A history of cannabis use for stress and depression – rough copies

These are two rough copies of two pamphlets I’m working on … please let me know what you think, how you think they may be improved and if I’ve missed anything. I’m basically attempting to show that all use is medicinal and that everyone is legitimate and protected by the constitution (we all have a right to medicine – the courts in Canada have affirmed that right).

The “it’s all medical” argument would also nullify the international drug treaties that prohibit all cannabis use except medical use. This would expand the market of the med pot dispensaries to include all users – everyone suffers from stress and depression once in a while. I’ve excluded all non-human studies because I don’t think you can tell much about stress and depression from rats in cages – if I was a rat in a cage I would be stressed and depressed to begin with.

I will publish the pamphlets in down-loadable formats complete with citations once I am satisfied they are as good as they can be. There will be a cannabis harm reduction pamphlet in the series, as well as future pamphlets on performance enhancement, epiphanies, aphrodisiac effects and other often-noted effects that sometimes escape the definition of “medicinal”.

A history of cannabis’s use as an anti-depressant and stimulant

By David Malmo-Levine, 2010

Depression and Fatigue

Depression is defined as an “absence of cheerfulness or hope” (Dorland, 1903), being “low in spirits” (Taber, 1952), an “emotional state of dejection” (Hoerr, 1952), an “undue sadness or melancholy due to no recognizable cause” (Dorland, 1959), “the blues” (Schifferes, 1963), and “extreme feelings of sadness, dejection, lack of worth and emptiness” (Glanze, 1987).

Fatigue is defined as “weariness, usually from overexertion” (Dorland, 1903).

Antidepressants and Stimulants

An “antidepressant” is defined as “a drug or a treatment that prevents or relieves depression” (Glanze, 1987). A “stimulant” is defined as “an agent or remedy that produces … functional activity” (Dorland, 1903).

The long history of cannabis’s use as an anti-depressant and stimulant

Within the long history of cannabis medical literature there are many differing opinions about the risks – and many differing opinions about the causes of those risks – but as to the effects of cannabis, it’s reputation as an anti-depressant and stimulant has remained a constant.

The ancient era

The earliest descriptions of cannabis or hashish (“hashish” or “hasheesh” being an extract of cannabis) being used to treat depression and fatigue come from Clay tablets from 22nd century B.C.E. in Sumer, where cannabis is used for grief or “depression of spirits” (Thompson, 1949). Homer – circa 8th century B.C.E. – wrote of “Nepenthes”, a magical drug which could assuage grief, believed to be cannabis (Robinson, 1946). Herodotus – circa 420 B.C.E. – wrote that the Scythians would “howl with joy” from breathing in cannabis vapors (Able, 1980). Democritus (460-371 B.C.E) the “laughing philosopher” spoke of a plant called “potamaugis” – thought to be cannabis – which was responsible for “immoderate laughter” (Emboden, 1990). Galen (129-216 C.E.) wrote that cannabis was a “promoter of high spirits” (Ratsch, 2001).

Ancient Sanscrit writers speak of “Pills of Gaiety” – a preparation based on cannabis and sugar (Lewin, 1924). Mahsati, a twelfth century Persian poet wrote that eating “a little” hashish does help “against sorrow” (Rarsch, 2001). Twelfth and thirteenth century Egyptian poets indentified “euphoria” as one of the effects of eating hashish (Clarke, 1998). The leader of the Safaviya (sufi order) from 1460-1488 C.E. was the Persian monk Haider – “or Haydar” – who introduced his fellow monks to hashish, “and were transformed from austere ascetics into jolly good fellows” (Robinson, 1946).

In 1563 Garcia Da Orta wrote that cannabis allowed his servants “not to feel their work, to be very happy, and to have a craving for food” (Able, 1980). Captain Thomas Bowrey wrote in 1680 that if a user ingested cannabis when “merry” “he shall continue soe with exceedinge great laughter” (Able, 1980). Linnaeus (1707-1778) stated that cannabis could be used for “chasing away melancholy” making the user feel “happy and funny” (Koerner, 1999). In 1777, Johan Friedrich Gmelin wrote that “Orientals” mixed the cannabis buds with honey to “achieve a pleasant type of drunkenness” (Fankhauser, 2002).

