carcinogenic aspects of cigarettes to be unrelated to the nicotine, smoke, tar or even the tobacco itself – and instead a function of the (much cheaper than organic) radioactive chemical fertilizers the tobacco has been grown in for the last 120 years or so. (19) Unfortunately, for one reason or another (perhaps because of the power and influence of big chemical companies over academia) most academics are reluctant to look at this evidence, and as a result of this cowardly willful ignorance, smoked medicine such as cannabis suffers from a guilt-by-association with tobacco and is subsequently over-regulated.

Image #10: https://pot-facts.ca/there-are-currently-no-legal-limits-to-heavy-metal-content-in-either-cannabis-or-tobacco-in-canada/

Image #10: https://pot-facts.ca/there-are-currently-no-legal-limits-to-heavy-metal-content-in-either-cannabis-or-tobacco-in-canada/

The resulting tobacco regulations are also a pathetic joke: smoke – not radioactive fertilizers – is seen as the culprit, and radioactive heavy metal content is a non-issue in tobacco agriculture, cannabis agriculture and agriculture in general, as far as the mis-named “Health” Canada is concerned. (20)

Image #11: “Opiologia. Or, a treatise concerning the nature, properties, true preparation and safe use and administration of opium.” Sala, Angelus, 1618 https://wellcomecollection.org/works/mhngcew3

Image #11: “Opiologia. Or, a treatise concerning the nature, properties, true preparation and safe use and administration of opium.” Sala, Angelus, 1618 https://wellcomecollection.org/works/mhngcew3

With both opium poppies and coca leaves, the pattern was somewhat different than tobacco but similar to each other. The requirements of modern 19th century medicine resulted in more concentrated alkaloids derived from the whole plant (morphine/heroin and cocaine). Then the requirements of early 20th century white supremacy created a de-facto white monopoly on importation and distribution of these drugs – one had to be a pharmacist to distribute them legally, (21) and most (if not all) non-whites were prevented from becoming pharmacists until much later in the century. (22)

Image #12: https://www.walgreensbootsalliance.com/news-media/our-stories/shot-vaccine-history

Image #13: “Customers wait to fill prescriptions at Bayless Drug Store on Atlantic Avenue in Atlantic City in this photo from the 1950s. Alburtus Steward is the pharmacist.” Courtesy of Jim Paxson https://www.nj.com/news/j66j-2020/04/7f835c7f485282/vintage-photos-of-drug-stores-and-pharmacies-in-nj.html

When looking at the history of all psychoactive and psychedelic drugs in the world, both corporate power and white supremacy appear again and again. Sadly, even progressive groups like MAPS (the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies) – the group who organized the #PS23 conference (23) – suffer from the influence of these forces.

The website “Psymposia” collected all the “conflict of interest” statements from each of the speakers at the conference, which painted a picture of just how involved the corporations were in the world of psychedelic academia. (24) Normally at such conferences, “conflict of interest” statements would be posted prominently by each speaker at the beginning of a conference for all to see, but at #PS23, you needed a special app to see them.

Image #14: https://www.psymposia.com/magazine/maps-psychedelic-science-2023-conflict-of- interest-disclosure/

Image #14: https://www.psymposia.com/magazine/maps-psychedelic-science-2023-conflict-of- interest-disclosure/

It seems, on the surface, that Rick Doblin/MAPS wanted it to appear that MAPS supported Indigenous healers (through a token “sprinkling” of them in the conference) but didn’t want to actually support them by financing their journey to and from the conference or allow them to participate in the closing ceremonies, whereas he wanted to get material assistance from the corporate psychedelic sector and rely heavily on their academics without making it easy for participants to understand the extent of that assistance.

Pretty greasy if you ask me.

The Ground Future Articles In This Series Will Cover

In previous articles (25) – including last year’s first installment of “Traditional Medicine” (26) – I pointed out how white supremacy and Indigenous genocide was perpetuated in many ways, not least of which being the current practice of wealthy (mostly) white people getting licenses to produce and sell cannabis and then spending some of their profits lobbying the government to raid their Indigenous cannabis retailer competition out of existence. I also pointed out the history of Indigenous cannabis use and how this history might be used to assert the right to grow and sell and use cannabis for Indigenous people under the United Nations “UNDRIP” (The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples) treaty recently signed by Canada.

Image #15: https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2022/06/09/traditional-medicine/

Arguably, the rest of the stigmatized, under-utilized, over-regulated and/or sometimes prohibited psychoactive/psychedelic plant medicines (and their Indigenous-facilitated economies) also qualify for similar protection under UNDRIP.

With part 2 of this series, I wish to look more closely at what the terms “Indigenous” and “traditional medicine” means within the context of the UNDRIP treaty. I also wish to explore the meaning of the term “biopiracy.”

