George H.W. Bush: Biggest. Drug Lord. Ever. (Part 2)

CANNABIS CULTURE – Part 2: In Cuba & Dallas with Op. 40, Vietnam & Laos with the Secret Team

This is part two in an ongoing series attempting to provide in a systematic way the best evidence of CIA drug trafficking in general, and President George H.W. Bush’s key role in those activities in particular.

Part one – where we learn about Skull and Bones (the Yale fraternity started by the biggest drug smugglers of the 1800’s, who created the modern drug war which began in the early 1900’s and who also created the CIA in the mid 1940’s) – can be found here.

“Our paramilitary teams and boat operators were in and out of Cuban waters all the time and had the opportunity to meet with Cuban fishing trawlers at places like the island of Cay Sal. I did not want the teams and operators moving illicit drugs out of Cuba.”

– Ted Shackley, Spymaster: My Life In The CIA, 2005 (109)

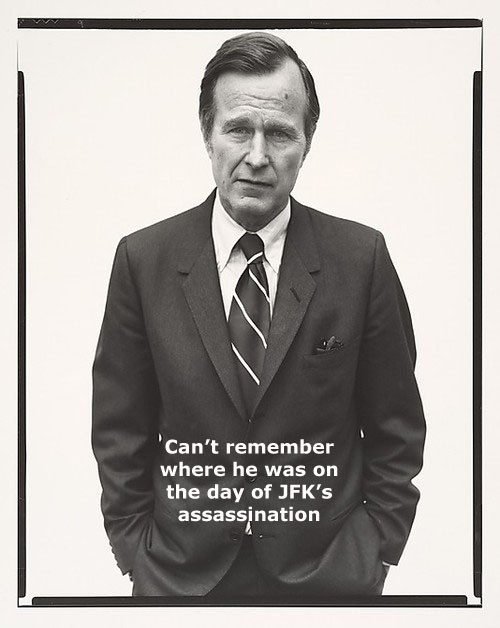

“He also claimed that he did not remember where he was the day John F. Kennedy was killed – ‘somewhere in Texas,’ he said. George Bush is possibly the only person on the planet who did not recall his whereabouts that day, although his wife clearly remembered their being in Tyler.”

– Kitty Kelley, The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty, 2004 (110)

“All I gotta do now is take Dick Cain and work deals for the CIA and the Outfit … all over the world. … Overseas is where it’s all headin’, Chuck,” Mooney continued. I’ve got Trafficante on board for Asia. The Vietnam War is gonna make a lot of guys rich.”

– Mob boss Sam Giancana, speaking in 1966, “Double Cross”, 1992 (111)

Part 2: Chapter 1: Ted Shackley aka The Blonde Ghost

We begin our story exactly where we left off, with evidence of long-time Bush associate and CIA station chief in Miami and Laos – Ted Shackley – said to have been smuggling planeloads of drugs as far back as 1959:

“Bowen then enlarged upon the purpose of that trip. He stated that this trip occurred several years before Shackley was made CIA chief in Miami, and that Shackley was instrumental in setting up the CIA drug trafficking into the United States from South America. Bowen said that the series of flights went from Miami, to Columbia, to Quayaqui, to Lima, and then to Arequita. After the plane left Arequita going eastbound over the Andes, one of the two engines failed, causing the aircraft to lose altitude. Bowen was able to maneuver the aircraft into one of the few available flat areas, and crash-landed the plane. Bowen said that Shackley had arranged for cocaine to be loaded on board the aircraft, where it was hidden in the tail section. Bowen, Shakley, and the others then abandoned the crashed aircraft. Eventually, the Bolivian authorities discovered the drugs, but the pilots and passengers were long gone.” (112)

Ted Shackley had an interesting career with the CIA. Nicknamed “the Blonde Ghost” due to his blonde hair, pale features and “mysterious ways”, he was one of the most highly decorated CIA agents ever. (113)

Between 1962 an 1965, Shackley was the station chief in Miami Florida – the biggest CIA base outside of their headquarters in Langley, Virginia. He worked there with Major General Edward Lansdale of the OSS/CIA, along with other CIA operatives in the area, no doubt including George H.W. Bush (being the “born and raised in the CIA” intelligence brat that he was) who was in the Gulf of Mexico with his off-shore oil rig business. Shackley was also well acquainted with many of the politically active or militarily inclined “Miami Cubans” who escaped from Fidel Castro’s revolution – all working hard to defeat Castro in any way possible.

It is surely no coincidence that both of the largest CIA stations of the 1960’s – Miami, Florida and Vientiane, Laos – were at the end and the beginning of the “French Connection” drug trafficking route. Often the route was from the Golden Triangle to Marseille, France to Havana, Cuba to Miami, Florida – at least until Castro took over Cuba. (114)

Also it was no coincidence that Ted Shackley was in charge of both stations. He needed to keep a close watch on agency drug operations, as it was the thing they did that would eventually pay for most of their “off the books” activities. Hence they were the biggest stations:

“Under Ted Shackley‘s leadership from 1962 to 1965, JMWAVE grew to be the largest CIA station in the world outside of the organization’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia, with 300 to 400 professional operatives (possibly including about 100 based in Cuba) as well as an estimated 15,000 anti-Castro Cuban exiles on its payroll. The CIA was one of Miami’s largest employers during this period.” (115)

Image from https://spotterup.com/jmwave-the-secret-cold-war-cia-station-in-miami/

Image from https://sandiegocitynewsandtruehistories.com/2018/07/10/sunshine-assassination-secrecy-how-the-cia-made-florida-a-cold-war-battleground-chapter-2/

Image from https://randompixels.blogspot.com/2014/06/the-way-we-werethe-cia-in-1960s-miami.html

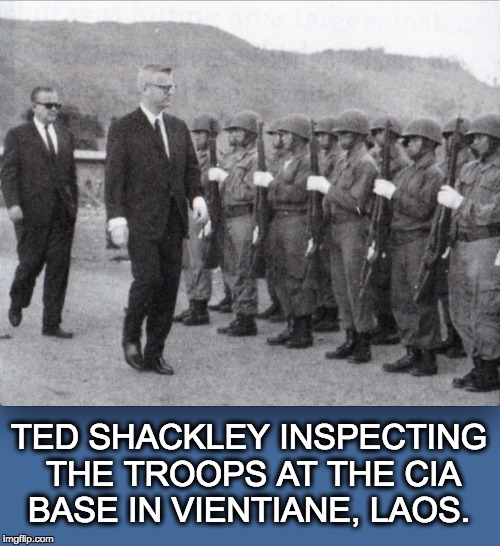

“CIA case officers and Laotian generals, 1968, From left to right: Tony Poe (CIA; dark glasses), Jon Randall (CIA), Gen. Vang Pao (Vaj Pov) (Commander, Military Region II), Howard Freeman (CIA; bearded), Theodore Shackley (CIA Station Chief), and Gen. Ouan Rattikone (Commander-in-chief, Royal Lao Armed Forces), with the CIA officers to receive the Order of the Million Elephants and the White Parasol — Laos’ highest knighthood order — from King Savang Vatthana.” Image from https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/A7AEHNNQYI65WM8B

Image from https://asiatimes.com/2018/01/revolutionary-monument-cias-fall-laos/#

Image from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/ravens-of-long-tieng-284722/

Let’s follow Shackley’s career – it seems to cross paths quite often with Bush’s. First we should start with the Miami CIA station. Why all the focus on Miami? It was all due to Fidel Castro, who kicked the mob out of Cuba and screwed up Mafia/CIA trafficking operations – not to mention CIA sugar plantations and their take from the Casinos. The CIA wanted their drug route back. Miami was their base of operations on that particular project.

Cuba Libre

“To choose one’s master is not to be free.” – Jose Marti

“Fidel had few fans in the mob. It had lost $100 million a year when he took it’s Cuban casinos, brothels, and drug trade away.” – Alex Von Tunzelmann, Red Heat, 2011 (116)

“Fidel Castro’s revolution in Cuba naturally put a dent in that (drug) trade, though it never ceased entirely.” – The Cocaine Wars, Paul Eddy with Hugo Sabogal and Sara Walden, 1988 (117)

The Cuban revolution of 1959 – like most but not all revolutions – was one boss replacing another boss – one gang replacing another gang. The Cuban anarchist and national hero of Cuba – Jose Marti – (whom both the communists and capitalists claim for themselves but whom wouldn’t be caught dead with either) would argue that

“We are free, but not to be evil, not to be indifferent to human suffering, not to profit from the people, from the work created and sustained through their spirit of political association, while refusing to contribute to the political state that we profit from. We must say no once more. Man is not free to watch impassively the enslavement and dishonor of men, nor their struggles for liberty and honor.” (118)

Jose Marti on the Cuban 1 Peso bill – this one from 1953. Image from https://en.numista.com/catalogue/note219508.html

Nevertheless, Fidel Castro managed to convince most Cubans to trade the exploitation of capitalism for the slavery of communism, and many Cubans benefitted somewhat by an increased standard of living and were thankful to trade in one set of rulers for another, despite the obvious disadvantages of the elimination of all political and economic freedoms for the politically and/or economically independently-minded people.

And the mob – who valued independence above all other considerations – the mob wasn’t happy at all. They lost their Disneyland.

Havana’s casinos, brothels and drug smuggling had been mainly controlled by legendary mob boss Meyer Lansky – and to a lesser extent the Trafficante family.

“It was Lansky who opened up what was for a time the syndicate’s greatest source of income, gambling in Havana. He alone handled negotiations with dictator Fulgencio Batista for a complete monopoly of gambling in Cuba. Lansky was said to have personally deposited $3 million in a Zurich, Switzerland bank for Batista and arranged to pay the ruling military junta, namely Batista, 50 percent of the profits thereafter.” (119)

This version of events is echoed in other works. For example, in David Southwell’s encyclopedic The History of Organized Crime, the arrangement is expanded on further:

“When Batista returned to power in Cuba in 1952 after a coup d’état, Meyer approached him with a plan to transform the island into a major tourist destination. Meyer and his Mafia friends would take over all the casinos and racetracks in Cuba, clean them up and promote them as a gambling Mecca to Americans. In return for a free rein in this and other rackets, they would pump money into building luxury hotels and modernizing Havana. Then Meyer opened up a suitcase containing $6 million in cash for Batista. . . . When his regime collapsed, Lansky, Trafficante and many other Mob bosses lost millions in investments as Castro closed the casinos and the residents of Havana went on a slot machine smashing rampage in revenge against those known for being good friends of Batista.” (120)

Santo Trafficante at San Souci’s bar. Havana, Cuba, 1955. Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santo_Trafficante_Jr.

Image from https://themobmuseum.org/blog/the-havana-conference/

Tourists and Cubans gamble at the casino in the Hotel Nacional in Havana, 1957. Meyer Lansky, who led the U.S. mob’s exploitation of Cuba in the 1950s, set up a famous meeting of crime bosses at the hotel in 1946. Ralph Morse, LIFE Picture Collection. Image from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/mob-havana-cuba-culture-music-book-tj-english-cultural-travel-180960610/

I think by “other rackets” they meant brothels and drug smuggling. According to one source, the mob controlled “gambling” as well as

“real estate … luxury hotels and casinos … the traffic in drugs, jewels, the currency exchange, white slavery and pornographic films.” (121)

According to this same source;

“The New York Times had estimated the Mob’s annual gambling take from Cuba at between $350 and $700 million. It was not surprising, therefore, that Castro’s distaste for the Mob was vociferously reciprocated.” (122)

A most accurate snapshot of Castro’s interactions with the Mafia could be obtained from the tell-all book Doublecross by mob bosses Sam (Mooney) Giancana and Chuck Giancana;

“We helped the CIA get guns to Castro, thinkin’ the guy would repay us by goin’ easy on our business down there. But Castro, the lousy bastard . . . I gotta hand it to him . . . he can’t be bought. He says Americans are all crooks and pimps. He’s a fuckin’ double-crosser if there ever was one.”