The scientific era

In the modern scientific era (mid 18th century onward) doctors wrote that the effects of cannabis were “of the most cheerful kind, causing the person to sing and dance, to eat food with great relish, and to see aphrodisiac enjoyments” (O’Shaughnessy, 1839). In 1843, Dr. Lay observed that the use of hashish produces glee and cheerfulness in warmer regions, whereas in colder climate of England these effects are not as pronounced (Ley, 1843)

In 1845, Dr. Moreau de Tours wrote in his book Du Hashisch et de L’Alientation Mentale that the effects included “a feeling of gaiety and joy inconceivable to those who have never experienced it” and that it could provide the means “of effectively combating the fixed ideas of depressives” (Russo, 2001). Writers admitted they were “moved to laugh foolishly about the most unimportant matters” (von Bibra, 1855) and spoke “of exquisite lightness and airiness” and “unutterable rapture”, of “bliss of the gods” and “unquenchable laughter” (Taylor, 1855) and of “a strange and unimagined ecstasy” (Ludlow, 1857).

In the October 16th, 1858 and October 18th, 1862 Editions of Harper’s Weekly, a small advertisement for Gunjah Wallah’s Hasheesh Candy promises the user “A most pleasureable and harmless stimulant – Cures Nervousness, Weakness, Melancholy &c. Inspires all classes with new life and energy.”

19th century medical opinion of the effects of cannabis included descriptions such as; “…the face is covered in smiles … it has been proposed by M. Moreau to take advantage of this reputed action, to combat certain varieties of insanity connected with melancholy and depressing delusions.” (Bell, 1857), “some inclination to laugh unnecessarily” (Polli, 1870), and “a sort of revery which is almost always very delightful … voluptuous ecstasy, usually free from a cynic element” (Trousseau, 1880), and “an agreeable exaltation of the mental facilities” (Lyman, 1885) and “pleasure” (Bose, 1894) and “motiveless merriment” (Stille, 1894) and of an effect which “allays morbid sensibility” (Pierce, 1895, 1918).