With future instalments of my “Traditional Medicine” series, I wish to review many of the other major psychoactive/psychedelic medicines/economies aside from cannabis that could qualify for UNDRIP protection, paying attention to their evidence of historical/traditional use, current medicinal applications, safety profiles, and legal status, along with any evidence of colonial bio-prospecting/bio-piracy that may have already transpired and/or is currently in progress with each of the plants or brews in question.

The Point I Am Attempting To Make

To be clear, I am not arguing that psychedelics or psychoactive plant medicines should be exclusively produced and sold by Indigenous people. Elsewhere I have made arguments that all harmless people ought not to be harmed, and that one can grow, sell and use cannabis, (27) coca, (28) magic mushroom (29) and other plant medicines (30) properly without harming people.

Image #16: https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2021/08/31/the-amazing-world-of-the-coca-leaf/

What I am arguing is that the rich, mostly white corporate overlords should not be allowed any more plant medicine monopolies, like they’ve recently carved out with cannabis. I am arguing that Indigenous people should be included in any and every herbal medicine economy, that Indigenous drug-related rituals should be held in high esteem, that psychoactivists should do their best to provide the resources to make it easy for Indigenous people to participate in drug peace activities and feature Indigenous elders in the opening and closing ceremonies (and in prominent panels) in all future psychedelic conferences and major drug peace events.

Image #17: https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2022/05/04/legalize-shrooms/

I am also arguing that Indigenous teachings should figure prominently in all forms of entheogenic-related educational campaigns by government and/or industry, in order that Indigenous wisdom and insight regarding the proper cultivation, proper wildcrafting, proper distribution and proper use of these plant medicines can be better understood and appreciated and so that Indigenous communities will be sustained and adequately compensated for keeping these traditions and insights alive during centuries of genocide – genocide that has yet to end.

Image #18: https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2103683118

Image #19: https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2103683118

I’m not arguing that Indigenous people should be included in medicine monopolies. Rather, I’m arguing that support for Indigenous medicine rights might be the best way to end medicine monopolies.

And maybe the quickest path to ending the ongoing genocide of Indigenous people involves all of society appreciating (culturally and financially) what Indigenous communities bring to the understanding of plant medicines. Maybe this path is also the quickest path to total global drug peace and global human medical autonomy.

Image #20: https://www.pageaday.com/products/native-american-ethnobotany/hardback

Regardless, I feel it is the responsibility of settler psychoactivists to take the lead in fighting to help realize and manifest significant cultural appreciation and financial compensation to Indigenous people for what they bring to the plant medicine world.

But more than just deal with the compensation issue, us settlers need to deal with the other problems we’ve created. The biggest problems of modern medicine are a) a bias towards proprietary medicine and against non-proprietary medicine, b) drug prohibition, c) drug producer/retailer cartels, and d) biopiracy. Settlers created these problems. Settlers should all get busy working on (or in a few cases continue to work on) solutions to end these problems.

Who Qualifies As “Indigenous”?

There are other treaties and laws – both national and international – that attempt to protect the financial and cultural rights of Indigenous peoples to their medicines (31) but the wording of UNDRIP allows a very comprehensive type of protection to be put in place, and has been adopted by most nations of the world, (32) so it’s a good treaty to focus on for psychoactivists who wish to team up on international efforts to invoke UNDRIP as an accepted and effective legal defense for Indigenous-owned psychedelic and psychoactive drug markets.

Image #21: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-are-indigenous-populations-5083698

Image #22: https://www.cigionline.org/articles/revitalizing-canadas-indigenous-constitution/

The UNDRIP definition of Indigenous is “descendants of the original people or occupants of lands before these lands were taken over or conquered by others.” (33) UN Indigenous experts estimate there are more than 370 million people who qualify as Indigenous under UNDRIP. (34)

What Qualifies As “Traditional Medicine”?

Traditional medicine isn’t specifically defined in the UNDRIP treaty, but is mentioned twice:

“Article 24

- Indigenous peoples have the right to their traditional medicines and to maintain their health practices, including the conservation of their vital medicinal plants, animals and minerals. Indigenous individuals also have the right to access, without any discrimination, to all social and health services. 2. Indigenous individuals have an equal right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. States shall take the necessary steps with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of this right.”