“But he’s pretty accurate in his view of Americans, don’t you think?”

“Yeah, Castro’s no dummy,” Mooney conceded. He sighed. “So, the CIA finally woke up to the fact that Castro’s closin’ down American business. The government doesn’t like that kind of shit. . . . After all, the CIA’s lost their cut of the take from the casino’s too.” (123)

Every source says much the same thing. The support for Castro provided by the CIA and Mafia pre-revolution was also mentioned by Barry Seal and David Ferrie (see part 1), which explains why – initially – the Mob wasn’t worried about Castro and didn’t fight against the revolution (they thought Castro was on their side), and why so many pro-Batista Cubans turned into the CIA’s Miami army (they felt totally betrayed and wanted revenge).

There were quite a few potential anti-Castro soldiers to choose from. Henrik Kruger’s 1976 book The Great Heroin Coup provides insight into the magnitude of the Miami Cuban community;

“With Fidel Castro’s 1 January 1959 ouster of Batista, Lansky and Trafficante were in trouble. Though they were expelled from their Cuban kingdom, nearly a year elapsed before the Syndicate departed and the casinos were closed. Along with Trafficante and Lansky, half a million Cubans left the island in the years following Castro’s takeover. Some 100,000 settled in the New York City area, especially Manhattan’s Washington Heights and New Jersey’s Hudson County. Another 100,000 headed to Spain, others to Latin America, and a quarter of a million made their new home in Florida, the site of Trafficante’s new headquarters. Out of the Trafficante trained corps of Cuban officers, security staffers and politicians, a Cuban Mafia emerged under the mobster’s control. It specialized in narcotics, first Latin American cocaine, then Marseille heroin.” (124)

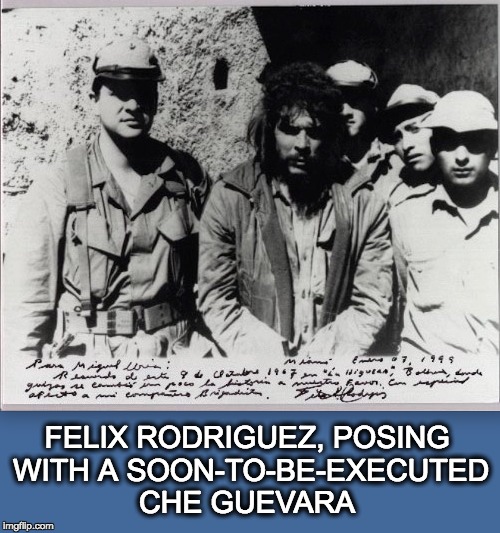

I believe, at this point in our story, it’s time to focus on one of those crooked Cuban cops who turned a blind eye to the Batista/Mafia rackets that would crank out all those profits. I’m talking about a man named Felix Rodriguez, who’s career was very similar to Ted Shackley’s career and Barry Seal’s career in that it followed George Bush to the Bay of Pigs, the Golden Triangle, Iran Contra and nearly everywhere in between.

Image from https://www.bayofpigsbrigade2506.com/infiltration-2

Felix Rodriguez and the war in the shadows

In Felix Rodriguez’s book Shadow Warrior, Rodriguez denied knowing Bush back in his days of Bush being the head of the CIA during 1975-1976. (125) According to at least one researcher, the Rodriquez/Bush relationship went back a decade and a half before then;

“In 1959 (Felix) Rodriguez was a top cop in Cuba under Batista. When Batista fled to Miami Rodriguez went with him, along with Frank Sturgis and Chi Chi Quintero. Officially Rodriquez didn’t join the CIA until 1967, well after both the CIA invasion of Cuba in which he participated, and the assassination of JFK. But records recently uncovered show he actually joined the CIA in 1961, when he was recruited by a certain fella’ named Bush, which is, Rodriguez says, how he became such a ‘close personal friend of Bush.'” (126)

Bush in 1959 – becoming interested in the international oil game just as Castro took over Cuba. Image from https://x.com/WorldOil/status/1070392436118220802?lang=bg

Bush was considered to be a CIA recruiter in Miami by more than one researcher. Russ Baker states;

“In his memoirs, former Cuban intelligence official Fabian Escalante asserted that Nixon had met with an important group of Texas business businessmen to arrange outside funding for the operation. Escalante … claimed that the Texas group was headed by George H. W. Bush and Jack Crichton.” (127)

Alex Constantine quotes John Simkin saying much the same thing;

‘The CIA put millionaire and agent George Bush in charge of recruiting exiled Cubans for the CIA’s invading army; Bush was working with another Texan oil magnate, Jack Crichton.” (128)

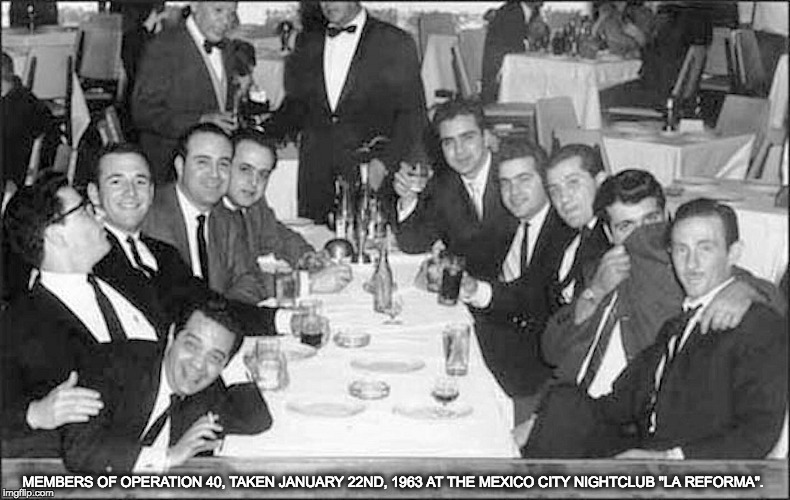

Felix Rodriguez joined a special group inside Bush’s anti-Castro army – a group called “Operation 40” – an elite group of assassins;

“Operation 40, in approximately 1960, was supplemented by a political assassination unit, which was formed specifically to locate and murder Fidel Castro, Raul Castro and Che Guevara.” (129)

Unlike much of this story (which remains hidden away amongst the shadows) a bunch of these spies and assassins were all photographed together in one incredibly illuminating and incriminating photograph. (130) Barry Seal kept a photograph of Operation 40, taken January 22nd, 1963 at the Mexico City nightclub La Reforma. The photo contained;

- CIA agent Felix Rodriguez, front left.

- Porter Goss (future head of the CIA under George W. Bush) sits next to him.

- CIA agent and pilot Barry Seal is immediately behind them.

- Fifth from the left is CIA agent Juan Restoy – a notorious drug smuggler.

- On the far right sits CIA agent William Seymour

- and the man behind Seymour – hiding his face – is said to be either CIA agent Frank Sturgis or CIA agent Tosh Plumlee.

All were under the direct command of CIA agent E. Howard Hunt. Seymour, Sturgis and Hunt were also tied to the Kennedy assassination, and Sturgis and Hunt were also arrested in the Watergate break-in.

Many of the recruits to Operation 40 were hand-picked by José Sanjenis Perdomo, said to also be the doorman at the Dakota on December 8, 1980, the day Beatle John Lennon was assassinated. (131) There is more to be said about Perdomo and Lennon later on in this story.

Rodriguez ended up boasting about achieving one of Op 40’s stated goals: catching and participating in the execution of Che Guevara. Rodriquez even had a picture taken with Che right before Che’s execution. He stole Che’s watch from another soldier, (132) and still wears it to this day. (133)

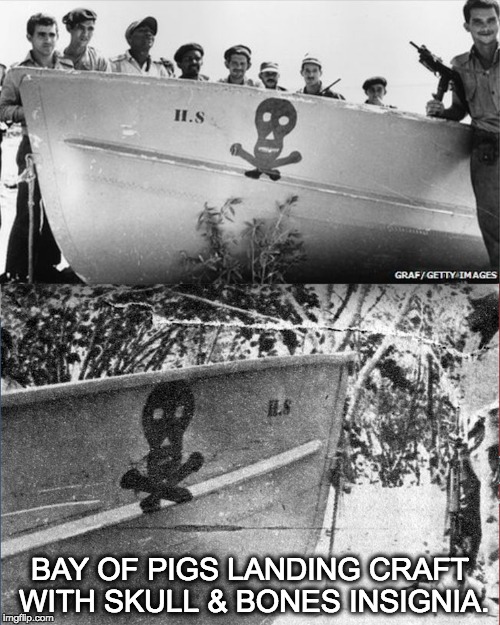

The Bay of Pigs: a Skull & Bones operation

Bush’s role wasn’t limited to recruitment – he and his Skull & Bones brothers were planning and executing the entire invasion of Cuba! The “constellation of evidence” on this fact is pretty massive:

“The new papers of reincorporation that erased the century-old Russell Trust Association were filed at 10:15 a.m. on April 14, 1961. Two hours later, at noon on that day, the orders went out to begin the Bay of Pigs operations–the covert C.I.A.-financed invasion of Castro’s Cuba, a bloody fiasco that still haunts us four decades later. Coincidence? Probably. But then it’s also true that one of the C.I.A.’s masterminds for the Bay of Pigs was a man named Richard Drain, Skull and Bones ’43. And the White House planner of the Bay of Pigs operation was McGeorge Bundy, Skull and Bones ’40. And the State Department liaison for the Bay of Pigs operation was his brother William P. Bundy, Skull and Bones ’39. And the man who filed the reincorporation papers that erased the Russell Trust Association from existence on the day of the Bay of Pigs was Howard Weaver, Skull and Bones ’45 (George Bush’s class), who retired from the C.I.A. in 1959. All of which might lead one to suspect that the Skull and Bones corporate shell had been used as a clandestine conduit of funds for the Bay of Pigs, and then erased from existence to cover up the connection as the invasion got underway.” (134)

It wasn’t just his frat that connected Bush to the Bay of Pigs invasion. His Dad also had major investments on the island:

“Bush’s father Prescott Bush (Skull & Bones 1917) and uncle George H. Walker (Skull & Bones 1927) both lost millions in sugar plantation investments to Castro’s revolution.” (135)

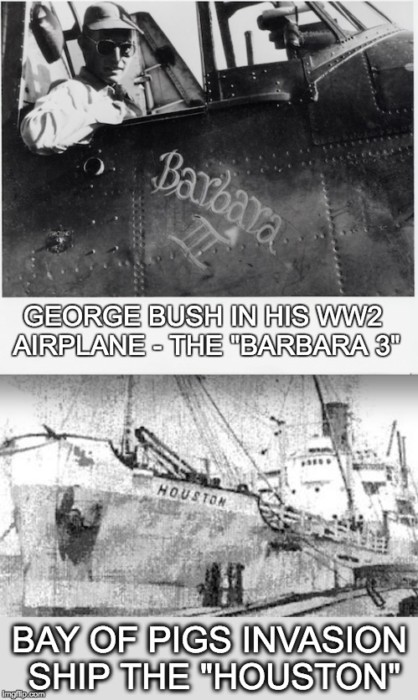

And it wasn’t just the Bonesmen everywhere or his father’s investments, it was the naming of the operation and the naming of two of the ships;