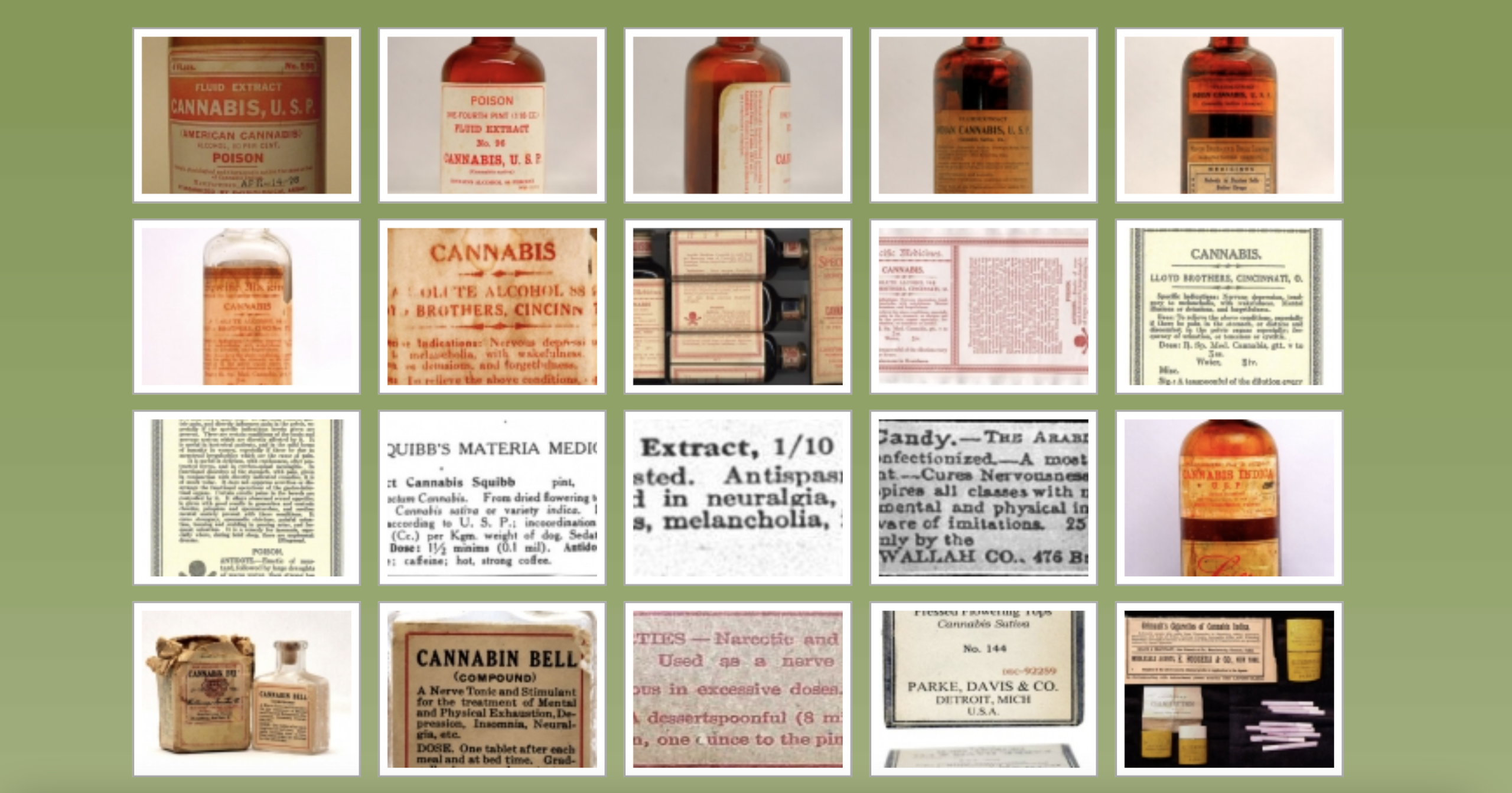

Merck’s 1907 and 1930 Indexes state that cannabis is used for “mental depression”. Dock’s 1908 “Textbook of Materia Medica for Nurses” says that cannabis Indica “causes a mental state of joyous exhilaration.” Blumgarten’s 1932 Textbook of Materia Medica states that the cannabis produces “pleasure and exhilaration “ which leaves the user “usually joyful and happy.” The British Pharmaceutical Codex of 1934 states that cannabis produces “a feeling of happiness”. The editors of the 1935 book Everybody’s Family Doctor states that users may end up “feeling very gay and pleased with everything”.

Lying about the risks but telling the truth about the high

While inaccurate about the risks of cannabis, post-cannabis-prohibition medical textbooks continued to tell the truth about the actual effects of proper cannabis use. The United States Medical Dispensary of 1947 states that “in some persons it appears to produce a euphoria” (Osol & Farrar, 1947). The Modern Medical Counselor states that it “gives its user gay daydreams” (Swartout, 1949). The 1950 Merck Manual lists “giggling” as one of the symptoms of “smoking marihuana”. Solomon describes one of the effects of cannabis use as “euphoria, a feeling of well-being accompanied by a dreamy state, exhilaration” (Solomon, 1952). The Encyclopedia of Family Health stated “marihuana” “cheers the spirits” and makes users “exhilarated with a sense of well-being” (Fishbein, 1959). Merck has continued to use words such as “euphoria” (Merck Index, 1976) and “In general, there is a feeling of well-being, exaltation, excitement, and inner-joyousness that has been termed a “high” (Merck Manual, 1977). “Euphoria” was also mentioned in the 2001 Merck Index.

Government reports

All the important government reports have noted the anti-depressant effects of cannabis use. In 1994 the Indian Hemp Drug Commission reported that cannabis is “the Joy-giver, the Sky-flyer, the Heavenly-guide, the Poor Man’s Heaven, the Soother of Grief…” (Campbell, 1894). The New York Mayor’s LaGuardia Committee reported effects such as “…a sense of well-being and contentment, cheerfulness and gaiety…” (LaGuardia, 1944). The British Wootton Report mentioned “elation” and “euphoria” were two of the effects (Wooton, 1968). The Canadian LeDain Commission reported that “Cannabis is an intoxicant and a euphoriant” (LeDain, 1970). The US Shafer Commission reported “At low, usual ‘social’ doses, the intoxicated individual may experience an increased sense of well-being; initial restlessness and hilarity followed by a dreamy, care-free state of relaxation” (Shafer, 1972). The Canadian Senate recently reported “Low doses generally produce the effects that cause people to like smoking pot. They include mild euphoria, relaxation, increased sociability and a non-specific decrease in anxiety” (Special Committee on Illegal Drugs, 2002).