“Article 31

- Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions. 2. In conjunction with indigenous peoples, States shall take effective measures to recognize and protect the exercise of these rights.” (35)

Image #23: https://teentalk.ca/2017/09/19/undrip-walk-the-talk-of-reconciliation/

In part 1, I provided a strict definition of “traditional medicine” – that any medicinal practice for which there was pre-colonial evidence for would qualify. But the World Health Organization defines “Traditional Medicine” this way:

“Traditional medicine has a long history. It is the sum total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness.” (36)

Image #24: https://www.thestar.com/news/world/americas/mexico-to-use-traditional-medicine-more-cuban-doctors/article_7f099ade-abaf-5330-95f9-e67c62bcd9b3.html

Notice the lack of time frame in this definition? The WHO definition definitely includes post-colonial medicinal traditions. It could very well include post-millennial medicinal traditions – even a tradition that began yesterday.

If one goes by the Webster’s dictionary definition of tradition, it can mean a “customary pattern.” (37) Customary can mean “commonly practiced.” (38) And commonly can mean “occurring frequently.” (39)

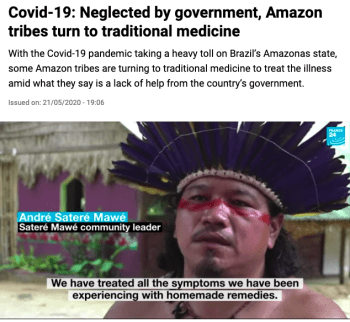

Image #25: https://www.france24.com/en/20200521-covid-19-neglected-by-government-amazon-tribes-turn-to-traditional-medicine

Image #26: https://www.france24.com/en/20200521-covid-19-neglected-by-government-amazon-tribes-turn-to-traditional-medicine

Again – no time frame attached to the word “tradition.” Tradition has to do with how wide spread the activity has been adopted rather than how long the activity has been adopted. Therefore – according to both the WHO and Websters – an inclusive definition of “traditional medicine” could very well mean “a medicinal practice that happens a lot” – with no time frame. 20% of Indigenous pot dispensaries could begin selling coca on Wednesday, and it could then qualify as a “traditional medicine” on Thursday.

This author feels that those who are interested in ending the genocide of Indigenous people should adopt the most inclusive and flexible definition of “traditional medicine” – and those people who refuse to do so should be publicly challenged to defend their position.

What is “BioPiracy”?

“Our fathers planted gardens long ago

Whose fruits we reap with joy today,

Their labor constitutes a debt we owe

Which to our heirs we must repay,

For all crops sown in any land

Are destined for a future man”

- 12th Century Arab Poet Nizami Ganjavi (40)

Image #27: https://twitter.com/RafiGurbanov/status/1346410748675829760/photo/1

From time immemorial, crops were cultivated by communities for communities, gifted to the future as a form of heritage, without any concept of a particular species of crop being the private property of one individual. Genetics were not property, they were collectively owned by all.

Same thing with knowledge. Indigenous people had an explicitly-stated ethic of sharing ideas. According to The Sacred Tree – a 1995 book about Indigenous wisdom

“Once you give an idea to a council or a meeting it no longer belongs to you. It belongs to the people.” (41)

Image #28: https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/7-incredible-traditions-of-the-native-american-872e9df21e5b

And then some people in England in the 17th century invented “intellectual property” (42) and all hell broke loose.

Image #29: https://www.americanacademy.de/event/the-origins-of-intellectual-property-in-german-renaissance-art/

The stark differences that now exist between Indigenous and settler approaches to “intellectual property” in general and medical practices in particular has been noted by researchers of plant patents:

“There are potential problems for intellectual property (IP) protection, since medical treatments in traditional cultures are typically developed by groups over long periods of time, as opposed to the more rapid discovery by individual researchers or companies in the pharmaceutical industry.” (43)

Image #30: https://www.abebooks.com/9788181581600/Biopiracy-Shiva-Dr-Vandana-8181581601/plp

One of these “problems” – the unfair transformation of a “legacy” or “heritage” cultivar of universally-held community property into the private property of an individual or corporation – is sometimes called “BioPiracy.” Simply put, BioPiracy is a deluded attempt to apply intellectual property rights to species or subspecies of living things. Unlike most Indigenous people, Europeans have this habit of considering anything and everything as property. Even ideas. Even the right to access natural stuff people just found lying around that they didn’t have anything to do with making.

Image #31: https://garystockbridge617.getarchive.net/amp/media/farmers-listening-to-sales-talk-of-patent-medicine-vendor-in-warehouse-during-95fa83

Early on in the history of patent law, abuses were common, so certain standards were set in response:

“This power was used to raise money for the Crown, and was widely abused, as the Crown granted patents in respect of all sorts of common goods (salt, for example). Consequently, the Court began to limit the circumstances in which they could be granted. After public outcry, James I of England was forced to revoke all existing monopolies and declare that they were only to be used for ‘projects of new invention’.” (44)

Image #32: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/aep/Ja1/21/3/data.pdf?view=extent

Unfortunately, the standard of “no discoveries – just inventions” was largely abandoned by 1930, when the adoption of the Plant Patent Act provided the most flexible definition of “invention” ever rationalized by greedy minds:

“During the congressional debates about the Plant Patent Act, some of the key issues were: what kinds of plant qualified as patentable subject matter; what exactly did a breeder have to do in order to qualify as an inventor; and what was the relationship between the act of invention and the act of reproducing the invention. These issues were overcome by adopting a new concept of invention that has been characterized as ‘inductive’ invention, by arguing that ‘although the ‘sports’ or spontaneous mutations from which they bred new varieties often occurred naturally, the skill of identifying the mutation, isolating it, and then reproducing it was a work of invention.’” (45)

Image #33: https://www.slideserve.com/makala/intellectual-property-protection-for-plants-in-the-united-states

As of 2020, about a dozen cannabis cultivars have been patented under US Plant Patent law, and dozens more under international “Plant Breeders’ Rights” laws. (46)

In his book Global Biopiracy – Patents, Plants, and Indigenous Knowledge, professor Ikechi Mgbeoji defines “biopiracy” as

“. . . the unauthorized commercial use of biological resources and/or associated traditional knowledge, or the patenting of spurious inventions based on such knowledge, without compensation. Biopiracy also refers to the asymmetrical and unrequited movement of plants and TKUP (Traditional Knowledge of the Use of Plants) from the South to the North through the processes of international institutions and the patent system.” (47)

Image #34: https://terraliege.com/biopiracy-the-unethical-quest-to-own-bioresources/

The pirate’s booty (these biological resources in question) up for pillaging initially excluded tubers (48) but now includes tubers such as potatoes. (49) However, the wealth resulting from plant patents is not small potatoes.

Back in 2006 it was reported that up to 4 billion people use herbs “as a primary healthcare source.” (50) Estimates of the worth of medicines derived from plants range somewhere in the tens of billions of dollars or more:

“Indigenous people also regularly suffer from the contravention of Article 31: the right to their Intellectual Property (IP). In 1985, the World Intellectual Property Organisation estimated that the annual world market for medicines derived from medicinal plants discovered from indigenous peoples amounted to US$43 billion – a figure which is certainly higher today.” (51)

Image #35: https://greensourcedfw.org/articles/indigenous-knowledge-biopiracy-modern-pillaging

Just the psychedelic medicine industry (not counting non-psychedelic psychoactive medicines such as coca, tobacco etc.) is estimated to be many billions of dollars. (52) The tobacco market by itself is estimated to be worth close to a trillion dollars. (53)

Arguably, the cannabis, coca and poppy markets could one day grow to equal or even surpass the tobacco market, given the utility of these plant medicines relative to tobacco. Magic mushrooms, kratom, damiana and yohimbe could also easily grow to be massive markets given their current appeal levels and/or applicability to modern ubiquitous medical conditions.

Image #36: https://beehivecollective.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/OGC_BioJustice.jpg

Plant medicines are easily some of the most lucrative markets on planet earth.

Major Psychoactive and Psychedelic Plant Medicines

The lists of psychoactive (54) and psychedelic plants (55) are long ones. But some plants stand out as excellent examples of effective medicines with long histories of beneficial use and/or potentially broad appeal potential to the general public.

Image #37: https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Encyclopedia-of-Psychoactive-Plants/Christian-Ratsch/9780892819782

In the opinion of this author, the major psychoactive and psychedelic plant medicines – excluding cannabis (dealt with in part 1) coffee, tea, chocolate and sugar – listed in alphabetical order, are: ayahuasca, blue & red lotus, coca, damiana, DMT-containing plants, iboga, kava, khat, kratom, LSD-esque plants, magic mushrooms, opium poppy, peyote & San Pedro, salvia, sassafras, tobacco, wormwood, and yohimbe.

Image #38: https://erowid.org/library/books_online/golden_guide/g01-10.shtml#contents

Image #39: https://www.npr.org/local/305/2020/02/06/803369014/magic-mushrooms-and-psychedelic-plants-could-be-on-the-d-c-ballot-this-november

Readers of Cannabis Culture can look forward to articles about all these plants in relation to the traditional medicine rights found in the UNDRIP treaty in the near future, beginning with ayahuasca.