“According to reliable sources and published accounts, the CIA code name for the Bay of Pigs invasion was Operation Zapata, and the plan was so referred to by Richard Bissell of the CIA, one of the plan’s promoters, in a briefing to President Kennedy in the Cabinet Room on March 29, 1961. Does Operation Zapata have anything to do with Zapata Offshore? The run-of-the-mill Bushman might respond that Emiliano Zapata, after all, had been a public figure in his own right, and the subject of a recent Hollywood movies starring Marlon Brando. As J. Hugh Liedtke had observed, he was the classic figure for the revolutionary-cum-bandit. A more knowledgeable Bushman might argue that the main landing beach, the Playa Giron, is located south of the city of Cienfuegos on the Zapata Peninsula, on the south coast of Cuba. Then there is the question of the Brigade 2506 landing fleet, which was composed of five older freighters bought or chartered from the Garcia Steamship Lines, bearing the names of Houston, Rio Es of Houston, Rio Escondido, Caribe, Atlantic, and Lake Charles. In addition to these vessels, which were outfitted as transport ships, there were two somewhat better armed fire support ships, the Blagar and the Barbara. (In some sources Barbara J.) 8 The Barbara was originally an LCI (Landing Craft Infantry) of earlier vintage. Our attention is attracted at once to the Barbara and the Houston, in the first case because we have seen George Bush’s habit of naming his combat aircraft after his wife, and, in the second case, because Bush was at this time a resident, booster, and Republican activist of Houston, Texas. But of course, the appearance of names like ‘Zapata,’ Barbara, and Houston can by itself only arouse suspicion, and proves nothing.” (136)

Newspaper reporter Drew Pearson wrote in the syndicated May 6th, 1961 column “Washington Merry-Go-Round” that the Barbara J was named by skipper “G.C. Jullian” after his wife. But Pearson was known as one of the journalists who co-operated with the CIA in “Operation Mockingbird”. (137)

Image from https://www.bayofpigsbrigade2506.com/naval-force-1

Image from https://www.bayofpigsbrigade2506.com/naval-force-1

Image from https://www.bayofpigsbrigade2506.com/naval-force-1

Image from https://www.bayofpigsbrigade2506.com/naval-force-pt-3

Image from https://www.ozon.ru/product/operation-zapata-the-ultrasensitive-report-and-testimony-of-the-board-of-inquiry-on-the-bay-of-pigs-714332584/

Combine the Skull and Bones evidence, Prescott Bush’s Cuban investments, the ship naming and the fact that Bush’s off shore oil rig was often situated near where the many anti-Cuban operations begin – the island of Cay Sal (138) – it’s a safe bet to say Bush was in on the invasion. This pile of evidence is made even taller when you add evidence connecting Bush to “the Cubans” & “the Texans” mentioned by Nixon and Hoover, as well as connecting Bush to Seal, Rodriquez and other members of Operation 40. This evidence is explored in the following chapters.

The big myth of the Bay of Pigs invasion was that the invasion failed because Kennedy refused to send in air cover. The reality – explained in detail by high-level participant L. Fletcher Prouty (Chief of Special Operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff 1962-1963) – was that one of the Skull & Bones member close to Kennedy – McGeorge Bundy – sabotaged the invasion by insisting that the air cover not arrive until after the securing of a nearby landing strip. (139)

This was against the plan approved by JFK, who allowed some slow-flying B-26’s to attack Cuba’s tiny air force at the start of the invasion – a few crappy planes that supporters could believe were part of the Cuban rebel forces and not the US Air Force. The military were convinced that – with no air cover, the invasion force would be in trouble, and Kennedy would be forced to send in the entire US military, who were already waiting and ready to invade in case the assassins sent for Castro were successful. But the assassins screwed up. And Kennedy didn’t fall for the trap.

Kennedy’s refusal to be tricked into invading Cuba pissed off the Mafia, who wanted their casino’s brothels and drug supply lines back in operation. It pissed off the CIA, who wanted their drug supply lines and other investments back in operation. The CIA sure didn’t appreciate Kennedys firing the top three guys in charge of the Bay of Pigs invasion at the CIA – Dulles, Cabell and Bissell. And Kennedy was beginning to show signs of going soft on those who threatened the supply side of the French Connection – the areas in Laos that grew the opium in the first place. The French Intelligence services were – by late 1963 – losing control of the opium smuggling lines, and it looked to the CIA like Kennedy might treat Vietnam like he treated Cuba – he might have been lying to his military about refusing to pull out entirely “without victory”. This is an assumption, but not entirely without evidence.

Juan Restoy and Operation Eagle – that’s a lot of coke

After the CIA had their first ever defeat – one of America’s only military defeats – at the Bay of Pigs, what happened to their invading army? Evidence suggests over 100 of them went to work becoming the biggest drug traffickers in US history:

“On June 21, 1970, agents of the federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD) arrested 150 suspects in cities around the country. The agency termed it ‘the largest roundup of major drug traffickers in the history of federal law enforcement.’ Attorney General John Mitchell announced at an unprecedented morning press conference that the Justice Department had just broken up ‘a nationwide ring of wholesalers handling about 30 percent of all heroin sales and 75 to 80 percent of all cocaine sales in the United States.’ The syndicate smashed in ‘Operation Eagle’ was remarkable not only for it’s size but also for it’s composition. As many as 70 percent of those arrested had once belonged to the Bay of Pigs invasion force unleashed by the CIA against Cuba in April 1961. The bust gave a hint of evidence that would accumulate throughout the coming decade of the dominance of the U.S. cocaine and marijuana trade by intelligence-trained Cuban exiles. Chief among those arrested in Eagle was Juan Restoy, a former Cuban congressman and member of Operation 40, an elite CIA group formed to size political control of Cuba after the Bay of Pigs landing.” (140)

The Miami News, Aug 26, 1970 · Page 55

Even more interesting than the scope of the operation was that the main organizer of it all was killed in circumstances similar to another member of Operation 40 – Barry Seal – in that he threatened to blow the whistle on the drug smuggling operation and then was shot immediately after:

“Juan Restoy, on the other hand, turned to blackmail. He threatened to expose a close friend of President Nixon’s as a narcotics trafficker, if not given his freedom and $350,000. Restoy was shot and killed by narcotics agents…” (141)

Dead whistleblowers seem to be a re-occurring theme in CIA drug history.

The Miami Herald, Oct 19, 1970 · Page 29

Utopiates

Between 1962 and 1963, Kennedy was smoking pot and taking LSD and tripping balls with his peacenik/artist/mistress/true love Mary Pinchot Meyer, who was attempting to use these drugs as an opportunity to get Kennedy out of the rut of cold-war thinking and turn him towards world peace.

On July 16th, 1962, Mary Pinchot Meyer smoked cannabis with JFK. The event was recorded in Peter Janney’s book “Mary’s Mosaic”:

“Mary produced ‘a snuff box with six marijuana cigarettes’ in Jack’s bedroom. ‘Let’s try it,’ Jack reportedly said to Mary. ‘She and the President sat at opposite ends of the bed and Mary tried to tell him how to smoke pot,’ Truitt was quoted saying in the 1976 National Enquirer article. ‘He wouldn’t listen to me,’ Mary told Truitt. ‘He wouldn’t control his breathing while he smoked, and he flicked the ashes like it was a regular cigarette and tried to put it out a couple of times.’ ‘Mary said that at first JFK didn’t seem to feel anything, but then began to laugh and told her: ‘We’re having a White House conference on narcotics here in two weeks!’ She said that after they smoked the second joint, Jack leaned back and closed his eyes. He lay there for a long time, and Mary said she thought to herself, ‘We’ve killed the President.’ But then he opened his eyes and said he was hungry. He went to go get something to eat and returned with soup and chocolate mousse. They smoked three of the joints and then JFK told her: ‘No more. Suppose the Russians did something now!’” (142)

JFK’s use of LSD had some very interesting timing to it. It was in May of 1963 that Pinchot Meyer was tripping on LSD with – according to her biographer – JFK;

In May of 1963, Meyer told Tim Leary that “My friends and I have been turning on some of the most important people in Washington.” (143)

It was also in May of 1963 that Kennedy came up with the idea for his “American University Speech” – regarded as “one of Kennedy’s finest and most important speeches”. (144)

In May 1963, the president informed his National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy that he wished to deliver a major address on peace. According to Special Assistant Ted Sorensen the speech was kept confidential in fear that the unprecedented tone would “set off alarm bells in more bellicose quarters in Washington” and allow political attacks against Kennedy in advance of the speech. (145)

Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_University_speech

Kennedy painted a picture of a world without war. This vision was attractive to all … except those who depended on war for massive profits – the “military industrial complex” Kennedy’s predecessor Eisenhower warned America about as just as he left office. The content of the speech seems inspired, to say the least.

“What kind of peace do I mean and what kind of a peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave. I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living, and the kind that enables men and nations to grow, and to hope, and build a better life for their children—not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women, not merely peace in our time but peace in all time. … For in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s futures. And we are all mortal.” (146)

President John F. Kennedy’s “Peace Speech”

President John F. Kennedy’s “Peace Speech”

Perhaps coincidentally, the term “utopiate” was coined around this time by Dr. Richard Blum of Stanford University (who also coincidentally worked with the CIA) (147) – a word which meant “drugs which create images of utopia”. (148)

This author’s personal experience with LSD leads him to believe that LSD can interrupt day to day routines and conventional thinking, force one to contemplate the big picture for six to eight hours, and in the proper setting (being among people who value peace, love and happiness, for example) an LSD trip can inspire a person to visions of world peace. It is very likely that this is what happened to Kennedy, with his American University speech being the end result.

Image from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/mary-pinchot-meyer-jfk-mistress-assassinated_n_1434191

In Noam Chomsky’s 1993 book “Rethinking Camelot”, Chomsky argues that Kennedy was lying to the American people when he spoke of world peace and was telling the truth to his generals – he would not pull out of South Vietnam without victory. (149) I think the opposite could be true – he was lying to his Generals (who had lied to him about the Bay of Pigs invasion, he must have realized by then) and was telling the truth to the American People. He did, after all, disappoint the US Army and the right wing when it came to the Cuban invasion. Perhaps he would disappoint them again in Vietnam. It’s reasonable to suspect that’s what the military industrial complex was thinking, in any case.

Kennedy’s combination of 1) refusing to invade Cuba – angering the CIA and their partners the Mafia – with 2) permanently threatening the profits of the military industrial complex with the “world peace” outlined in his American University speech must have been too great of a threat to the true powers that be. This road to world peace, unfortunately, took a wrong turn when it passed through Dallas, Texas on November 22nd, 1963.

Part 2: Chapter 2: CIA’s greatest hits vol. 1: the early sixties

“Only cooperating command elements within the CIA, Army Intelligence, the National Security Agency and the FBI had the reach to coordinate what actually happened at Dallas and during the Warren Commission cover-up – and protection of the geopolitical power financed by the international drug trade was at the very heart of it.”