Cross-cultural use

Hashish confections eaten by the Turks causes them to become “cheerful, to sing, laugh, and to make all kinds of merry follies” (Von Bibra, 1855) Cannabis has been used in central Asia as an antidepressant (Rubin, 1976). An energizing effect is noted by working class males in Jamaica (Rubin, 1976). In Costa Rica, smokers use cannabis as a remedy for depression and malaise (Carter, 1980). The Iroquois use cannabis as a stimulant – they claim “this plant will get you going” (Moerman, 1998) Shamans of Nepal continue to use cannabis for depression to this day (Ratsch, 2001). After a massive review of the historical and cross-cultural evidence of the medicinal use of cannabis, Christian Ratsch writes; “Around the world, hemp is particularly valued as an antidepressant. From a medical perspective, this mood-enhancing ability may be hemp’s most important effect” (Ratsch, 2001). This sentiment was echoed by Dr. Tod Mikuriya, who called cannabis’s ability to fight depression “its most important property” (Gieringer, Rosenthal & Carter, 2008).

Recent Studies

According to researchers studying users in Jamaica, cannabis “makes you feel happy” (Rubin and Comitas, 1976). A study of 17 subjects at Duke University found that cannabis smoking increased depression – but only among inexperienced users (Mathew & Wilson, 1992). A study of 79 psychotics found that those who used cannabis recreationally reported less anxiety, depression, insomnia and physical discomfort (Warner, 1994). A WHO study concluded “There are also reports of an anti-depressant effect, and some patients may indeed use cannabis to ‘self-treat’ depressive symptoms” (World Health Organization, 1997).

In examinations of 2,480 California patients, Dr. Mikuriya found that 27% reported using cannabis for “mood disorders” and another 5% used cannabis as a substitute for more toxic drugs (Gieringer, 2002). Investigating the potential effects of cannabinoids on depression, Musty reports feelings of euphoria but no anxiety from the use of cannabis (Musty, 2002). An internet survey of 4400 adults by researchers at the University of Southern California found that cannabis users reported less depressed mood and more positive affect than non-users (Denson & Earleywine, 2006). A research paper from psychologists and pharmacologists concluded that “major depression” could be associated with an abnormally inactive endocannabinoid (chemicals similar to cannabis that the body produces) system (Hill et al, 2006). An Australian survey of medical cannabis users found that 56% used cannabis for depression (Carter, 2008). Researchers have identified THC (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol) as a primary source of the stimulating, euphoric and antidepressant effects of cannabis (Ratsch, 2001).

Beginning to understand the nuances of cannabis medicine

Cannabis has both relaxing and stimulating effects, based upon many factors including the strain of cannabis and number & ratios of cannabinoids, the health, setting, mindset, and diet of the user, their experience with and tolerance of the various cannabinoids, the quality, potency & purity of the medicine and of course the dose.

In the US National Dispensatory of 1894, it is written that “the plant richest in resin grow at an altitude of 1800 to 2400 M.” and that the effects of cannabis “varies with thin individual’s temperament”. In Cushny’s 1906 “Pharmacology and Therapeutics or the Actions of Drugs” the effects of cannabis are described as “a mixture of depression and stimulation … it’s action … seems to depend very largely on the disposition and intellectual activity of the individual. The preparations used also vary considerably in strength, and the activity of even the crude drug seems to depend very largely on the climate and season in which it is grown, so that great discrepancies occur in the account of it’s effects.”

One text notes “Preparations made from plants grown in warm climates are usually better” (Blumgarten, 1932). Another notes that after two years of storage “it had lost about half it’s potency” (Osol & Farrar, 1947). Still another notes that “Many of the psychological effects seem related to the setting in which the drug is taken”(Merck Manual, 1972). One even noted “an occasional panic reaction has occurred, particularly in naive users, but these have become unusual as the culture has gained increasing familiarity with the drug” (Merck Manual, 1982). Another noted that cannabis’s effects are dependant upon “the dose of the drug and the underlying psychological conditions of the user” (Taber, 1997).

Unfortunately, the prohibition of cannabis had a negative effect on its medicinal reputation. Textbooks began to remark upon the “completely unpredictable” (Faddis, 1943) nature of the drug, or it’s “unreliability” (Dilling, 1933, Merck Index, 1952) in providing consistent results – blaming the drug itself for the researcher’s own inability to understand the proper cultivation of cannabis for medicine, the various strains/cannabinoids and their various effects or the importance of the subject’s mindset and setting. Some textbooks then began omitting entirely any mention of cannabis in their later additions (Pierce, 1935, Blumgarten, 1940). Others began to blame whole-plant cannabis for the effects experienced by one of it’s isolated cannabinoids (Martindale, 1977, Carter, 2008).