Citations:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plant_breeders%27_rights

- Wade Davis, One River, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1996, p. 2

- James Fadiman, Ph. D., The Psychedelic Explorers Guide, Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont, 2011, p. 228

- “The Life of a Harvard Ethnobotanist,” Harvard Magazine, Jun 15, 2022 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1ufH6lUTAE&t=7s

- POC Psychedelic Collective, Twitter video post from June 28th, 2023 https://twitter.com/POCpsychedelics A more complete version can be found here: https://www.tiktok.com/@orozcoitl/video/7248449685822655787

- orozcoitl, TikTok video post from June 24th, 2023 https://www.tiktok.com/@orozcoitl/video/7248478659231632682A collection of videos of this protest can be seen here: https://www.tiktok.com/@orozcoitl

- https://www.salon.com/2023/06/25/science-and-corporadelics-in-colorado-can-mushroom-capitalism-save-us-from-an-existential-crisis/ https://medium.com/@emilylorin/mad-pride-from-a-burnt-out-therapist-5b913044c3c1

- https://www.lucid.news/report-final-round-up-from-mapss-psychedelic-science-2023/

- “‘What Just Happened?’ Processing the Closing Protest at Psychedelic Science,” ARIEL CLARK , ROMAN HAFERD, JULY 21, 2023 https://www.lucid.news/processing-closing-protest-at-psychedelic-science/

- “Nicotiana rustica, commonly known as Aztec tobacco or strong tobacco, is a rainforest plant in the family Solanaceae. It is a very potent variety of tobacco, containing up to nine times more nicotine than common species of Nicotiana such as Nicotiana tabacum (common tobacco). More specifically, N. rustica leaves have a nicotine content as high as 9%, whereas N. tabacum leaves contain about 1 to 3%. The high concentration of nicotine in its leaves makes it useful for producing pesticides, and it has a wide variety of uses specific to cultures around the world. However, N. rustica is no longer cultivated in its native North America, (except in small quantities by certain Native American tribes) as N. tabacum has replaced it.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicotiana_rustica

- “Cane Tobacco well dryed, and taken in a silver pipe, fasting in the morning, cureth the megrim, the tooth ache, obstructions proceeding of cold, and helpeth the fits of the mother.” https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A14295.0001.001/1:7.8.1?rgn=div3;view=fulltext Vaughan W. Directions for Health, both Naturall and Artificial: derived from the best physitians as well moderne as auncient. London: T Snodham for R Jackson, 1612 https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A14295.0001.001?view=toc “The old man was more puzzled than ever, so he decided to fast and see if the Great Spirit would tell him what he wanted to know. When he had gone without food for two days, the Great Spirit appeared to him and told him to gather the leaves and dry them to pray with, to burn in the fire as incense, and to smoke in his pipe. He was told that tobacco should be the main offering at every feast and sacrifice.” “Ceremonial Use of Tobacco” https://www.mpm.edu/content/wirp/ICW-166 “In former times, initiates among the Ayoreo Indians of the Paraguayan Chaco had to drink a cold-water extract (maceration) of tobacco leaves as part of the process of becoming a shaman (maijna). Each novice was required to fast for two days before receiving the drink.” Christian Ratsch, The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants, Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont, 2005, p. 385

- “There is considerable variability in the rates and extent of drug metabolism between patients due to physiological, genetic, pharmacologic, environmental and nutritional factors such as fasting. This variability in drug metabolism may result in treatment failure or, conversely, in increased side effects or toxicity.” Laureen A. Lammers, Roos Achterbergh, Ron A.A. Mathôt & Johannes A. Romijn (2020) The effects of fasting on drug metabolism, Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, 16:1, 79-85, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17425255.2020.1706728 See also: https://erowid.org/experiences/subs/exp_Fasting.shtml Mr. Yukk. “Fasting Can Be Fun: An Experience with Caffeine & Tobacco – Cigarettes (exp49451)”. Erowid.org. Dec 25, 2006. https://erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=49451

- “Cutler cites Edward S. Rutsch’s study of the Iroquois, listing ingredients used by other Native American tribes: leaves or bark of red osier dogwood, arrowroot, red sumac, laurel, ironwood, wahoo, huckleberry, Indian tobacco, cherry bark, and mullein, among other ingredients.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinnikinnick

- “Leaves were smoked to attempt to treat lung ailments, a tradition that in America was rapidly transmitted to Native American peoples.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verbascum_thapsus “Coltsfoot is commonly smoked in combination with other medicines to cure coughs and chest issues. Coltsfoot flowers, leaves, and even budding can be used to smoke.” https://meomarleys.com/blogs/smokable-herbs-tobacco-alternatives/can-i-smoke-coltsfoot

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceremonial_pipe

- “Nicotiana rustica is called mapacho in South America. It is often used for entheogenic purposes by South American shamans, because of its high nicotine content and comparatively high levels of beta-carbolines, including the harmala alkaloids harmane and norharmane. There are many methods of administration in South American ethnobotanical preparations. In a preparation known as singado or singa, N. rustica is allowed to soak or be infused in water, and the water is then insufflated into the stomach. In Peru its known as ‘Mapacho’ and smoked in pipes, the juice is also drunk for its hallucinogenic effects.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicotiana_rustica