– Drug War, Dan Russell, 1999 (150)

The CIA had a habit of killing (or attempting to kill) world leaders who stood in the way of their drug operations. It wasn’t just Cuban revolutionaries Fidel Castro and Che Guevara the CIA were gunning for – arguably the assassinations of General Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic on May 30th, 1961 and of Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam on November 2nd, 1963 (20 days before JFK was shot) also follow this pattern. Take Trujillo, for example:

“It is well-established that beginning some time around 1959, the CIA contracted with organized crime to assassinate particular foreign heads of state. What is not generally recognized is that, not at all coincidentally, those foreign heads of state were often in countries key to the CIA-Mafia drug traffic. Prime targets were Cuba’s Fidel Castro, who survived numerous attempts on his life, and the Dominican Republic’s Rafael Trujillo, killed in 1961. After Castro took over Cuba and closed the island to mafia activity, the Dominican Republic became a staging point for a CIA-sponsored invasion of Cuba, as well as a new transit point for Trafficante’s narcotics traffic. Henrik Krüger writes: ‘Furthermore, the CIA, according to agents of the BNDD [Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs], helped organize the drug route by providing IDs and speed boats to former Batista officers in the Dominican Republic in charge of narcotics shipments to Florida.’ (Krüger 1980:145) President Rafael Trujillo may have done something to get in the way of the drug traffic, for the CIA-mafia alliance marked him for death and he was assassinated in May 1961, just after the CIA’s failed invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs.” (151)

The other major example relevant to this discussion is Diem, and those the CIA chose to replace him.

Diem – the other November 1963 assassination

Ngo Dinh Diem was the president of “South Vietnam” between 1955 and 1963. The CIA had rigged the election of 1955 for Diem. (152)

Diem and his family began as anti-drug crusaders:

“During her brother-in-law’s (Diem’s) presidency, Madame Nhu pushed for the passing of ‘morality laws’ outlawing abortion, adultery, divorce, contraceptives, dance halls, beauty pageants, boxing matches, and animal fighting, and closed down the brothels and opium dens.” (153)

… but the realities of funding a police state made it impossible to rule without drug profits funding the secret police, so three years after his war on drugs was initiated, Diem’s complicity in drug running began.

“Shortly after the Binh Xuyen gangsters were driven out of Saigon in May 1955, Diem, a pious Catholic, launched a determined anti-opium campaign by burning opium-smoking paraphernalia in a dramatic public ceremony. Opium dens were shut down, addicts found it difficult to buy drugs, and Saigon was no longer even a minor transit point in international narcotics traffic. However, only three years later the government suddenly abandoned its moralistic crusade and took steps to revive the illicit opium traffic. The beginnings of armed insurgency in the countryside and political dissent in the cities had shown Ngo Dinh Nhu, Diem’s brother and head of the secret police, that he needed more money to expand the scope of his intelligence work and political repression.” (154)

Particularly involved in the illegal drug trade was Diem’s brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, head of the secret police,

Particularly involved in the illegal drug trade was Diem’s brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, head of the secret police,

“… Ngo Dinh Nhu, continued to funnel his American-supplied Laotian opium to the world market through Saigon, Bangkok and Hong Kong. The Golden Triangle opium/heroin trade remained the financial mainstay of the Saigon regime long after the November 1, 1963, CIA-engineered demise of the transparent, and increasingly independent, Ngo Dinh brothers.” (155)

and his other brother, Ngô Đình Cẩn, dictator of “Central Vietnam” and in control of the secret police and army there.

Cẩn was widely believed to be selling rice to North Vietnam on the black market, as well as organizing the trafficking of opium throughout Asia via Laos, and monopolizing the cinnamon trade. (156)

Conein the barbarian

Many have speculated as to the exact reason Diem was killed. Basically it boils down to his ineffective and PR-nightmare-laden repression of the Buddhist community in Vietnam (which included world-famous protests by Buddhist monks who set themselves on fire to draw attention to the repression). That and a little too much “independence” – the CIA preferred their puppet government with a few more strings attached.

Image from https://archive.org/details/fussell-james-a.-conein…-lucien-conein.-kansas-city-star-kansas-city-miss.-sep/mode/2up?view=theater

The responsibility for engineering Diem’s assassination fell mostly on the CIA, particularly two men who’s reputations are forever tied to drug trafficking. The first was the notorious Loucien Conein. By 1963, Conein had already experienced a long career with the CIA, and worked along side many of this story’s main characters:

“In 1951, Gordon Stewart, the CIA chief of espionage in West Germany, sent Conein to establish a base in Nuremberg. The following year Ted Shackley arrived to help Conein with his work. … In 1954 Conein was sent to work under General Edward Lansdale in a covert operation against the government of Ho Chi Minh in North Vietnam. … Joseph Trento has also pointed out that Conein worked with Ted Shackley and William Harvey at the JM/WAVE CIA station in Miami in 1963.” (157)

There is ample evidence of Conein’s involvement in the Diem assassination.

“Toward the end of October of 1963, the ubiquitous Lou Conein was given funds to disperse to insurgent generals. The coup proceeded, and on November 2, 1963, Diem and his brother were killed.” (158)

“The CIA also provided $42,000 in immediate support money to the plotters the morning of the coup, carried by Lucien Conein, an act prefigured in administration planning Document 17). The ultimate effect of United States participation in the overthrow of Ngo Dinh Diem was to commit Washington to Saigon even more deeply. Having had a hand in the coup America had more responsibility for the South Vietnamese governments that followed Diem.” (159)

“From 1973 until 1984, Mr. Conein ran secret operations for the Drug Enforcement Administration. Much about these missions remains secret, although Mr. Conein became a public figure of sorts in 1975 by candidly testifying about his role in the Diem killing to a Senate committee investigating the United States role in the assassination of foreign leaders.” (160)

Image from https://spotterup.com/lucien-conein-from-oss-to-cia/

Very interestingly, Conein kept his role of assassinating those “key figures” tied up in the drug trade for at least a decade … and he did so using some more of the CIA’s anti-castro-Cuban secret out-of-work army:

“In 1972 Conein had been appointed by Nixon to the Drug Enforcement Agency’s Special Operations Group to set up an international network to smash the drug trade, and he proselytized a group of Cubans who had fought against Castro into a unit code-named Deacon 1. It was said that Conein’s methodology included plots to assassinated key international drug figures.” (161)

This quote seems to echo other statements in this section – that the CIA was busy killing the drug dealers who weren’t on their team, or were but were bad at their job. In the eyes of the CIA, JFK qualified either way.

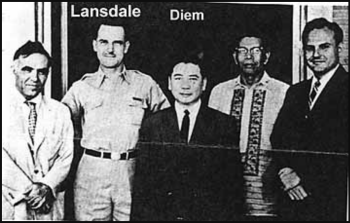

And then there’s Conein’s more famous partner in crime – General Edward Landsdale.

Lansdale with CIA Director Allen Dulles and United States Air Force Chief of Staff General Nathan F. Twining and CIA Deputy Director Lieutenant General Charles P. Cabell at the Pentagon in 1955. Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Lansdale#/media/File:Colonel_Edward_Lansdale_at_The_Pentagon_in_1955.jpg

General Edward Lansdale – retired at exactly the right time

Conein was assisted by Edward Lansdale – the man who put Diem into power back in 1955 with a rigged election. There is much evidence tying Lansdale to CIA drug operations – including the elimination of the CIA’s main competition in the Golden Triangle – French Intelligence and the Corsicans:

“In 1955 CIA agent General Edward Lansdale began a war to liquidate the Corsican supply network. While Lansdale was cracking down on the French infrastructure, his employer the CIA was running proprietaries, like Sea Supply and Cat, that worked hand-in-hand with the opium-smuggling Nationalist Chinese of the Golden Triangle, and with the corrupt Thai border police. The Lansdale/Corsican vendetta lasted several years, during which many attempts were made on Lansdale’s life. Oddly enough, his principal informant on Corsican drug routes and connections was the former French Foreign Legionnaire, Lucien Conein, then of the CIA. Conein knew just about every opium field, smuggler, trail, airstrip, and Corsican in Southeast Asia. He spent his free time with the Corsicans, who considered him one of their own. Apparently they never realized it was he who was turning them in.” (162)

“Lansdale’s resume included experience in an array of political and psychological warfare operations that involved drugs. In 1953, he had viewed the vast Laotian opium fields, and in 1955, he had chased the French out of Saigon and installed the Catholic Ngo regime. The Ngo regime’s own drug smuggling operation was directed by Diem’s brother Nhu (an opium smoker) through his secret police chief, Dr. Tran Kim Tuyen. (Ky’s First Transport Group was at Tuyen’s disposal and shuttled Tuyen’s drug couriers between Laos and Saigon from 1956 until 1963.) In 1960, Lansdale had investigated SDECE’s involvement in drug smuggling, and in 1962 he’d employed drug smuggling Mafiosi in the CIA’s shadow war against Cuba and its KGB advisors. Possessed of a wild imagination, Lansdale had even proposed the introduction of cheap marijuana as a way of undermining Cuba’s economy.” (163)

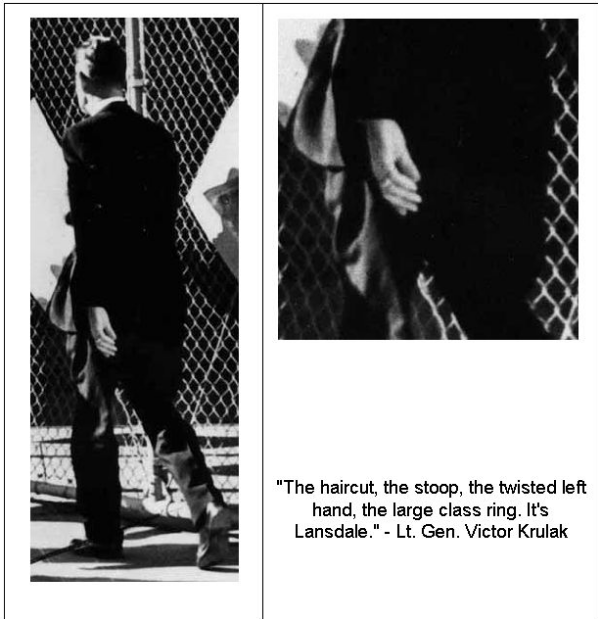

Lansdale – according to multiple researchers – was also one of the planners of JFK’s assassination, and was identified in some of the photos taken that day in Dealey plaza. (164) Coincidentally – or perhaps not – Lansdale retired the day of the Diem Coup – three weeks before Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas. (165)