Still, the special relationship between cannabis’s prohibition and its reputation was accurately assessed in the 1987 Merck Manual: “…the chief opposition to the drug rests on a moral and political, and not a toxicological, foundation.”

A history of cannabis’s use as a soporific, hypnotic, relaxant, nervine, anxiolytic and sedative

By David Malmo-Levine, 2010

Stress and Anxiety

Stress is defined as “a loading of the nervous system” (Hoerr, 1952) and “any factor that threatens the health of the body or has an adverse effect on its functioning, such as … worry” (Bantam, 1990). A “stress reaction” is defined as “a response to extreme anxiety … treatment for a stress reaction includes the use of drugs to calm the patient …” (Glanze, 1987).

Anxiety is defined as “a feeling of worry, upset, uncertainty, and fear that comes from thinking about some threat or danger” (Glanze, 1987). For “anxiety attack” and “anxiety neurosis”, Glanze indicates “treatment may include drugs and psychotherapy”.

Anxiolytics, Soporifics, Hypnotics, Nervines, Relaxants, Sedatives, and Narcotics.

Taber defines an “anxiolytic” as “a drug that relieves anxiety” (Taber, 1997). Dorland (1903) defines “soporific” as “causing or producing profound sleep”; “hypnotic” as “a drug that produces sleep”; a “relaxant” as “an agent that lessens tension”; a “nervine” as “allaying nervous excitement … a remedy for nervous disorders”; and a “sedative” as “a remedy that allays excitement”. Dorland defines a “cerebral sedative” as “one which particularly affects the brain. To this class belongs cannabis, camphor, the bromids, hyoscin, and the hypnotic and revulsive agents.” Dorland also includes cannabis in a list of the “nerve-trunk sedatives”.

“Narcotic” was originally just another name for a drug which produced “sleep or stupor” (Dorland, 1903, 1959). Some sources list cannabis as one of the primary narcotics (Hoerr, 1952). But in many parts of the medical world the term “narcotic” has come to be associated exclusively with drugs “more powerful than hypnotics” (Taber, 1952) such as opiates and other drugs that produced physical withdrawal symptoms (Glanze, 1987). Cannabis’s withdrawal symptoms are admittedly mild (Merck Manual, 1950, Schifferes, 1963) and therefore the term “narcotic” – now an opiate-specific term (Bantam, 1990) – is no longer appropriate.

The long history of cannabis’s use as a soporific, hypnotic, relaxant, nervine, anxiolytic and sedative

Within the long history of cannabis medical literature there are many differing opinions about the risks – and many differing opinions about the causes of those risks – but as to the effects of cannabis, it’s reputation as a soporific, hypnotic, relaxant, nervine, anxiolytic and sedative has remained a constant.

The Ancient Era

The earliest descriptions of the cannabis or hashish (“hashish” or “hasheesh” being an extract of cannabis) being used to treat stress and anxiety was in ancient Sumer, where cannabis was called the “plant of forgetting worries” (Ratsch, 2001). In the Atharvaveda (cir. 1400 B.C.E.) cannabis (the bhang plant) is mentioned once:

“We tell of the five kingdoms of herbs headed by Soma; may it and kuca grass, and bhanga and barley, and the herb saha release us from anxiety” (Able, 1980).

The Zend-Avesta, written by Zarathustra – also known as Zoroaster – in the seventh century B.C.E. refers to concoctions made from cannabis as Zoroaster’s “good narcotic” (Clarke, 1998). In the famous “Arabian Nights” tales of the middle ages there is the story of King Omar causing Princess Abrizah to fall into a deep sleep using cannabis (Clarke, 1998). Shih-chen included cannabis in his famous 1568 C.E. herbal Pen-ts’ao as a remedy for “nervous feelings” (Ratsch, 2001).

The Scientific Era

As far back as 1843 doctors used cannabis tincture as an anxiolytic, soporific and hypnotic for those suffering from morphine withdrawal (Clendinning, 1843). In the modern scientific era (mid 18th century onward) explorers and doctors mention the effects of cannabis being at first stimulating but then resulting in a “soft and pleasant drowsiness, from which I sank into a deep, refreshing sleep” (Taylor, 1855), a remedy for “sleeplessness” as a “calmative and hypnotic” (McMeens, 1860), a “moderate anodyne and soporific” (Clarke, 1878) and “a prostration that is full of languor and charm” (Trousseau, 1880).