- “In 1612, John Rolfe arrived in Jamestown to find the colonists there struggling and starving. He had brought with him a new species of tobacco known as nicotiana tabacum. This species was preferable to the native nicotiana rustica as it was much smoother.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tobacco_in_the_American_colonies “Nicotiana rustica, commonly known as Aztec tobacco or strong tobacco, is a rainforest plant in the family Solanaceae. It is a very potent variety of tobacco, containing up to nine times more nicotine than common species of Nicotiana such as Nicotiana tabacum (common tobacco). More specifically, N. rustica leaves have a nicotine content as high as 9%, whereas N. tabacum leaves contain about 1 to 3%. The high concentration of nicotine in its leaves makes it useful for producing pesticides, and it has a wide variety of uses specific to cultures around the world. However, N. rustica is no longer cultivated in its native North America, (except in small quantities by certain Native American tribes) as N. tabacum has replaced it.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicotiana_rustica

- “Nicotine per se is not recognized as a carcinogen, but the World Health Organization (2015) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (2018) have recommended a mandated lowering of nicotine levels in combustible cigarettes to non-addictive levels in order to reduce overall addiction to such products and to lower corresponding toxicant exposure. The specific concentrations at which nicotine becomes non-addictive in combustible cigarettes may be difficult to determine and may vary amongst individuals, but Benowitz and Henningfield (1994) have predicted tobacco filler nicotine contents of between 0.02 and 0.03% to be below a ‘sub-threshold level of addiction.’ The World Health Organization (2015) has recommended lowering of nicotine content of the tobacco filler to below 0.04%. Percent nicotine on a dry weight basis in conventional tobacco cultivars typically ranges from between 1.0 and 5.0%, with observed variability being due to market type (burley, flue-cured, dark, cigar, or Oriental), plant genetics, growing environment, and stalk position. Manufacturers blend sourced cured leaf to produce cigarette tobacco filler with between 1.0 and 2.0% nicotine on a dry weight basis.” “Genetic and Agronomic Analysis of Tobacco Genotypes Exhibiting Reduced Nicotine Accumulation Due to Induced Mutations in Berberine Bridge Like (BBL) Genes,” Ramsey S. Lewis, Katherine E. Drake-Stowe, Crystal Heim, Tyler Steede, William Smith, Ralph E. Dewey, Front. Plant Sci., 03 April 2020 Sec. Plant Biotechnology Volume 11 – 2020 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2020.00368/full

- https://pot-facts.ca/big-tobacco-knew-radioactive-particles-in-cigarettes-posed-cancer-risk-but-kept-quiet/ https://pot-facts.ca/chemical-fertilizers-are-radioactive-and-the-real-cause-of-tobacco-related-cancer/

- https://pot-facts.ca/there-are-currently-no-legal-limits-to-heavy-metal-content-in-either-cannabis-or-tobacco-in-canada/

- “The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) of 1906 was the first federal law to establish the FDA as the main regulatory body for all medications in the United States. This role became more complex with the Durham-Humphrey Amendment of 1951 and the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA). These acts defined the two classes of federally regulated medications: OTC and prescription medications. Ultimately, these acts established the criteria for labeling a medication as a prescription drug, with the following requirements: The use of such a drug is safe only under the supervision of a licensed practitioner due to its toxicity or method of use.” “Federal Regulation of Medication Dispensing,” Amanda E. Miller; Samar Nicolas, June 20, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK582130/ “In the House of Commons on July 10, 1908, the Minister of Labour proposed the adoption of a motion prohibiting: ‘the importation, manufacture and sale of opium for other than medicinal purposes.’ The motion was adopted without debate. The Minister introduced Bill 205, An Act to prohibit the importation, manufacture and sale of opium for other than the medicinal purpose. (Opium Act, 1908). The first section of the Act prohibited the importation of opium without authorization from the Minister of Customs. Additionally the drug could be used for medical purposes only. The manufacture, sale and possession for the purpose of selling crude opium or opium prepared for use by smokers was also prohibited. Whoever violated these provisions could be found guilty of a criminal offence punishable by a maximum prison term of three years and/or a minimum fine of $50 and not exceeding $1,000. Even though it prohibited the use of opium, the legislation was aimed at opium dealers, most of whom were Chinese, and not users. The bill was given Royal Assent on July 20, 1908.” Chapter 13 – Regulating Therapeutic Use of Cannabis Opium Act, 1908 https://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/library/studies/canadasenate/vol2/chapter12_opium_act_1908.htm