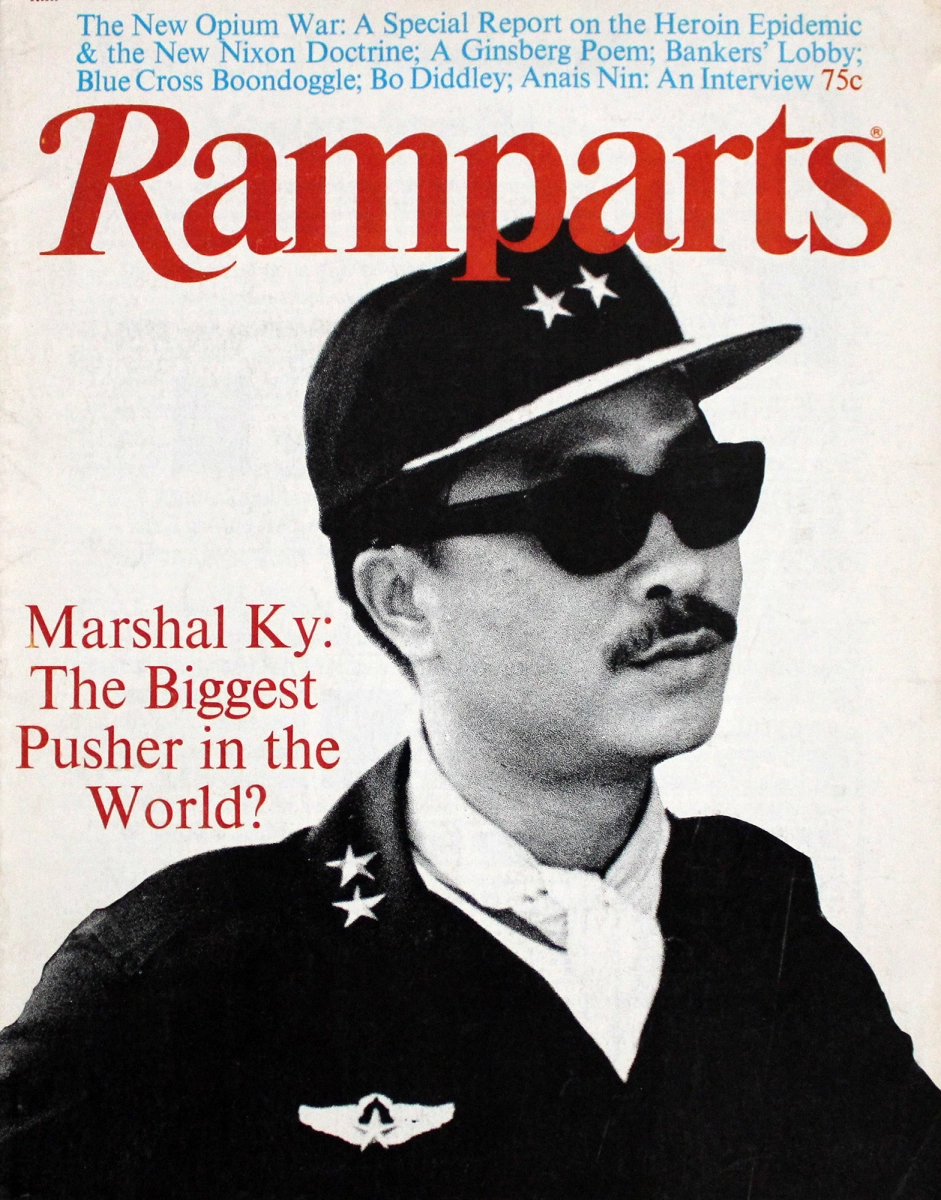

General Nguyễn Cao Ky – the most famous drug pusher of 1971

One of those involved in the 1963 CIA Coup and assassination of Diem was General Ky of the Vietnamese Air Force. (166)

Kỳ began his association with the American covert operations community in 1961. While still ranked as a major commanding Tân Sơn Nhứt Air Base, he became the first pilot for South Vietnam’s presidential liaison officer, which was organizing to infiltrate military intelligence teams into North Vietnam. He recruited pilots from his command for this intelligence program of the Central Intelligence Agency, and flew some of the missions himself after being trained by an expert pilot from Air America. (167)

When General Ky assumed control of Vietnam in 1965, his involvement in the opium trade was so “routine that it had lost almost all of it’s adventure and intrigue.” (168)

“When the Diem administration was faced with large-scale insurgency in 1958, it reverted to the Binh Xuyen formula, and government clandestine services revived the opium trade with Laos to finance counterinsurgency operations. Faced with similar problems in 1965, Premier Ky’s adviser General Loan would use the same methods.” (169)

By May of 1971, Ky was on the cover of “Ramparts” magazine next to text asking the question “Marshall Ky: The biggest pusher in the world?”

Ramparts, May 1971 Image from https://www.wolfgangs.com/vintage-magazines/ramparts/vintage-magazine/OMS783706.html

It is clear that by November of 1963, the CIA put their favorite drug pusher into power in Vietnam through an assassination, and were not above killing world leaders who were not their preferred drug pushers. This is important to keep in mind when looking at CIA involvement in JFK’s assassination.

Was Kennedy viewed by the CIA as just another politician who was getting in the way of their action, who needed to be “whacked”? What evidence exists for the CIA’s involvement in the assassination? And more importantly for this particular telling of the story, is there any connection between the CIA’s involvement in the Kennedy assassination and the CIA’s involvement in drug trafficking? If you look closely at the careers of those involved, the theme of “drugs, guns, assassinations and secret armies conducting secret wars” seems the constant.

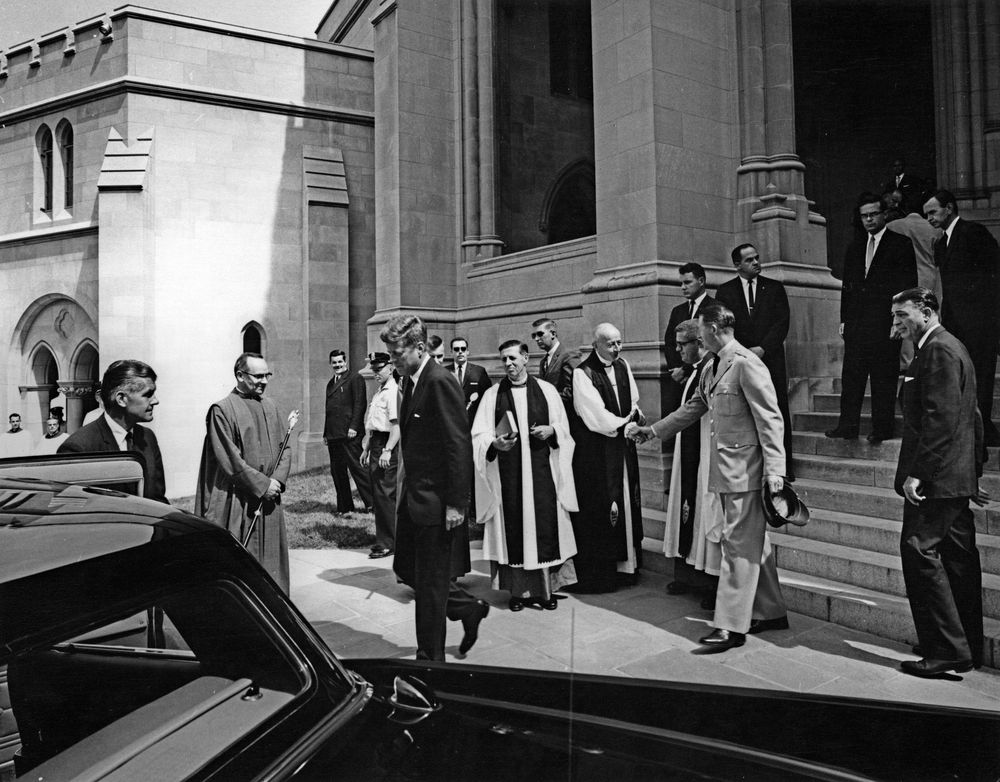

Image from Newsday, (Nassau Edition), August 7th, 1963, p. 48

“Memorial services for publisher and businessman Philip Graham at the National Cathedral, 3:00PM.” 6 August 1963, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston. Image from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_John_F._Kennedy_Attends_Memorial_Services_for_Publisher_and_Businessman,_Philip_Graham.jpg

Image a detail from the image directly above. Take note of the hairline of the frowning man, far right. Bush should have been at Graham’s funeral – Graham was an initial investor in Bush’s oil company when he began Zapata Oil back in 1953. (George Bush – the unauthorized biography, Tarpley & Chaitkin, 1992, p. 145, The Family, Kelly, 2004, p.128) See also the suspicious circumstances surrounding Graham’s death. (Mary’s Mosaic, Janney, 2012, pp. 265-270)

Part 2 Chapter 3: Dallas

Where was George?

The most bizarre claim made by George Bush in regards to the JFK assassination was that he didn’t remember where he was when he heard about it. If this was true he would have been one of the only Americans who did not have this moment engrained into their memory – what makes his claim even more unlikely was that he was a member of the opposing political party to Kennedy and it was in his state where the assassination took place – his life revolved around Texas politics and he can’t remember where he was when Kennedy was killed? For real? In his 2009 book “Family of Secrets”, Russ Baker looks into this astonishing claim in detail. (170).

Several bits of evidence that are relevant to this question have arisen since 1963.

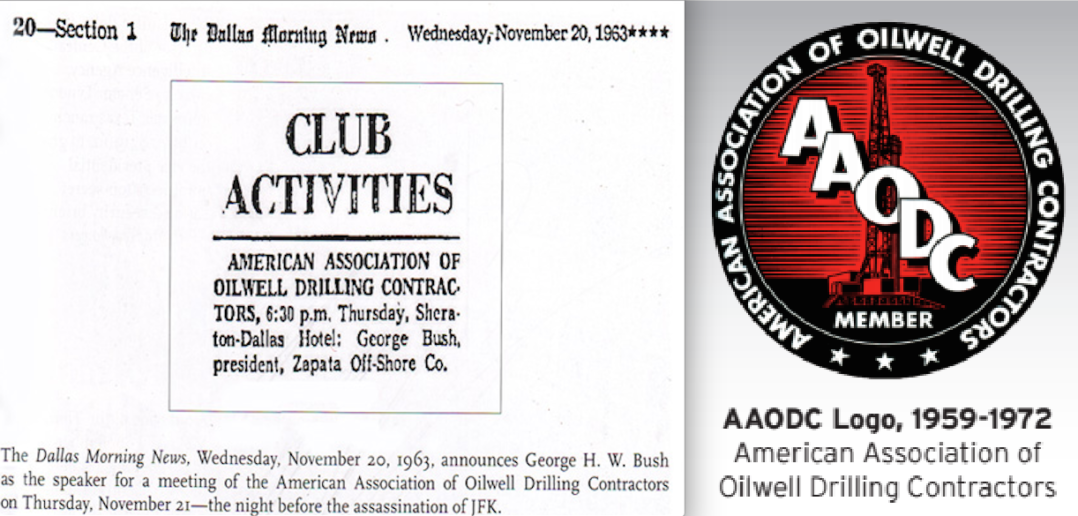

A newspaper announcement in the Dallas Morning News from November 20th, 1963, puts Bush at the Sheraton-Dallas Hotel the night before, speaking at the American Association of Oilwell Drilling Contractors. (171) If Bush was spotted in Dallas that day, he had an excuse as to why he was there.

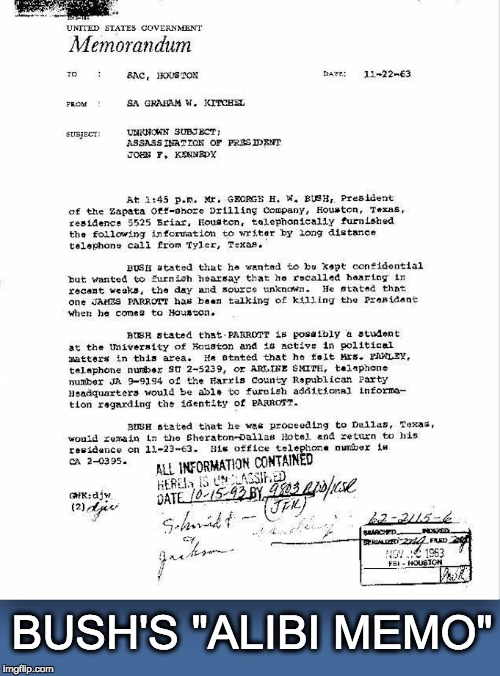

Then there was the “Bush Alibi Memo”. Kennedy was shot at 12:30pm. At 1:45pm – just an hour and fifteen minutes after the shooting, George Bush phones in a red-herring tip about hearsay evidence about an innocent man to the Houston FBI, to establish that he was in Tyler, Texas, a small town 97 miles Southeast of Dallas. (172) A Comanche 250 – one of Barry Seal’s airplanes at the time – had a top cruise speed of 185 miles per hour, so Tyler Texas was about 30 minutes away by small aircraft.

Bush, talking in Tyler, Texas, about one and a half hours after the JFK assassination on November 22nd, 1963.