According to reputable medical sources “it is a useful adjuvant, in small doses, to other hypnotic remedies” (Lyman, 1885), it “is well known as a sedative” (Mackenzie, 1887), it “sometimes impaired power of locomotion, the limbs feeling as if weighted with lead” (Stille etc al, 1894), and it “produces sleep” (Pierce, 1895). An advertisement in the May 5th, 1888 Cincinnati Lancet-Clinic for “Grimault’s Cigarettes of Cannabis Indica” mentions “insomnia” as one of the conditions that the cigarettes treat.

Cannabis is listed as a “Sedative, anodyne, hypnotic” in the Squire’s Companion to the British Pharmacopoeia (1899). In Merck’s 1899 manual, “cannabine tannate” is recommended as a “Hypnotic, Sedative” used for “Hysteria, delirium, nervous insomnia”. Cushny (1906) calls cannabis a “hypnotic” and states; “… the symptoms eventually pass into tranquil sleep, from which he awakens refreshed, and, as a rule, without any feeling of depression or nausea.” Merck’s 1907 and 1930 Indexes call cannabis a “Hypnotic; … Nervine; Sudorific …”. McGregor-Robertson (1907) states “Indian hemp is used to relieve pain and produce sleep”. Dock’s 1908 “Textbook of Materia Medica for Nurses” calls cannabis a hypnotic and that cannabis causes “a heavy sleep”. Both the 1908 and1916 edition of the Squire’s Companion to the British Pharmacopoeia calls it a sedative, as does the 1925 edition of Lilly’s Handbook of Pharmacy and Therapeutics. A Parke, Davis & Company 1929-1930 physicians’ catalog lists cannabis as a sedative (Mikuriya, 1973). Blumgarten’s 1932 Textbook of Materia Medica states that cannabis is used to “produce sleep”.

Bruce and Dilling’s Materia Medica and Therapeutics stated it was “formerly” used as a hypnotic which produced effects “ending in a stuporous sleep” (Dilling, 1933). The British Pharmaceutical Codex of 1934 calls cannabis a “sedative or hypnotic”. Dr. Bromberg, a psychiatrist, noted that “the smoker becomes drowsy, falls into a dreamless sleep and awakens with no physiological after effects” (Bromberg, 1934). The editors of the 1935 book Everybody’s Family Doctor calls cannabis a “sleep producing drug”. Cannabis is listed as an ingredient in sedative mixtures in Solomon’s 1935 “Prescription Writing and Formulary”.

Lying about the risks but telling the truth about the high

While inaccurate about the risks of cannabis, post-cannabis-prohibition medical textbooks continued to tell the truth about the actual effects of proper cannabis use Cannabis is listed as a “hypnotic” and “sedative” in the 1940 edition of the Merck Manual. The 1946 pharmaceutical trade journal Ciba Symposia points out that cannabis “is sometimes employed as a hypnotic in those case where opium, because of long-continued use, has lost it’s efficiency” (Robinson, 1946). The United States Medical Dispensary of 1947 states that cannabis is used to “encourage sleep, and to soothe restlessness” (Osol & Farrar, 1947).

Solomon affirmed cannabis “produces sleep” (Solomon, 1952). The Encyclopedia of Family Health stated “marihuana” causes one to be “relaxed” and then experience “drowsiness” (Fishbien, 1959). But by the 1960’s medical textbooks were often using phrases such as “formerly as analgesic and sedative” – the word “formerly” in reference to the newly instituted prohibition rather than any noted change in it’s actual effects (Dilling, 1933, Merck Index, 1960 & 1968, Martindale, 1977). “Drowsiness” was also mentioned in the 2001 Merck Index.

Government reports

The British Wootton Report indicated that “We found a large measure of agreement among witnesses about the principal subjective effects of the drug. Most gave chief emphasis to it’s relaxing and calming effect” (Wootton, 1968). The Canadian Le Dain Commission reported that “it generally acts as a relaxant” (Le Dain, 1970). The US Shafer Commission mentions “a dreamy, care-free state of relaxation” (Shafer, 1972). The Canadian Senate recently reported “Low doses generally produce the effects that cause people to like smoking pot. They include mild euphoria, relaxation, increased sociability and a non-specific decrease in anxiety” (Special Committee on Illegal Drugs, 2002).