- “In 1933 the NAACP undertook Hocutt v. Wilson, the first test case involving segregation in higher education. The plaintiff was Thomas R. Hocutt, a student at the North Carolina College for Negroes, who had been denied admission to the University of North Carolina’s School of Pharmacy. Attorneys Conrad O. Pearson and Cecil McCoy appealed to the NAACP for assistance after filing a law suit. Charles Houston recommended William Hastie to direct the litigation. According to Pearson, “the white Bar [in attendance] was unanimous in its praise,” of Hastie’s and his colleagues’ trial performance, but the case was undermined by the North Carolina College President’s refusal to release Hocutt’s transcript.” https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/brown/brown-segregation.html

“In British Columbia, Chinese professionals were barred for years from practicing such professions as law, pharmacy and accountancy. The first Chinese-Canadian lawyers were called to the Bar only in the 1940s. Since then, discriminatory laws have been repealed.” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chinese-canadians

“Jarron Yee was the very first aboriginal owner and operator of a pharmacy in our great province. He opened up The Medicine Shoppe on 9th Ave North in 2010.”

“Jarron Yee,” CBC News · Saskatchewan, Mar 08, 2016

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/jarron-yee-1.3482464

23. https://maps.org/bulletin-evolution-of-psychedelic-science-conference/

https://maps.org/product/ps23-molecule-t-shirt/

24. “Every Disclosed Conflict of Interest at Psychedelic Science 2023,” Russell Hausfeld, June 21, 2023 https://www.psymposia.com/magazine/maps-psychedelic-science-2023-conflict-of-interest-disclosure/

25. “The Raid Lobby,” David Malmo-Levine, September 25, 2022 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2022/09/25/the-raid-lobby/

“Killed Over Pot,” David Malmo-Levine, May 18, 2021 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2021/05/18/killed-over-pot/

26. “Traditional Medicine,” David Malmo-Levine, June 9, 2022 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2022/06/09/traditional-medicine/

27. “Be The Change : How to Defend Yourself in Court from ‘Legalization’,” David Malmo-Levine, December 20, 2018

https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2018/12/20/be-the-change-how-to-defend-yourself-in-court-from-legalization/

28. “The Amazing World of the Coca Leaf,” David Malmo-Levine, August 31, 2021 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2021/08/31/the-amazing-world-of-the-coca-leaf/

29. “LEGALIZE SHROOMS,” David Malmo-Levine, May 4, 2022

https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2022/05/04/legalize-shrooms/

30. “COVID-19, Cannabis & Herbal Medicine,” David Malmo-Levine, March 30, 2020 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2020/03/30/covid-19-cannabis-herbal-medicine/

“COVID-19, Cannabis & Herbal Medicine Part 2: Gain-Of-Function,” David Malmo-Levine, September 24, 2020 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2020/09/24/covid-19-cannabis-herbal-medicine-part-2-gain-of-function/

“COVID-19, Cannabis & Herbal Medicine Part 3: Reasons I Refuse To Be Vaccinated,” David Malmo-Levine, September 14, 2021 https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2021/09/14/covid-19-cannabis-herbal-medicine-part-3-reasons-i-refuse-to-be-vaccinated/

31. “Traditional Indigenous medicine is currently far from being widely protected by law. As of 2022, only the constitutions of Bolivia (Art. 42), and Ecuador (Art. 57) include regulation specific to Indigenous traditional medicine. Other relevant frameworks that mention Indigenous rights to the use and development of their traditional medicines and related practices are the ILO Convention No. 169 (Art. 25.2), UNDRIP (Arts. 24 and 31), the American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Art. 13; Art. 18; Art. 28), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (Art. 8 [j], 16, and Annex 1) and its Nagoya protocol on Access and benefit-sharing (Art. 7 and Art. 12), the Sharm El-Sheikh Declaration (2018), UNESCO’s Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems Program (LINKS), and UNESCO’s policy on engaging with Indigenous Peoples. In addition, the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) issued a report on Indigenous Traditional Knowledge in 2012, recommending the inclusion of the protection of Indigenous intellectual property to the World International Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Over the years, the topic of intellectual property has been included in UNPFII sessions, with the most recent in its twenty-first session held in 2022. Yet, despite the established legal frameworks noted here, none specifically addresses Indigenous traditional medicine’s rapid commodification and commercialization in the West in certain fields of practice.”

“Ethical principles of traditional Indigenous medicine to guide western psychedelic research and practice,” Yuria Celidwen, Nicole Redvers, Cicilia Githaiga, Janeth Calambás, Karen Añaños, Miguel Evanjuanoy Chindoy, Riccardo Vitale, Juan Nelson Rojas, Delores Mondragón, Yuniur Vázquez Rosalío, Angelina Sacbajá, December 16, 2022

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(22)00227-7/fulltext

32. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Declaration_on_the_Rights_of_Indigenous_Peoples

33. “Know Your Rights – United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples for Indigenous adolescents,” Human Rights Unit, Programme Division, New York, 2013, p. 5

https://sites.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/HRBAP_UN_Rights_Indig_Peoples.pdf

34. “This is a Declaration which makes the opening phrase of the UN Charter, ‘We the Peoples…’ meaningful for the more than 370 million indigenous persons all over the world.”

Statement by Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, Former Chairperson of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, to the United Nations General Assembly, on the occasion of the adoption by the United Nations General Assembly of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on 13 September 2007 “Know Your Rights – United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples for Indigenous adolescents,” Human Rights Unit, Programme Division, New York, 2013, p. 3

https://sites.unicef.org/policyanalysis/rights/files/HRBAP_UN_Rights_Indig_Peoples.pdf

35. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 13 September 2007

https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/512/07/PDF/N0651207.pdf?OpenElement

36. “Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine” https://www.who.int/health-topics/traditional-complementary-and-integrative-medicine#tab=tab_1

37. “. . . an inherited, established, or customary pattern of thought, action, or behavior . . .” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/tradition

38. “. . . commonly practiced, used, or observed . . .” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/customary

39. “. . . occurring or appearing frequently . . .”

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/commonly

40. The Origin of Agriculture and Crop Domestication, The Harlan Symposium, May, 1997, P. 51

https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnacf852.pdf

41. The Sacred Tree, J. Bopp, M. Bopp, L. Brown, P. Lane, P. Lucas, Four Worlds Development Press, University of Lethbridge, second edition, 1995

42. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intellectual_property

43. Daniel S. Sem, Co-Developing Drugs with Indigenous Communities: Lessons from Peruvian Law and the Ayahuasca Patent Dispute, 23 Rich. J.L. & Tech. 1 (2016)

https://jolt.richmond.edu/files/2016/12/Sem-Final-Edit-Author-Approval-1.pdf

44. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_patent_law

45. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plant_Patent_Act_of_1930

46. Jocelyn Bosse (2020) ‘Before the High Court: the legal systematics of Cannabis’ Griffith Law Review, 29:2, pp. 42-45

https://deliverypdf.ssrn.com/delivery.php

47. Global Biopiracy – Patents, Plants, and Indigenous Knowledge, Ikechi Mgbeoji, UBC Press, Vancouver, B.C., 2006 p. 13

48. “The Plant Patent Act of 1930 (enacted on 1930-06-17 as Title III of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff, ch. 497, 46 Stat. 703, codified as 35 U.S.C. Ch. 15) is a United States federal law spurred by the work of Luther Burbank and the nursery industry. This piece of legislation made it possible to patent new varieties of plants, excluding sexual and tuber-propagated plants (see Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970).”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plant_Patent_Act_of_1930

49. Potato cultivar FL 2027, US20050081269A1, United States, Inventor: Robert Hoopes, Current Assignee: Frito Lay North America Inc

https://patents.google.com/patent/US20050081269A1/en

50. “It has been reported that, up to four billion people living in the developing countries rely directly on herbal medicines as a primary healthcare source (Bandaranayake, 2006).”

“Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology Acute and sub-acute toxicological evaluation of lyophilized Nymphaea x rubra Roxb. ex Andrews rhizome extract,” Kushal Kumar, Sabeena Sharma, Ashish Kumar, Pushpender Bhardwaj, Kalpana Barhwal, Sunil Kumar Hota, Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology Volume 88, August 2017, Pages 12-21 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0273230017300934

51. “How the War on Drugs Attacks Indigenous Culture,” Ryan Hesketh, April 10, 2019

https://www.talkingdrugs.org/how-the-war-on-drugs-attacks-indigenous-culture/

52. “The economic profits alone of the psychedelic industry is expected to grow to 6.85 billion by 2027.”

“Ethical principles of traditional Indigenous medicine to guide western psychedelic research and practice,” Yuria Celidwen, Nicole Redvers, Cicilia Githaiga, Janeth Calambás, Karen Añaños, Miguel Evanjuanoy Chindoy, Riccardo Vitale, Juan Nelson Rojas, Delores Mondragón, Yuniur Vázquez Rosalío, Angelina Sacbajá, December 16, 2022

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(22)00227-7/fulltext

53. “The global tobacco market size was estimated at USD 867.55 billion in 2022 and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.1% from 2023 to 2030 due to the rising tobacco consumption in the developing regions of Asia and Africa.”

“Tobacco Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product (Smokeless Tobacco, Cigarettes, Cigars & Cigarillos, NGPs, Kretek), By Distribution Channel (Supermarket/Hypermarket, Online), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2023 – 2030”

https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/tobacco-market

54. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_psychoactive_plants,_fungi,_and_animals

55. http://ssf.f15ijp.com/wiki/index.php/List_of_psychedelic_plants