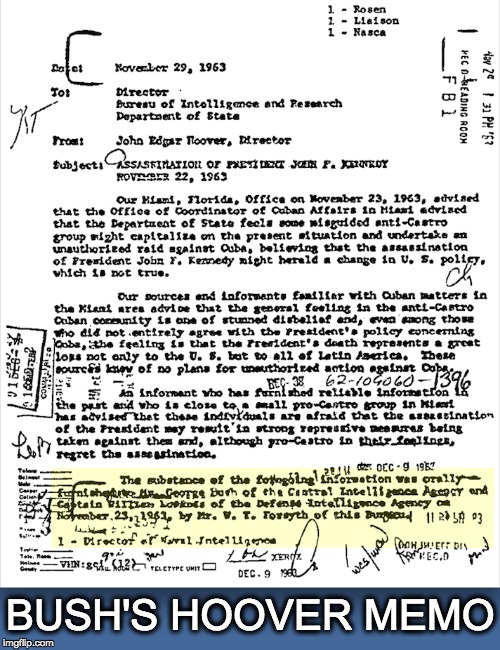

Then there was the “J. Edgar Hoover Memo” – dated November 29th, 1963. It concerned the FBI director passing on the concerns of the Miami FBI, that “some misguided anti-Castro group might capitalize on the present situation and undertake an unauthorized raid against Cuba” – passing on this concern to “Mr. George Bush of the Central Intelligence Agency”. (173)

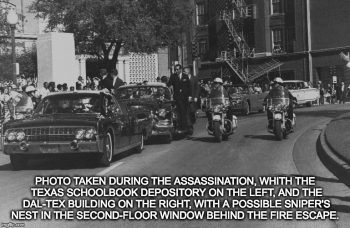

Then there was the strange coincidence of the un-named Texas Oil Man caught running out of the Dal-Tex building, and arrested only due to the “clamor of the onlookers”:

“At least one man arrested immediately after the shooting had come running out of the Dal-Tex Building and offered no explanation for his presence there. Local authorities hardly could avoid arresting him because of the clamor of the onlookers. He was taken to the Sheriff’s office, where he was held for questioning. However, the Sheriff’s office made no record of the questions asked this suspect, if any were asked; nor did it have a record of his name. Later two uniformed police officers escorted him out of the building to the jeers of the waiting crowd. They put him in a police car, and he was driven away. Apparently this was his farewell to Dallas, for he simply disappeared forever.” (174)

Image detail from https://www.jfk.org/collections-archive/image-3-from-negative-strip-25-dealey-of-police-officers-outside-the-front-entrance-to-the-texas-school-book-depository/

“Jim also asked me about the arrests made in Dealey Plaza that day. I told him I knew of twelve arrests, one in particular made by R. E. Vaughn of the Dallas Police Department. The man Vaughn arrested was coming from the Dal-Tex Building across from the Texas School Book Depository. The only thing which Vaughn knew about him was that he was an independent oil operator from Houston, Texas. The prisoner was taken from Vaughn by Dallas Police detectives and that was the last that he saw or heard of the suspect.” (175)

Image from https://quadriv.wordpress.com/2011/10/15/graham-greene-edward-lansdale-and-audie-murphy/

Given these factors derived from the evidence above:

- 1) Bush doesn’t remember where he was when he found out.

- 2) Bush was in Dallas the night before.

- 3) The Bush Alibi Memo puts Bush within range of the assassination.

- 4) The Bush Hoover Memo outs Bush as CIA and places him amongst Cuban anti-Castro, anti-Kennedy elements.

- 5) That someone matching his description got arrested running out of a possible sniper’s nests.

- 6) That Bush was coordinating assassination groups for the CIA since 1961.

- 7) That Bush felt betrayed by Kennedy for a) messing with the CIA’s and the Bush family’s investments in Cuba and b) refusing to use US troops to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs.

To top it all off, 8) some researchers believe Bush’s eldest son and future president George W. Bush – then 17 years old – can also be seen in photos from that day, walking in front of the Dal-Tex building, looking for his Dad, who was probably being questioned by police at the time. (176) It must have been “bring your son to work day” at the CIA that day.

To that list we must add 9) – that one of Bush’s oil buddies and old friends was Oswald’s CIA handler – George De Morensheldt.

According to Bush himself, Bush and de Morensheldt met in the “early 40’s” as an uncle to a school roommate at Andover. (177) Russ Baker makes a compelling case that de Morensheldt was a CIA agent. (178)

Image from https://whowhatwhy.org/politics/government-integrity/bush-and-the-jfk-hit-part-5-the-mysterious-mr-de-mohrenschildt/

Image from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/85704602/george_sergius-de_mohrenschildt

De Morensheldt wrote then CIA director Bush in 1976, complaining about being followed and having his phone tapped. Baker p. 67 Shortly after that de Morensheldt was found dead in his home, his head blown off by a shot gun, ruled a suicide. (179)

When 9 coincidences tie you or me or some regular, not-too-powerful person to the murder of an unexceptional victim, there’s usually an investigation of such a person. If it’s the president of the United States and there’s no investigation into Bush’s role in the assassination given the 9 coincidences, something fishy is going on with the US justice system.

You don’t know Jack Ruby

Jack Ruby seemed to know many of those associated with the assassination of JFK. He was a gangster who worked for Santo (sometimes spelled “Santos”) Trafficante Jr. and Carlos Marcello. He knew members of the FBI and CIA. He knew both Castro and the anti-Castro Cubans, and ran guns to both. And he knew Lee Harvey Oswald. (180)

Like Bush, Lansdale, Rodriguez, Trafficante, Marcello, Ferrie and Seal, he seemed to have been deeply involved in the drugs/guns/assassinations world.

Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa and Santos Trafficante cooperated in smuggling drugs into the United States, with Teamsters Local 320 in Miami being one of the fronts for the business (Krüger 1980:143). Chicago mobster David Yaras, who answered to Sam Giancana, had assisted Hoffa in organizing Local 320, where Trafficante kept an office (Scott 1993:175). Jack Ruby of Dallas reported to Yaras and was another of Giancana’s men, involved in drug trafficking as well as gambling, arms smuggling, and operating a strip club. The CIA was aware of Ruby’s drug smuggling activities, according to former anti-Castro operative Robert Morrow, who worked under the CIA’s Tracy Barnes. Barnes was one of the Bay of Pigs planners, perhaps the most high-ranking one to have survived the Kennedy post-invasion firings. According to Morrow, Barnes said that one of Ruby’s arms smuggling partners was also one of the Agency’s ZRRIFLE assassins and that Ruby was taking advantage of that fact, counting on the CIA to remain silent on the smuggling for fear of exposing the assassination program (Morrow 1992). As one of the CIA-connected men who had supplied Castro with arms before he came to power and subsequently fell from favor with the U.S., Ruby is thought to have negotiated Trafficante’s release from Castro’s prison (Giancana 1992:279; Marrs 1989:394-98). … Ruby had been the subject of investigation by federal narcotics agents as early as 1947, for suspected involvement in a scheme to fly opium over the border from Mexico (Scheim 1983:117). It may have been as a result of this investigation that Ruby first became a federal informant. In 1947, an FBI staff assistant in Congressman Richard Nixon’s office wrote a memo asking Ruby to be excused from testifying before congress on the grounds that Ruby was “performing information functions” for the Congressman’s staff (Marrs 1989:269). (181)

And like many involved in the JFK assassination, he died of mysterious circumstances. More on that in a future chapter.

Part 2: Chapter 4: The Vietnam Drug War

Billy Covington:

“Business? I was just getting used to this being a war.”

Major Donald Lemond:

“Who told you they were two different things?”

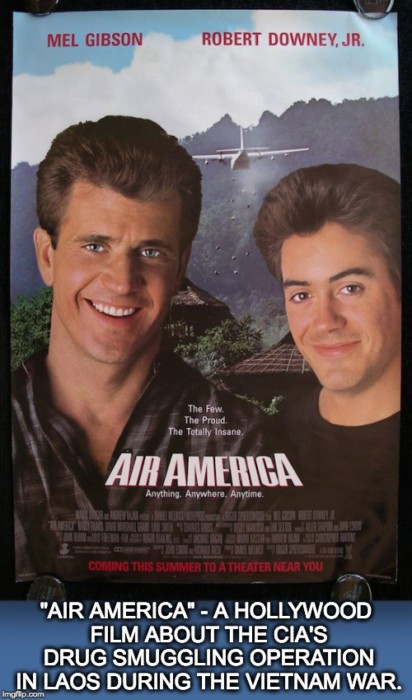

– Air America, a 1990 film about the CIA opium/heroin operation in Laos.

“According to former CIA Director William Colby, ‘The CIA has a solid rule against being involved in drug trafficking. That’s not to say that some of the people whom the CIA has used … over the years may well themselves have been involved in drug trafficking, but not the CIA.’ Colby should know – from 1959 to 1972 he oversaw most major U.S. intelligence operations in the Vietnam Theater, undertaken in support of a series of drug-corrupted South Vietnamese leaders like Ngo Dinh Diem, (1955-63), Nguyen Cao Ky (1965-67) and Nguyen Van Thieu (1968-75). Diem’s brother Ngo Dinh Nhu, head of South Vietnam’s secret police, guaranteed safe conduct for the Corsican-run Air Laos Commerciale to ship opium from Laos to Vietnam. Nhu used his profits to expand the scope of the secret police’s power. After Diem’s CIA-sponsored 1963 assassination, Ky became commander of the Vietnamese Air Force which, in two years, displaced the Corsican airline as the prime mover of Laotian opium. Ky also ‘taxed’ opium shipments through his control of both the Vietnamese Customs Service and the Saigon Port Authority. Thieu’s intelligence chief, General Dang Van Quang, was by 1971 ‘the biggest pusher in South Vietnam,’ according to NBC Saigon correspondent Phil Brady. Colby became CIA director in 1973. In 1976, he formally retired, but soon became a lawyer for the Australian-based, CIA-connected Nugan Hand Bank. There he joined forces again with several men previously under his command in Vietnam – Theodore Shackley, Thomas Clines, Richard Secord and the bank’s co-founder, Michael Hand.”

– Paul Brancato, “The Vietnam (Drug) War”, Drug Wars Trading Cards, 1991 (182)

The Vietnam war was a great way for corporate America to make a buttload of cash. If the US defeated the Vietnamese, the defeated faced a loss of control of their off-shore oil prospects replaced with export-agriculture and raw material extraction and high-repression, low wage jobs. If America lost, at least there would be weapons sales, military supplies, planes, helicopters, fuel sales and (for the CIA) drug smuggling. By the early 1970’s, some researchers were catching on to the drug smuggling, and writing about it in the alternative press:

“Who are the principles in this new opium war? The ubiquitous CIA, whose role in getting the U.S. into Vietnam is well known but whose pivotal position in the opium trade is not. … According to the United Nations Commission on Drugs and Narcotics, since at least 1966 80 percent of the world’s 1200 tons of illicit opium has come from Southeast Asia.” (183)

“Many big parts of the Indo-China War (such as that strange little war in Laos) are merely political excuses for territorial fights between opium overlords. It has been claimed many times that the government of South Vietnam and the American C.I.A. are both in the opium business up to their eyebrows …” (184)

Later scholarship confirmed the pervasiveness of the drug smuggling going on in Vietnam, and hints at Bush’s awareness of it all:

Relations between Bush and Perot had gone downhill ever since the Vice President had asked Ross Perot how his (Vietnam war) POW/MAI investigations were going. “Well, George, I go in looking for prisoners,” said Perot, “but I spend all my time discovering the government has been moving drugs around the world and is involved in illegal arms deals. … I can’t get at the prisoners because of the corruption among our own covert people.” This ended Perot’s official access to the highly classified files as a one-man presidential investigator. (185)

“Unstated activities” in Laos

According to his son and future President George W. Bush;

“The day after Christmas 1967, Congressman George Bush embarked on a sixteen-day trip through Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand. He met with senior American officials. He also spent time with junior officers and enlisted men…” (186)

Image from https://www.businessinsider.com/president-george-hw-bushs-life-long-dedication-to-the-us-military-2018-12

Image from https://www.bush41.org/exhibits/permanent

If one were to speculate as to which “senior American officials” and “junior officers and enlisted men” Bush went to visit, one might consider he left with another CIA agent – Thomas Devine. And there were lots of CIA agents in that part of the world that Bush was likely to have hung out with. According to investigative journalist Russ Baker;

“In December 1967, less than a year after Bush was sworn in (to Congress) he was off to Indochina, with his CIA partner Thomas Devine in tow. It was Christmas break, a time when congressmen often make overseas trips, but Bush and Devine did not have a typical agenda. Correspondence indicates that having arrived in Vietnam, Bush and Devine hastily canceled an appointment with the U.S. ambassador in favor of other, unstated activities. For the CIA, the hot item at the time was the so-called Phoenix Program, a secret plan to imprison and ‘neutralize’ suspected Vietcong. This was being rolled out at precisely the moment that Poppy and Devine arrived ‘in country.’ By the time CIA director William Colby admitted to the program in July 1971, more than twenty thousand people had been killed – many of them possibly innocent, officials later concluded. One person involved in Phoenix’s early stages was Felix Rodriguez, a Cuban exile and CIA operative. Rodriguez would go on to become a great friend of Poppy Bush’s, even visiting him in the White House. If J. Edgar Hoover’s 1963 memo was correct in mentioning ‘George Bush of the CIA’ as an intermediary with Cuban exiles, the coincidence of Rodriguez’s activities in Vietnam with that of Bush’s visit raises questions as to how the two were connected. In 1970 Rodriguez joined the CIA front company Air America, which allegedly played a role in trafficking heroin from Laos to the United States. The Laotian operation was led by Donald Gregg, who would later serve as national security adviser during Poppy Bush’s presidency. When Bush and Devine traveled to Vietnam the day after Christmas 1967, Devine was in his new CIA capacity, operating under commercial cover. Handwritten notes from the trip show that Poppy was especially interested in the Phoenix program, which he referred to by the euphemism ‘pacification.’ The two remained in Vietnam until January 11, 1968.” (187)

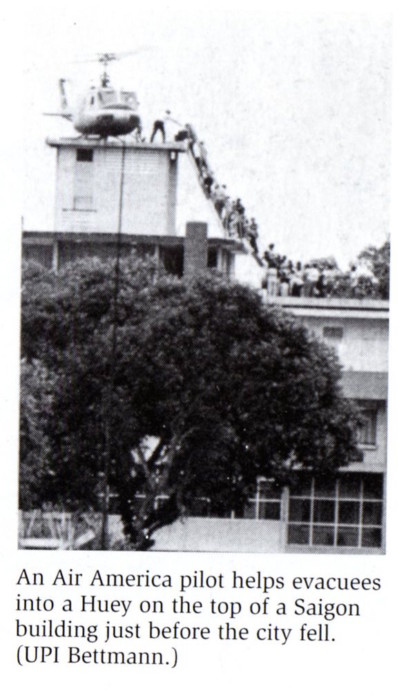

Image from Air America, Christopher Robbins, Asia Books, Bangkok, 4th edition, second printing, 2002, between pages 170 and 171.

Secret teamwork makes the secret dream work

“Whether or not the Secret Team had anything to do with the deaths of Rafael Trujillo, Ngo Dinh Diem, Ngo Dinh Nhu, Dag Hammarskjold, John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and others may never be revealed … “ (188)

– L. Fletcher Prouty, The Secret Team, 2011

Spending more time on the topic of “who might Bush have been meeting up with in Southeast Asia” is also a who’s who of what Fletcher Prouty calls “the Secret Team”. Some “Secret Team” participants in 1960’s-1970’s Southeast Asia connected to Bush:

Richard Armitage

A Navy “advisor” in Vietnam, a number of researchers link Armitage to the CIA and drug trafficking in Southeast Asia. (189) Later he became Reagan’s “Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Policy” and did things like meet with Noriega. (190) Bush kept him busy with that and then running bases in Thailand, and tried to get him a job in the Defense Department but he withdrew his nomination while under investigation by the FBI. He later became famous for outing fellow CIA agent Valerie Plame. (191)

Ted Shackley

Before 1965 he was the CIA station chief for JM/Wave – the biggest CIA base outside of Langley, Virginia. “JM” was a CIA cryptonym for “Cuba”. The base was located on the University of Miami campus. The base was closed down in 1965 after it was discovered that the base was used to organize drug smuggling. (192) Shackley was then moved to Vientiane, the capital of Laos, to run the now-largest CIA base in the world. Shackley has been linked to drug trafficking by many researchers. (193)

Thomas Polgar (far right) takes command of the CIA station in Saigon, January 1972. At left is former Station Chief Ted Shackley, heading back to a new assignment in Washington. In the middle is General Creighton Abrams, head of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV). Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Shackley

Thomas Polgar (far right) takes command of the CIA station in Saigon, January 1972. At left is former Station Chief Ted Shackley, heading back to a new assignment in Washington. In the middle is General Creighton Abrams, head of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV). Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Shackley

Image from https://x.com/hugoturner1969/status/1761150086179110944/photo/1

Image from https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/3405341/raven-forward-air-controllers/

Image from https://alchetron.com/Golden-Triangle-(Southeast-Asia)

Shackley was accused of heroin smuggling in Laos by Lt. Col. James Gordon “Bo” Gritz in 1987 in Congress:

“According to Khun Sa, Shackley was a major player in the opium trade in the years 1965-1975. During part of this time, Shackley was the head CIA man in Vietnam and Laos. According to Khun Sa, Shackley was also the head of the US involvement in the narcotics trade in Southeast Asia at this time.” (194)

In May 1976, Shackley was made Deputy Director of Covert Operations by CIA director Bush. Later, Shackley becomes Bush’s speechwriter in the 1979-1980 election campaign. (195) He later found himself to be the originator of the “arms for hostages” part of the Iran Contra scandal, famously suggesting a “discussion of a quid pro quo that involved items other than money” – because, you know, cash for hostages looks so much worse in the public eye than weapons (or drugs) for hostages.

Image from https://www.flickr.com/photos/31597114@N02/2961084914/in/photostream/

The Daily Telegraph, Dec 27, 2002 · Page 33

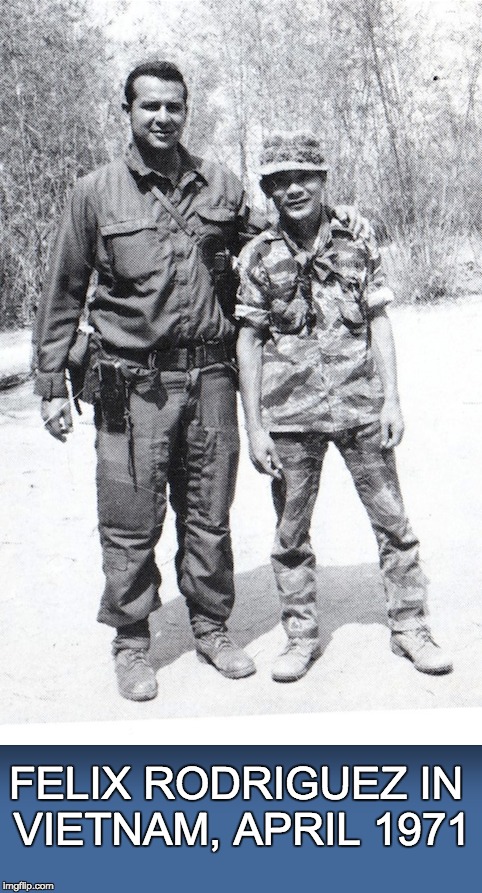

Felix Rodriguez

In his 1989 autobiography – “Shadow Warrior” – Rodriguez claims he went to Vietnam in 1970 and never mentions Laos or Vientiane or Air America or Ted Shackley. The Christic Institute claims Rodriguez was in Laos with Shackley. (196) Rodriguez only mentions the Christic Institute in passing – as a “left wing” organization that he definitely didn’t leak information to – and does not mention their accusations against him. (197) Rodriquez claims to have been in Ecuador and Peru between 1968 to 1970 (198) but then again, he also claims that he was never involved in drug trafficking (199).

Barry Seal

Not much information exists about Barry Seal in Vietnam – even in the book about him. But there is a few short passages about his experience in Southeast Asia, including this one;

“Then these men, ‘Barry and ‘the boys,’ all go off to Southeast Asia. Laos was where they went: because Laos was where the money was. ‘Barry was not a soldier of fortune or a mercenary – he was a covert operative. It was the 1970’s when I saw Barry again.’ Says friend ‘Red’ Hall, delivering a bombshell. ‘Right after he got caught flying drugs in a 747 out of the Orient during the Vietnam War. He had a lot of government connections: that’s a fact.’ Needless to say, no official record of this, nor many other events in this story, remains.” (200)

Image from High Times, December 2000: https://www.ebay.com/itm/256673139669

Donald Gregg

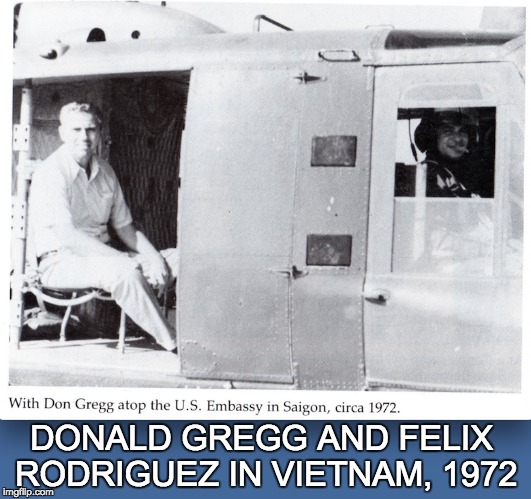

Gregg claims to have been “in charge of the ten provinces around Saigon from ’70 to ’72.” (201) Russ Baker (202) has him in Laos in charge of drug operations with Shackley and Rodriguez. Gregg answered a number of questions in an FBI polygraph examination in 1990. It was judged that he lied in his responses to multiple questions, including: “Have you ever given any false or misleading testimony about Felix Rodriguez to the Grand Jury or the congressional investigating committees?” (203) Greg appears with Rodriguez in Vietnam in photo #16 in Rodriguez’s autobiography: “Shadow Warrior”.

John Singlaub

Not involved in the drug trafficking until later on, he “ran the assassinations arm of the enterprise” and would go on to supply Seal with a “fleet of drug smuggling aircraft” in the 1980’s (204). In his 1991 autobiography “Hazardous Duty”, Singlaub admits to being in Laos in 1966 until 1968 – the same years that Shackley was there (205) – and also admits to being a friend of Ted Shackley (206).

Image from https://www.coffeeordie.com/article/john-singlaub-special-operations-legend

Richard Secord

In his 1992 autobiography “Honored and Betrayed”, Secord admits working with Shackley in Vientiane, Laos, beginning in 1966 – when Shackley arrived (207), and also waxes poetic about the sight of the “lush valley filled with opium poppies waving scarlet in the breeze” that met him when he first got there. (208) The Christic Institute has him “dropping airborne incendiary devices on the jungle caravans of Vang Pao’s opium competitors” and overseeing “the transport of raw opium by Vang Pao’s tribesmen in paramilitary aircraft from the mountain opium fields of the Hmong tribe to locations where it could be processed into morphine base, later to be processed into ‘China White’ heroin” (209)

Image from https://aircommando.org/in-memory-of-maj-gen-richard-secord/

Santos Trafficante

This famous mob boss of Havana and Miami was reported to have first visited Laos back in 1962 (210) and visited again in 1968 to meet with the Corsicans. (211) According to the Christic Institute, Shackley set up a meeting between Trafficante and Vang Pao – the Hmong tribe leader – to “set up a heroin smuggling operation from Southeast Asia to the United States” – continuing the cooperation experienced by Trafficante and Shackely back in Miami in the early 1960’s. (212) Trafficante didn’t bother to write an autobiography, never spent a day in jail, and died of old age. (213)

Edward Lansdale

Major General Edward Lansdale was an OSS/CIA man who used his position in the Air Force as a cover. When he first got to Vietnam in 1953, he discovered opium smuggling by French intelligence, but was told not to interfere by his superiors. (214) In 1955 he attacked the pro-French drug dealing locals. (215) Lansdale extolled the virtues of “Civil Air Transport” – a forerunner of Air America – in a 1961 document that found it’s way into the Pentagon Papers (216). He knew Shackley from as far back as late 1961, when Lansdale’s “Operation Mongoose” began to be run out of Shackley’s Miami base. He retired November 1st, 1963. It was claimed by his associates he could be seen in a photo of Dealy Plaza on November 22nd, right after JFK’s assassination. (217) Lansdale returned to Southeast Asia from 1965 through 1968 and wrote about the “extra legal money-collecting systems” he helped to set up on behalf of Marshal Ky – said by some to be the “Biggest Drug Pusher in the World”. (218) When he returned to Vietnam in 1965, he negotiated a “truce” with the Corsican smugglers, and agreed not to investigate their drug running – a percentage of Corsican drug profits ended up going to Ky. (219)

Image from https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2018/06/07/edward-lansdale-vietnam-meddling-american/

Oliver North

Believe it or not, the famous Oliver North makes an appearance way back in 1965 with the rest of the secret team – and the story involves – of all things – drugs;

“Although North’s 1991 Autobiograph – ‘Under Fire’ – does not mention Laos, a number of writers have placed him there. Dan Russell writes: ‘(Joseph) Califano’s Vietnam era playmates, William Colby, Edward Lansdale, Ted Shackley, Thomas Clines, Edwin Wilson, Lucien Conein, Richard Secord, Richard Armitage, John Singlaub, Felix Rodriguez, Barry McCaffrey and Oliver North, engineers of the Vang Pao-Laotian Opium connection, wen on to engineer Reagan’s Trafficante-supported Contra-Cocaine connection. … Serving under Secord in Laos was Oliver North.’ (Russell, 2000, p. 341) Daniel Hopsicker writes: ‘With Jack Kennedy reduced to a flickering flame over a gravesite in Arlington National Cemetery, ‘the boys’ were firmly in the saddle, and ready to persue their dreams in that section of the planet known as Southeast Asia. They moved to Laos, because that was where the money was, a man who spent over 20 years in Special Forces, who we’ll call Colonel Nick, told us. He’d been stationed in Laos in the mid-‘60’s, he said, in charge of an ‘A’ base in the hills. His job had been to pay hill tribesmen $6 dollars per kilo for their opium. ‘The Chinese only paid $4, and that was how we ‘bought’ their allegiance,’ this Special ops vet told us. ‘And once a month we would pile all the acquired opium down on the end of the dirt runway and burn it in a bonfire. Then, as I recall, some of the guys would run around quick to get downwind. There’s not that much to do in Laos.’

‘Everything changed in early ’65’, Col. Nick said. ‘Then an order came down to burn no more opium, but to ‘store it’ instead, for removal to a more ‘secure’ location.’ That order coincided with Ted Shackley, Oliver North and Richie Secord coming into the theater of operations,’ he stated crisply.” (220)

Needless to say, North plays a much more pivotal role in a future chapter of this comprehensive collection of evidence of CIA drug trafficking – in a little 1980’s scandal known as “Iran-Contra”.

But there’s lots of other topics to cover in this story before we even get there.

Stay tuned for part three, where we figure out how the RFK assassination, the Marilyn Monroe assassination, the MK-Ultra drug experiments, Richard Nixon and Watergate relate to Bush and his collection of spooks, pilots, drug smugglers and hit men you have been reading about in this already pretty effed-up story. It seems very incredible … until you read all the evidence at the same time – then it explains a lot of mysteries and ties up a lot of loose ends. Because if there’s a lesson in all of this hidden history, it’s that “elite deviance” isn’t a conspiracy theory, it’s actually astute institutional analysis – right out of first year sociology. (221)

(109) Ted Shackley, Spymaster: My Life In The CIA, 2005, Potomac Books, Virginia, p. 52

(110) Kitty Kelley, The Family: The Real Story of the Bush Dynasty, 2004, Doubleday, New York, p. 213

(111) Sam & Chuck Giancana, Double Cross, 1992, Macdonald & Co., New York, p. 328

(112) Rodney Stitch, Defrauding America, 1998, Third Edition, Diablo Western Press, Inc., Alamo, California, pp. 375-376

(113) Theodore Shackley, Enigmatic C.I.A. Official, Dies at 75

By DAVID STOUT, DEC. 14, 2002 http://www.nytimes.com/2002/12/14/us/theodore-shackley-enigmatic-cia-official-dies-at-75.html

(114) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unione_Corse https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sicilian_Mafia – see also: “Both Lansky and Luciano were eager to get out of the vulnerable business of heroin production and concentrate on drug sales. Production was assigned to the Guerinis and other Corsican syndicates based in Marseilles. The Corsicans already had a worldwide production network, with labs in Indochina, Latin America and the Middle East. They also enjoyed near perfect political protection. Not only did they have the gratitude of the French right (they had prudently never sold heroin in France) but also the CIA, which had helped make them the most powerful force in Marseilles. Thus was forged the French Connection, whereby 80 percent of the heroin entering the United States via Cuba came from Marseilles with the compliance of US government agencies, primarily the CIA. Between 1950 and 1965 there were no arrests of any executive working in this French Connection. In 1965 a crackdown by the French government prompted a relocation of production to Indochina, where both the Corsican gangsters and the CIA were well entrenched.” Alexander Cockburn & Jeffrey St. Clair, Whiteout – The CIA, Drugs and The Press, 1998, Verso, London and New York, p. 141

(115) Wikipedia, JMWAVE https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JMWAVE

(116) Alex Von Tunzelmann, Red Heat, 2011, McClelland & Stewart, Toronto, p. 181

(117) Paul Eddy with Hugo Sabogal and Sara Walden, The Cocaine Wars, 1988, W.W. Norton and Company, New York, p. 44

(118) Quotations from Martí : Thoughts/Pensamientos (1994) edited by Carlos Ripoll https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Jos%C3%A9_Mart%C3%AD

(119) Carl Sifakis, The Mafia Encyclopedia, 1987, Facts On File Inc., New York, p. 179

(120) David Southwell, The History of Organized Crime, 2006, Carlton Books, Ltd, London, pp. 190-191

(121) David E. Scheim, Contract On America, 1988, Shaplosky Publishers, New York, p. 188

(122) Ibid, p. 189

(123) Doublecross, p. 293

(124) Henrik Kruger, The Great Heroin Coup, updated, 2015, TrineDay, Walterville, Oregon, p. 140 http://quixoticjoust.blogspot.ca/2013/12/the-great-heroin-coup-chapter-15.html

(125) Felix Rodriguez and John Weisman, Shadow Warrior, 1989, Simon & Schuster, New York, p. 265

(126) Daniel Hopsicker, Barry and the Boys, 2001, Mad Cow Press, Eugene, Oregon, p. 167

(127) Russ Baker, Family of Secrets, 2009, Bloomsbury Press, New York, p. 83

(128) John Simkin, quoted in “Jackals: The Stench of Fascism”, Alex Constantine, 2016

(129) Christic Institute, Inside the Shadow Government, 1988, Christic Institute, Washington, D.C., p. 6

(130) Barry and the Boys, p. 507

(131) Warren Hinckle & William Turner, The Fish Is Red, 1981, Harper & Row, pp. 307-308, see also Fenton Bresler, Who Killed John Lennon, 1989, St. Martin’s Press, New York, p. 201

(132) Shadow Warrior, p. 170

(133) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Che_Guevara#Post-execution_and_memorial

(134) Ron Rosenbaum, “I Stole the Head of Prescott Bush! More Scary Skull and Bones Tales,” New York Observer, July 17, 2000 http://observer.com/2000/07/i-stole-the-head-of-prescott-bush-more-scary-skull-and-bones-tales/

(135) Kevin Phillips, American Dynasty, 2004, Viking, New York, pp. 203-206 see also Family Of Secrets, p. 36

(136) Webster Griffin Tarpley, George Bush: The Unauthorized Biography, tarpley.net http://tarpley.net/online-books/george-bush-the-unauthorized-biography/chapter-9-the-bay-of-pigs-and-the-kennedy-assassination/

(137) spartacus-educational.com/JFKmockingbird.htm

(138) Family of Secrets, pp. 34-35

(139) L. Fletcher Prouty, JFK: The CIA, Vietnam, and the Plot to Assassinate John F. Kennedy, 2011, Skyhorse Publishing, Delware, pp. 132-135

(140) Peter Dale Scott and Jonathan Marshall, Cocaine Politics, 1991, University of California Press, Berkeley, pp. 26-27

(141) The Great Heroin Coup, updated, 2015, p. 145 http://quixoticjoust.blogspot.ca/2013/12/the-great-heroin-coup-chapter-15.html

(142) Peter Janney, Mary’s Mosaic, 2012, Skyhorse Publishing, Delware, pp. 225-226

(143) Tim Leary, “The Murder Of Mary Pinchot Meyer”, The Rebel, November 22, 1983, p. 46 See also Mary’s Mosaic, pp. 225, 255-256

(144) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_University_speech

(145) Sorensen, Ted. Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History. Harper-Collins Publishers, New York, 2008 See also: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_University_speech

(146) John F. Kennedy, American University Speech, June 10th, 1963

(147) https://www.almanacnews.com/morgue/2005/2005_02_23.blum.shtml

(148) https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/572204

(149) Noam Chomsky, Rethinking Camelot, 1993, Black Rose Books, NYC, pp. 105-148

(150) Dan Russell, Drug War, 1999, Kalyx.com, Camden, New York, p. 291

(151) Rogue Elephant – The Drug Trade, the Kennedy Assassination, and the War in Vietnam, Kent Heiner (2001) https://www.memresearch.org/econ/rogue.htm

See also page 434 in the CIA’s “Family Jewels” collection:

https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu//NSAEBB/NSAEBB222/family_jewels_full_ocr.pdf

And page 255 of Douglas Valentine’s book Strength of the Wolf (2004, Verso, NYC) and pages 26-27 of Mark Zepezauer’s book The CIA’s Greatest Hits (1994, Odonian Press, Tucson, Arizona) and page 439 of the third edition of “Defrauding America” for more on Trujillo and the CIA.

(152) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State_of_Vietnam_referendum,_1955

(153) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madame_Nhu

(154) Alfred W. McCoy, The Politics of Heroin, 1991, Lawrence Hill Books, Brooklyn, New York, p. 203

(155) Drug War, p. 231