Cross-cultural use

In a treatise titled “Indigenous Drugs of India” it is written that “cannabis is used in medicine to relieve pain, to encourage sleep, and to sooth restlessness” (Chopra & Chopra, 1957). According to African people interviewed by ethnobotanists, cannabis helps Africans to “forget all our troubles” (Watt & Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962). In Jamaica cannabis is used to assure a good night’s sleep (Rubin, 1976). In Thailand folk medicine an infusion of cannabis is used as a relaxant (Rubin, 1976). Cannabis is listed in all the official current Chinese pharmacopoeia as – among other things – a sedative (Ratsch, 2001). In Latin American folk medicine Cannabis is smoked for sleep disorders (Ratsch, 2001).

Recent Studies

Researchers have identified the cannabinoids CBD (cannabidiol) and CBC (cannabichromene) as the primary sources of cannabis’s sedative effects (Ratsch, 2001) and anxiolytic, antipsychotic and antischizophrenic effects (Zuardi et al, 2006). A controlled study of 15 insomniacs found that CBD helped subjects sleep better (Carlini & Cunha, 1981). A study of 17 subjects at Duke University found that cannabis smoking increased anxiety in inexperienced users but decreased it in experienced ones (Mathew & Wilson, 1992). A study of healthy normal subjects with induced anxiety found that anxiety was reduced by CBD alone (Zuardi et al., 1993).

A study of 79 psychotics found that those who used cannabis recreationally reported less anxiety, depression, insomnia and physical discomfort (Warner, 1994) Many cannabis buyers club members say they use marijuana as a substitute for prescription narcotics (Gieringer, 1996). In examinations of 2,480 California patients, Dr. Mikuriya found that 27% reported using cannabis for “mood disorders” and another 5% used cannabis as a substitute for more toxic drugs (Gieringer, 2002).

Beginning to understand the nuances of cannabis medicine

Cannabis has both relaxing and stimulating effects, based upon many factors including the strain of cannabis and number & ratios of cannabinoids, the health, setting, mindset, and diet of the user, their experience with and tolerance of the various cannabinoids, the quality, potency & purity of the medicine and of course the dose.

In the US National Dispensatory of 1894, it is written that “the plant richest in resin grow at an altitude of 1800 to 2400 M.” and that the effects of cannabis “varies with thin individual’s temperament”. In Cushny’s 1906 “Pharmacology and Therapeutics or the Actions of Drugs” the effects of cannabis are described as “a mixture of depression and stimulation … it’s action … seems to depend very largely on the disposition and intellectual activity of the individual. The preparations used also vary considerably in strength, and the activity of even the crude drug seems to depend very largely on the climate and season in which it is grown, so that great discrepancies occur in the account of it’s effects.”

One text notes “Preparations made from plants grown in warm climates are usually better” (Blumgarten, 1932). Another notes that after two years of storage “it had lost about half it’s potency” (Osol & Farrar, 1947). Still another notes that “Many of the psychological effects seem related to the setting in which the drug is taken”(Merck Manual, 1972). One even noted “an occasional panic reaction has occurred, particularly in naive users, but these have become unusual as the culture has gained increasing familiarity with the drug” (Merck Manual, 1982). Another noted that cannabis’s effects are dependant upon “the dose of the drug and the underlying psychological conditions of the user” (Taber, 1997).

Unfortunately, the prohibition of cannabis had a negative effect on its medicinal reputation. Textbooks began to remark upon the “completely unpredictable” (Faddis, 1943) nature of the drug, or it’s “unreliability” (Dilling, 1933, Merck Index, 1952) in providing consistent results – blaming the drug itself for the researcher’s own inability to understand the proper cultivation of cannabis for medicine, the various strains/cannabinoids and their various effects or the importance of the subject’s mindset and setting. Some textbooks then began omitting entirely any mention of cannabis in their later additions (Pierce, 1935, Blumgarten, 1940). Others began to blame whole-plant cannabis for the effects experienced by one of it’s isolated cannabinoids (Martindale, 1977, Carter, 2008).

Still, the special relationship between cannabis’s prohibition and its reputation was accurately assessed in the 1987 Merck Manual: “…the chief opposition to the drug rests on a moral and political, and not a toxicological, foundation.”

Post Script:

These rough copies eventually turned into these good copies: